Dr Omar Mohammed is a renowned historian and the voice behind ‘Mosul Eye’, a blog which anonymously documented life under Islamic State (IS) in the city of Mosul, Iraq. Today, the Mosul Eye Association focuses on promoting the recovery of Mosul and its cultural heritage, as well as empowering the city’s youth. The most important task Mosul Eye is undertaking is to promote Mosul globally to replace the negative image of the city after its fall to IS in 2014 and the subsequent destruction.

Hi Omar. Thanks for joining us. Please could you explain what Green Mosul is?

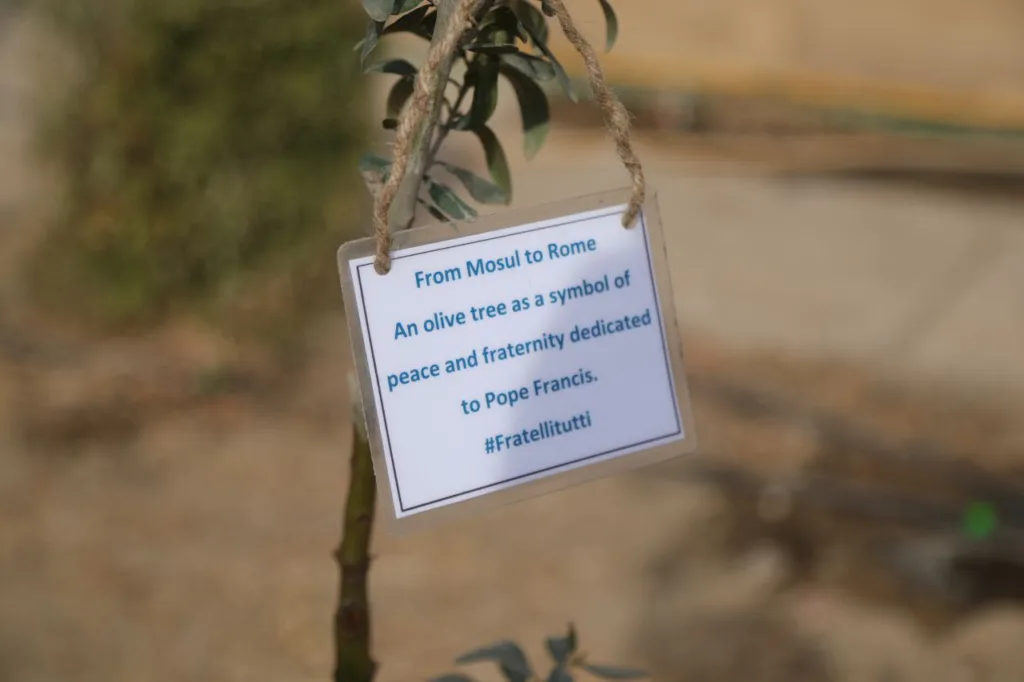

Green Mosul was an initiative started by Mosul Eye, and ultimately led by youth, to plant trees in the city of Mosul, but really it has two definitions. It refers to the greening initiative, which was the effort to repopulate Mosul with green space after the massive estruction that took place during the conflict. But it really aimed at, and can be defined as, an initiative to support reconciliation in post-war Mosul.

Following the conflict, there was a need to bring the people together, and to do that we needed to find something everyone could relate to. We wanted to disconnect them for a short time from the religious and social problems in the city, and we settled on one thing they could agree on: a tree. A tree doesn’t have a religion. It doesn’t have an ethnicity. It only has what benefits the community: clear, clean oxygen, a good view, and the ability to create a nice landscape.

Green Mosul ran from March 2022 to March 2023, and, in that time, we planted 9,000 trees in Mosul and the wider Nineveh province. When we started the initiative, we signed agreements with the local government and with the universities, and one of the terms was that they would commit to planting trees every year. Green Mosul has now technically ended, but the University of Mosul and the Technical University of Mosul continue to plant trees on an annual basis, and the local government has also dedicated a portion of the budget to planting trees every year. Our initiative didn’t stop when we finished our work. We wanted to make sure that it continued and that others could build on it.

Was it easy to get the support you needed to launch Green Mosul? How was the idea first received?

At the very beginning, we sought the support of the Iraqi government, but they wanted to see results before they got involved. I then approached the French government, as I knew they were interested in such initiatives. Their cultural attaché liked the idea, so I went away and developed the initiative amongst the community. One month later, the French government approved the idea, and Green Mosul was borne. Once we’d secured the funds, the local authorities were keen to support us, and we signed agreements with the forestry department, the municipality, the universities, and with other entities in the city. It became a fully Mosuli initiative, where the people and the government were working together for a common interest: the urban greening and, at the same time, the rehabilitation of the social fabric of the city.

Was it important for you to have the local authorities involved?

It was. One of the hurdles to post-conflict recovery in Iraq is that many people see the authorities as dysfunctional. I might agree with them, but I see that there is a way of utilising this dysfunctional government by making it functional – and the only way to make it functional is when you involve them. So Mosul Eye brought the Green Mosul initiative to the government, and they helped make it happen. We didn’t have cars to transport the trees, so we used the municipality’s cars. We didn’t have the ability to create the irrigation system for the trees we were planting, so we used the forestry department. I think their involvement also helped the initiative grow. Members of the public are not necessarily aware of what ‘social cohesion’ is, but they saw Green Mosul as a reliable initiative because of how many people were involved.

