Six and a half years ago, the self-proclaimed Islamic State (IS), also known as Daesh, was driven out of Mosul. Under the terrorist group’s control, the city and its identity was attacked. In pursuit of their extreme version of Salafism and the creation of a caliphate, IS killed friends, families, neighbours, and broke up communities. The group committed urbicide, destroying important cultural heritage sites in an attempt to extinguish the cosmopolitan spirit of the city. Thousands were forced to flee their homes during the three years of this violent regime.

IS aimed to erase the Mosul that so many knew, loved, and identified with, but if you were to visit the city now, you would see that it’s beginning to recover. Spearheaded by both local and international initiatives, rebuilding efforts are underway. And, while they work hard on clearing the rubble and restoring the built environment, Mosul’s citizens are dealing with the psychological and emotional scars of the conflict. Because post-conflict reconstruction is not just a case of laying bricks. It’s about laying the ground for reconciliation.

Al-Nabi Jarjis Shrine and Mosque. Credit: Craig Larkin

Old souks in Mosul. Credit: Craig Larkin

I travelled to Iraq in May 2023 with my colleagues on the XCEPT research programme, Dr Craig Larkin and Dr Rajan Basra, to see how communities in and around Mosul, and the wider province of Nineveh are trying to move forward after the conflict.

The purpose of our trip was to learn more about the work being done as part of the reconstruction process, and to better understand the hurdles that stand in the way of post-conflict recovery.

Dr Inna Rudolf, photographer Ali al-Baroodi, and Dr Craig Larkin by a statue celebrating the role of locals in rebuilding Mosul after its liberation. Credit: Inna Rudolf

Our research began in Baghdad, where we met with officials from the Iraqi Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Ministry of Culture. We had noted a considerable increase in the Iraqi government’s dedication to expediting the reconstruction and stabilisation process in Nineveh, and we were keen to understand the ministers’ perspectives on the role of culture in facilitating recovery.

Dr Inna Rudolf and Dr Craig Larkin at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Credit: Inna Rudolf

Although there was widespread acknowledgment among government officials of the importance of culture, we discovered that there was still a lack of coordination in developing an approach that integrated culture and heritage promotion with measures that tangibly improved people’s living conditions.

We left Baghdad with assurances from decision-makers that they would continue to accelerate reconstruction efforts. Keen to assess if local communities were genuinely regaining trust in the government’s commitment to improve their livelihoods, we made our way to the city of Erbil.

From Erbil, we embarked on trips to the cities and towns of Mosul, Bartella, Sinjar, Lalish, and Sheikhan. Despite being well-acquainted with the latest updates on Mosul’s reconstruction process, witnessing the city in person still profoundly affected me. Under IS, 47 architectural sites had been deliberately demolished, and following the group’s rule and the battle for Mosul’s liberation in 2017, 80 percent of the Old City had been destroyed.[i] The sheer extent of destruction and the countless damaged buildings reduced to rubble were stark reminders of the immense challenges still facing the city’s residents.

A destroyed building in Mosul. Credit: Rajan Basra

While in Mosul, we had the pleasure of being taken on a guided tour of the city’s cultural landmarks by my friend and famous Moslawi photographer, Ali Baroodi. He not only showed us the emblematic Al-Nouri Mosque, but he also took us around Al-Tahira Church, Al-Saat Church, and revealed some hidden jewels of the enchanting old Bazaar.

While enjoying a cup of traditional Moslawi coffee at one of the city’s ancient breweries, Ali told us about the historic importance of the old storage houses, where Moslawis used to store wheat and provisions for darker days. Having experienced notables or pashas – a form of notable – taking away the crops they had harvested, the city’s residents had learned the hard way to always have something hidden away for bad times. Ironically, as Ali playfully remarked, these anecdotes, when divorced from their historical context, have contributed to the misleading stereotype of Moslawis as being frugal. Delving into the true background of their unique self-preservation instincts, and unwavering determination to assert their rights and survival throughout history, was truly captivating.

The interior of Al-Tahira church. Credit: Rajan Basra

The old Bazaar. Credit: Inna Rudolf.

