Decades of persecution of the Rohingya community in Myanmar have culminated in large waves of forced displacement, and a total of nearly one million now live as refugees in the camps of Cox’s Bazar across the Bangladesh border. Many others have sought refuge in Malaysia and other countries across the region.

Seeking mobility to flee violence and persecution has been predominantly a life-saving necessity, and sometimes it is also an attempt to secure better long-term prospects and security. But the prospect of transnational mobility gives rise to a tapestry of risks: people sometimes suffer sexual violence, starve, or drown during boat journeys. Despite these risks, some Rohingya people continue to pursue transnational mobility in an effort to improve their own lives and those of their families.

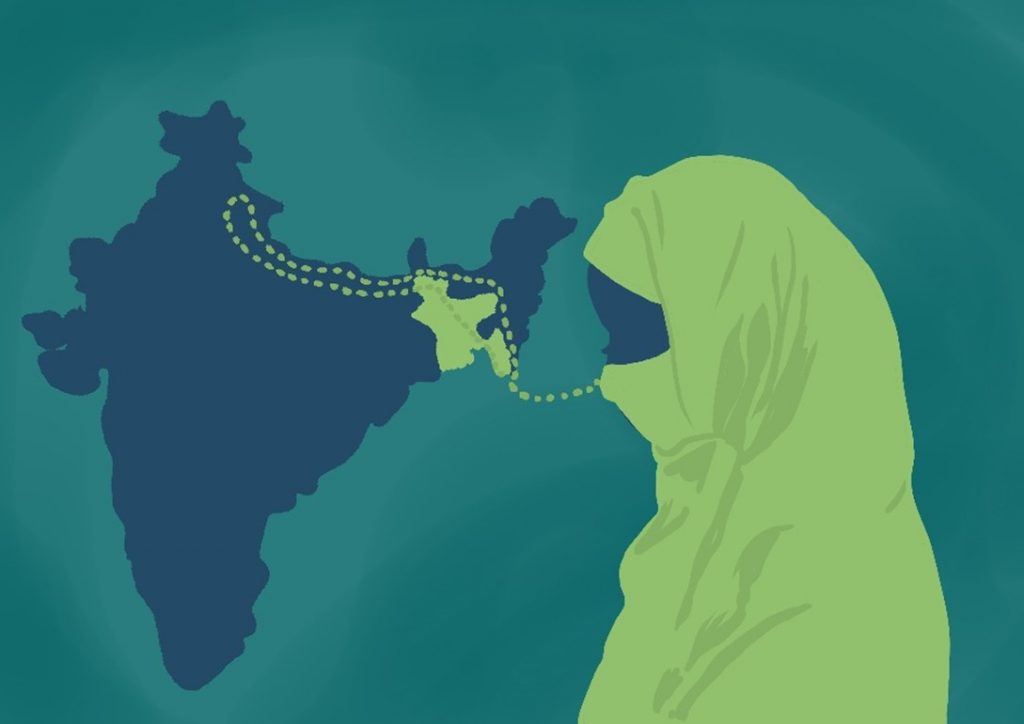

In 2019–2020, researchers from the Centre for Peace and Justice (CPJ), Brac University held interviews with residents of the refugee camps encouraging them to share their family’s stories. These interviews have now been written into narratives, taking into account sensitivities and security. Names and other identifying details have been changed or omitted where appropriate to protect respondents. Accompanying the narratives are illustrations of emerging themes interpreted by a Bangladeshi artist and are not meant to represent accurate depictions of the situation.

The result of these interviews is a rich collection of multigenerational oral histories that shed light on each family’s unique and personal circumstances. As a Rohingya learner who is a participant in a CPJ training course notes, “Life is not easy to survive without freedom, wherever you go but maintaining your identity is very important.” These visual storytelling narratives aim to amplify the voices of these Rohingya people while bringing awareness to their plight. To read the full narratives, visit https://rohingyastories.org/

A Refugee Child Labours to Achieve His Goals

As a kid, Amin provided labor services in the camp. He started as a porter carrying firewood and food rations, earning about 0.01 USD per load. On some nights he would attend a private learning center and study until the morning. To earn more, he found work at a tea stall and later applied as a volunteer with an NGO. He was able to pay tuition with his new job. At the time, few Rohingya refugee students reached secondary school. Through a friend who noticed his academic talent, he came to Cox’s Bazar to take admission exams and was admitted at a high school. He studied there for three years. When he received his high school exam results, Amin was overjoyed to learn that he had passed. He obtained admission to a technical college but began dreaming of attending a university.