Al-Nouri Mosque. Credit: Inna Rudolf

We also visited the University of Mosul’s Central Library. In the collective consciousness of Moslawis, the library remains one of the most important cultural institutions in Iraq, with a collection of over one million books and historic manuscripts. Despite the extensive damage inflicted by IS, UNESCO, working in partnership with the Iraqi Ministry of Culture and local communities, was able to restore the library to its former glory, which included salvaging many damaged books and manuscripts. Although the design of the reconstructed building focused on preserving its architectural heritage, modern features and technologies were also included to meet community needs.

Some signs of damage on the walls of Mosul’s library have been purposefully left intact. As the Iraqi historian Omar Mohammed argued, these scars were left both to remind people of what had happened, and to help them move on with their lives: ‘We need to use this tool to help the people heal the trauma they have been living, to help them ease the shock they have gone through and the very troubling experience of Daesh.’

Alongside the reconstruction of the built environment, my colleagues and I were interested in tracing the recovery of the city’s unique spirit. We’d chosen to focus our peacebuilding and recovery research on Nineveh because of its vibrant social fabric, and because of the symbolic significance Mosul has historically embodied as a beacon of cosmopolitanism.

I’ve frequently travelled to different parts of Iraq over the last seven years to carry out fieldwork, but this was the first time I was able to interview local practitioners and community leaders on the ground, who are working hard at the grassroots level to help the city move forward.

We had the privilege of meeting the remarkable team at Volunteer With Us, an organisation that epitomises the power of collective action in rebuilding the city and transforming the lives of its residents. In the aftermath of the conflict, their campaigns rallied people together, united in their mission to clear neighbourhoods of debris and wreckage. Over time, the organisation has shifted its focus to work closely with schools, raising awareness about vital environmental policies, nature preservation, and the promotion of culture.

Ahmed Mohammed, founder of Volunteer with Us, Dr Rajan Basra, Dr Craig Larkin, Ayoub Thanoon from Mosul Heritage House, and Dr Inna Rudolf at the Volunteer with Us headquarters. Credit: Inna Rudolf

Their headquarters, nestled within the grounds of a lovingly reconstructed historic house proudly bear a banner that reads ‘Volunteer with Us!’ The building serves as a testament to their commitment to preserving the past while invigorating the present, creating a space that beckons locals and visitors alike.

Volunteer with Us. Credit: Inna Rudolf

This harmonious fusion amplifies the power of heritage, fostering a sense of collective engagement and inviting diverse individuals to contribute their time and skills. In an interview with us, the founder, Omar Mohammed, connected his vision for the initiative to the Moslawis’ responsibility to live up to the heroism of their legendary ancestors:

Our history can be traced back to numerous civilisations, kings and empires such as the Ancient Assyrian Empire, Sumerian civilisation, and Hammurabi who was the king of the old Babylonian Empire. Our achievements paused during the recent years. Today, Iraqis want to realise numerous achievements and victories. We, as youth, want to leave a positive mark on our contemporary history. Through our work we hope to send a message of peace and strength. It is crucial for Iraqis to recognise their impressive past and history, which will motivate them to continue this legacy and strive to help our country.’

Witnessing the volunteers’ unwavering dedication underscored the invaluable role of grassroots efforts in fostering positive change and renewal within the city. It’s important to make sure that such initiatives have access to funding resources comparable to those available to larger and more prominent organisations. Championing these lesser known, but impactful, ventures will help foster a diverse and inclusive landscape of support, propelling positive change and transformation throughout society.

Volunteer with Us logo. Credit: Rajan Basra.

At Mosul Heritage House, my colleagues and I were shown around by Ayoub Thanoon, the founder of the Mosul Heritage project. This old house, which was partially destroyed during the conflict with IS, was restored with particular attention given to preserving aspects of the house’s traditional Moslawi architecture. The house is now rented by the Mosul Heritage project, who have turned it into a museum, and who use it as a base for cultural events, forums, and seminars, which draw visitors from across Iraq.

During our visit, Ayoub showed us around the different sections of the house. The first section includes several rooms with interiors replicating conventional Moslawi living spaces such as a traditional saloon, in which the household members would gather for coffee or receive guests.