“As a kid, I would go to early morning madrassa classes, then to a private tutor to study until later in the morning. After that I would go to NGO offices looking for loads to carry. It was a slow and hard way to make money.“

His study time was often compromised by the need to continue working full-time as an NGO teacher to help support his family. Good luck occurred when, two months before his final graduating exams, there was a protest in the camp by all the teachers – a strike to demand higher salaries. This gave Amin two free months to study without the option to work. After graduating from technical college, he managed to get admission to a university in Bangladesh, where he now studies.

Providing Remittances from Jammu Kashmir

“In 2012, some Rohingya girls were raped by the Tatmadaw,” Asma says. At the age of 13 Asma was sent to India by her family as the situation in Myanmar was getting worse and her family did not have enough money to pay for a dowry for a good marriage in Myanmar. She first traveled to Bangladesh and through a trafficker continued her travels to India with a group of migrants. Once they arrived by train in Jammu Kashmir, she was connected with a Rohingya family.

Asma stayed with the family for a month until her marriage was arranged. Her husband who is eight years her senior, worked as a cleaner at a cinema. During the time, Asma and her husband sent remittances to his siblings as well as to Asma’s parents in Myanmar, relying on the services of a hundi. In 2018 she and her husband decided to come to Bangladesh, mainly to be closer to their families. Asma says that she and her husband think it best to stay in the camps for now, and are awaiting the day when they can repatriate to Myanmar.

Willful Imprisonment as a Strategy to Reunite

Hirul worked with an international NGO in Northern Rakhine State after graduating with an LLB degree. After resigning from the NGO he left his wife and two young children to migrate to Saudi Arabia. Hirul’s intention was to save up some money for a few years, then arrange for his family to come to Bangladesh and help them get established there. He thought this would be a way for his family to live safely and happily. He sent a portion of his earnings to his wife every two or three months. In 2015, when the NLD came into power, like people all over Myanmar and the world, Hirul was hopeful that Myanmar would progress into a more peaceful era. He flew to Bangladesh, where he spent ten days before being arrested when he crossed the border back into Myanmar.

“I talked with a friend who advised me that yes, six months is ok, because after that I would be able to live peacefully with my family. So I came.”

Without explanation, Hirul learned one day that his sentence had been extended from six months to five years. He was released in late 2019 after serving three years of a five-year sentence. Hirul did not find crossing the border too difficult or dangerous, but it was expensive. On the day he arrived in the refugee camp his son came to meet him in the market and showed him the way to the family’s tarpaulin shelter. “I didn’t recognize him,” Hirul remarks. “He was six when I left and he is 16 now.”

A Young Teacher Flees to India, then Bangladesh

Showrife is a 25-year-old young man born in northern Rakhine State during a time of political tensions in the early 1990s. His father was killed by Myanmar security forces when Showrife was two years old after being detained along with four relatives. Showrife’s mother was left to raise three boys on her own, and tried hard to educate them despite not having much access to income. Showrife and his two brothers were raised in part by their mother’s father, whom everyone calls Nana, an affectionate term for grandfather in the Rohingya language.

Showrife first fled to India as a teenager in 2012. He says he missed Nana and his other family members terribly and cried a lot during those days. Fortunately, he reached Jammu Kashmir, where he stayed with his brother, who helped him. Although he grew professionally in India working as an interpreter, in 2018 he traveled to Bangladesh and reunited with Nana and his mother, who had become refugees in Cox’s Bazar. Nana, now 72 and a fluent English speaker, says he is the only Rohingya medical doctor living in the camps. He was a government servant, a Myanmar citizen.

Showrife says Nana “taught us discipline. In life, you only have a few people who really show you how to live, who really guide you. Nana was that for me.”

Remittances, Education, and Fulfilling Family Duties

Yassir hails from a family of seven sons and two daughters. Two of Yassir’s brothers are in Malaysia and one sister remains in Myanmar. The rest of the family live in the camps, and depend partially on remittances sent by the brothers in Malaysia. Yassir’s two brothers in Malaysia each earn about 2,000 Malaysian ringgit per month (480 USD), one as a construction captain, and one as a worker in a teashop. The brothers’ cost of living in Malaysia is about 1,000 ringgit per month and they send the rest to their parents and siblings in the camps. Yassir says they do this gladly, knowing that their contribution supports the many members of the large family.

Of the two brothers in Malaysia, the elder went to Malaysia in 2012 by flight. The younger brother followed him in 2015, traveling by boat. After sailing five days to Thailand, he then traveled to Malaysia by land. Upon arriving at the Thailand-Malaysia border, Yassir’s family had to pay 1,500,000 Myanmar kyats (1,140 USD) to a trafficker before crossing. Yassir recalls how worried his family was during his brother’s journey, as they didn’t have any contact with him. Fortunately, he arrived safely.