Mosul Heritage House. Credit: Inna Rudolf

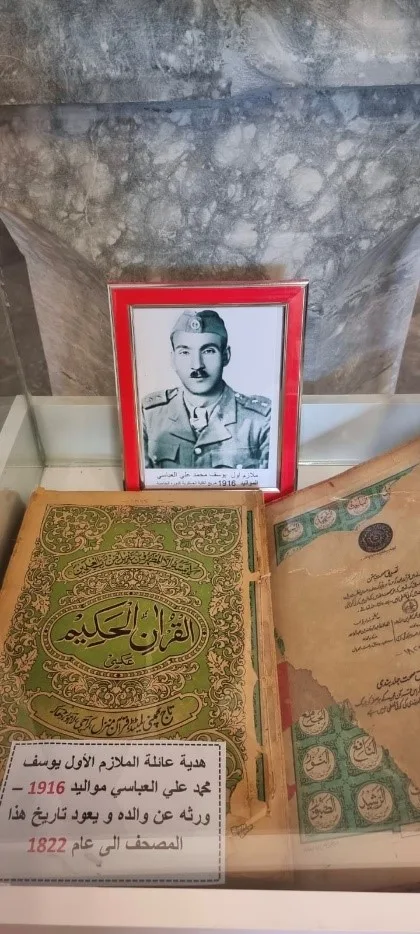

The second section is dedicated to the community centre which aims to inform visitors about UNESCO’s ‘Revive the Spirit of Mosul’ project.’ The third section hosts an impressive heritage museum with lovingly collected artefacts from different epochs of the city’s history, such as old sewing machines, record players, and newspapers and banknotes dating back to Iraq’s short-lived monarchy period.

Mosul Heritage House. Credit: Inna Rudolf

Ayoub hopes that, as well as rescuing and preserving Mosul’s identity, the museum will educate Moslawi youth about the history of their city. The organisation has now expanded its activities across the Nineveh governate, organising study trips and excursions which connect different communities and contribute to the development of a shared pride in the governorate’s heritage.

Ayoub Thanoon and Inna Rudolf at Mosul Heritage House. Credit: Inna Rudolf

The holistic approach adopted by Mosul Heritage Organisation serves as a model of people-centred heritage promotion and preservation initiative that has a real capacity to improve locals’ livelihood prospects, through its success in attracting tourists, while contributing to the emotional recovery and social reconciliation of conflict-affected communities across the province.

A similarly impactful, community-driven initiative was launched in 2019 by the talented journalist and cultural entrepreneur Saker al-Zakariya. Founding the Baytna (Our Home) Institution for Culture, Heritage and Arts, Saker sought to showcase the healing power of Mosul’s rich cosmopolitan legacy. Designed by Saker as a ‘place that deals with the Moslawi identity’, Baytna’s headquarters can be found in a 100-year-old traditional house, painstakingly restored with meticulous care and dedication, in the heart of Mosul’s Old City.

Intended to help rekindle the pride of Mosul’s residents in the unique heritage of their city, the walls of the museum house are decorated with portraits of famous local artists, writers, public figures, and even internationally renowned celebrities, such as star architect Zaha Hadid, who have left a mark in the collective consciousness of Iraqis.

Portraits of public figures adorn the wall of Baytna. Credit: Inna Rudolf

Displaying the generous donations from some of the city’s residents, an artfully curated collection of vintage items is delicately arranged on shelves crafted from aged driftwood, offering visitors a glimpse into the daily life of a bygone era, stretching back a century prior to the recent conflicts. Visitors are also invited to immerse themselves in Mosul’s Ottoman and monarchical past by adorning themselves in traditional costumes and wool fez hats.

Completing the time travel experience, on the rooftop, dressed in traditional attire, members of the Baytna team serve visitors authentic beverages and refreshments, while sharing entertaining stories about various stages of the heritage house project. It comes as no surprise that Baytna is a preferred spot for an array of cultural events such as public readings, concerts, and art exhibitions.

While Baytna can be read as a heartfelt declaration of the founder’s love for his city, this passion stems from his personal journey of coming to terms with Mosul’s violent history:

‘Since 2005, the city of Mosul meant nothing to me. I hated, loathed, detested it. I lost so many friends in the city. I tried to stay away from it. The night of its downfall in 2014, I cried hysterically until the morning because I felt for the first time I belong to the city, but at the same time I had lost the city. When Mosul fell, I started to feel a sense of belonging to Mosul. I began to identify myself as a Moslawi.’

Realising what was at stake upon witnessing the destruction of the city’s cultural heritage, Saker embarked on the mission of restoring his own nostalgic version of Mosul as the city which he remembers from the time before 2005, when armed Islamist groups such as al-Qaeda had started to undo the unique diversity of its social fabric:

’This foundation is mainly engaged in preserving and maintaining our heritage, our identity in Mosul … This foundation became an emblem to revive the city of Mosul. The French President demanded to visit us at the foundation during his trip to Mosul. More than 400 tourists came to visit us last year, ambassadors, the Iraqi prime minister – they all came to visit us.’

Saker takes immense pride in resurrecting fragments of the city’s glorious legacy and helping dispel the stigma haunting its residents. Oftentimes, their victimhood and identity are misunderstood by their fellow citizens.

For instance, Mosul has been known as the ‘city of a million officers’ due to the significant representation of Moslawis in the army during Saddam Hussein’s regime.[i] Unfortunately, this has led to unfair prejudices, with Moslawis being unjustly labelled as supporters of the Baath party – the party which brought Hussein to power and allowed him to rule as a dictator in Iraq for over three decades. Such sweeping generalisations fail to recognize the historical context: the military career ingrained in the identity of Moslawi communities dates back to Ottoman times when the city hosted essential military barracks, and this history of military service has continued throughout the centuries, regardless of which regime held power.

Saker’s efforts not only preserve the city’s history but also challenge misconceptions, allowing for a more nuanced understanding of Mosul’s past and its people. By shedding light on the rich heritage and traditions of Moslawis, Saker aims to bridge the gap of misunderstanding, fostering greater unity and appreciation among different communities.

Baytna. Credit: Inna Rudolf

In a sense, both Ayoub’s and Saker’s personal fascination with the city’s cultural heritage, and their commitment to restoring Mosul to its former glory, represents their longing for a more distant past, uncontaminated by sectarian identities. This is not escapism, but rather a desire to give hope to Mosul’s traumatised youth, to help them restore their pride in the city, and to help them move beyond the divides that IS tried to sow. Because there are still rifts that need healing. It may have been six years since Mosul was controlled by IS, but there are still an estimated 100,000 Moslawis who have chosen not to return home, or who have been unable to.

During our time in Iraq, we also looked more broadly at the role of different ethnic and religious minorities. In Sinjar, we visited the House of Co-existence in Sununi, headed by the famous human rights activist Mirza Dinnayi.

House of Co-existence. Credit: Inna Rudolf

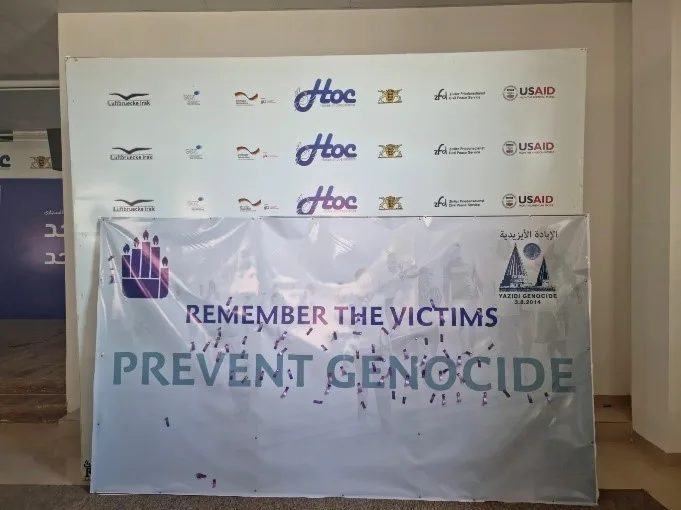

We also had the opportunity to visit the Yazidi temple in Lalish and partake in a cultural festival in Sheikhan. The Yazidi people are an ethno-religious minority group who were largely based in the Sinjar region in northern Iraq, and who suffered severe atrocities at the hands of IS. On 3 August 2014, IS invaded the Yazidi heartland and, in the space of two weeks, killed over 5,000 men, enslaved thousands of women and children, and caused the displacement of hundreds of thousands. Today, thousands of Yazidis are still missing, and an estimated 200,000 remain displaced.[i] Engaging with the elders during these encounters, we gained insight into the numerous challenges they confront due to their religious beliefs, hindering them from fully experiencing a sense of equal citizenship in Iraq. For example, we learned about instances where representatives of other religious communities would decline Yazidi-prepared food, as they deemed it ‘impure’. These experiences emphasised the importance of addressing religious tolerance and promoting inclusive coexistence to foster a harmonious society.

The town of Sheikhan. Credit: Imad Qusay Abbas

We gathered valuable insights into the tensions prevalent in Nineveh, particularly concerning the Turkmen from Tal Afar, specifically Sunni Turkmen, who bear the burden of being stigmatised for their perceived support of IS. Historical accusations against Turkmen from the outskirts of Mosul, particularly those from Tal Afar, have also labelled them as overly eager to climb the social ladder and align themselves with unjust causes and regimes to enhance their social mobility.

These perceptions can be traced back to the purported / reported conduct of some Sunni Turkmen during the Baath party regime under Saddam Hussein. Consequently, some local Sunni Arabs in Mosul tend to hold Turkmen responsible for the stigma associated with Moslawis as supposed IS supporters or Baathists.

Dr Inna Rudolf at the Yazidi temple in Lalish. Credit: Imad Qusay Abbas.

In Nineveh, due to the involvement of certain Sunni Arabs with IS, there are individuals who tend to generalise Sunni Arab Moslawis as a community that condoned or tolerated the extremist group. The Sunni Arab Moslawis, however, strongly reject this assertion. The complexity of these dynamics emphasises the need to address historical grievances and correct misperceptions in order to foster mutual understanding and reconciliation within the diverse communities of Nineveh. Hence, the renowned initiative Mosul Eye, founded by the prominent historian Omar Mohammed, has undertaken a noteworthy endeavour, collecting oral histories and testimonies from different communities throughout the Nineveh region. These accounts serve to both preserve collective memories of the past and illuminate aspirations for the future.

The initiatives we saw in Mosul go far beyond the obvious contribution to restoring the city’s built heritage. They have an undeniable impact on locals’ emotional and psychological healing. These initiatives should not be evaluated primarily against the background of the ‘authenticity’ of the rebuilt structure, but should instead be measured by their ability to influence local communities’ feelings of pride and belonging to their built and social environment.

Ali al-Baroodi, Dr Inna Rudolf, and Dr Craig Larkin in Mosul. Credit: Rajan Basra.

For Mosul, for Nineveh, and for Iraq to move forward, trust in the state needs to be restored. To achieve effective post-conflict stabilisation, it is crucial for the Iraqi government to be perceived as the driving force behind both economic and cultural recovery. This entails the international community occasionally taking a back seat and refraining from seeking credit and visibility for its substantial contributions. By empowering and urging the Iraqi government to provide adequate support to the burgeoning civil society scene, the international community can better facilitate the nation’s journey towards sustainable progress and self-determination.

The international community can also do better in supporting the efforts of local actors, those working hard on the ground to rebuild their own communities.

Reconstruction in the Old City of Mosul. Credit: Rajan Basra.

Furthermore, the Iraqi state faces the critical task of addressing the fate of internally displaced people. For those who wish to return to their homes, the government must establish sustainable measures to ensure their safe and supported reintegration. At the same time, as some individuals are in the process of establishing new lives in different locations, it is vital for both the Iraqi government and international organisations to actively cultivate a sense of belonging to the state. Measures should be taken to facilitate meaningful connections between these ’newcomers’ and other communities affected by the conflict. Collaborative efforts in these domains are crucial to lay the foundation for a more cohesive and harmonious society.

One thing my colleagues and I left Mosul with was a great sense of responsibility towards all the people that opened their homes and their hearts to us, and who shared with us their dreams, fears, and their experiences.

It is important to make sure that their stories, and their perceptions of conflict and post-conflict realities, are heard and reported accurately so that decision makers and donor organisations can understand the challenges different communities face and what they can do to better support them.

Mosul may bear a history of conflict, but it also boasts a legacy of coexistence and a remarkable resilience, akin to the mythical phoenix rising from the ashes. It is precisely this enduring spirit that local champions are striving to revive and reclaim.

Statue celebrating the role of locals in rebuilding Mosul after its liberation. Credit: Inna Rudolf

This XCEPT blog was originally published by King’s College London on the International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation website.

You can read more about the findings from this XCEPT research in the recently-published journal article, Iraqi heritage restoration, grassroots interventions and post-conflict recovery: reflections from Mosul.

[i] https://www.newarab.com/news/iraq-announces-return-487-yazidis-sinjar

[i] Interviews with Iraqi practitioners, 2022

[i] Monuments of Mosul in Danger project. Accessed at: http://www.monumentsofmosul.com/index_htm_files/Monuments%20of%20Mosul%20in%20Danger.pdf