Through Green Mosul, we were also aiming to create trust between the authorities and the population. We wanted it to be a collective effort, because the initiative also focused on a very important principle, which is that the process of healing has to be collective in order for it to be strong and impactful. Mosul Eye helped the government to understand the critical importance of social cohesion and of rehabilitating the social fabric, but at the same time, the government gave us the equipment and the space. I think we contributed collectively, and that’s why I always say that this is an initiative of Mosul – it’s not just an initiative of Mosul Eye. It’s important to show the people that they have agency in the process of their healing. They need to own it.

What was the response like among the local community? Were people keen to get involved?

We had a specific communication strategy when we first approached the local communities. We made sure to keep the same distance with the community leaders and the public, because we didn’t want to create the impression that Green Mosul was only for elites. So we spoke to the Yazidis, to the Christians, to the Shia, to the Sunni, and to the endowment administrations of the Yazidis, the Christians, the Shia, and the Sunni. We made sure that the first communication was with the public, and then we facilitated their own communication with their community leaders. Once the locals initiated the conversation, the community leaders came to us, and asked to get involved.

In fact, one of the places where we planted trees was as a result of communication with a woman from Tel Keppe. She told us there was an empty park in the city, and the community wanted to use it to create a space for their children, but the land was owned by the church. It wasn’t easy to convince the church at that time, and distrust between the different religious communities was still strong. We were trying to avoid being labelled religiously – we were trying to be seen only as individuals who had an interest in rehabilitating these spaces – so I spoke to the head of the church and explained that it was a great space. The church would probably receive more visitors if people came to the public park, and everyone would be happy. The priest agreed, and we created a public space where there was both a religious site and a secular site. Today, the same priest is asking me for more trees to be planted.

Within the communities, we also started receiving offers from people saying they didn’t just want trees to be planted in their space, but they wanted to contribute trees to be planted elsewhere. One person also suggested that we plant trees for those lost during the conflict, and then everyone started coming forward with names. They wanted to put the name of their son or daughter, or their mother or father, with this tree or this tree. In the first few months, it was Mosul Eye and the municipality running Green Mosul, and then it became led by the people themselves.

Were the sites where the trees were planted important, or was it more about the process of bringing different communities together?

The two things were intertwined. Some of the sites we chose were religious, because we wanted to try and encourage young Muslims to go to Sinjar and plant trees around the worshipping place of the Yazidis, for example, and young Yazidis to go to Bashiqa or to Mosul and plant trees inside al-Nouri mosque and Al-Saa’a church. We tried to treat these sites holistically, so we communicated to the people of those faiths that we had an interest in their religious space, but, at the same time, they were also heritage sites and public spaces for the people. We did the same in the Shia, the Sunni, the Christian, and the Yazidi majority areas, but there was one condition: that a Yazidi plants in a Muslim side and a Muslim plants in a Yazidi side and so on.

Green Mosul also planted trees in heritage sites, and we had an agreement with UNESCO, whose supervision those sites were under. We planted trees in their sites, but on the condition they would become part of the public space. We always tried to make sure that the planting of trees was seen as being outside the lens of religion – it was a holistic approach that involved everyone.

You mentioned distrust between religious communities earlier – was it difficult to persuade a person from one religion to plant trees at the religious site of another?

At the beginning, it was difficult, and sometimes we needed to have difficult conversations. But we also trained around 25 people from all communities to use as the face of the initiative. They would reach out to their communities, and they would explain that they were there wishing no harm, but they were there to contribute to the community. And when people saw the results – when they went to a place with no trees and when they went back and saw the trees planted – they understood. After a short time, things went smoothly.

When you started Green Mosul, what did you hope the outcome would be?

To be honest, when we started, I had fears it would not succeed. Given the gravity of what had happened in the city, I was concerned people might not be interested. But we started Green Mosul with three goals. One was that we would create a sense of responsibility among the people. Many had become disconnected from the city as a result of what had happened since 2003, and we wanted to reintroduce a sense of responsibility among citizens to contribute to their city. Our second aim was to introduce a mechanism of communication between communities that wasn’t about religion or ethnicity. The third was to create trust between the government and the public. I still make sure I communicate everything I do with the government, and then I communicate this to the public. I wanted to reintroduce the meaning of governance. I wanted the public to know the government is not just people sitting behind closed doors, but that they themselves can gain access to them and work with them.

We’ve achieved those three things, but we’ve also created friendships between different communities. They still visit each other, they are friends with each other, and they are still communicating. These different communities are working together, and that’s what we aimed to do, and we succeeded. I’m so happy about the results. I’m so happy about the involvement of the community. I’m so happy that we were able to do this in a complicated context, where people are still healing. This means there is potential for people to work together in Mosul to create a sustainable future for themselves, but it will take time.

The other element we introduced is that we raised awareness about climate change in a very complicated context – imagine talking about climate change in a city that is heavily destroyed and where people are still missing. But Green Mosul succeeded in introducing the conversation around climate change, and the university is now running research and attracting more researchers to work on the subject. One topic which is dear to me is what I call ‘green heritage’. I saw the impact of the destruction of cultural heritage on the people and the potential conflicts that it might create, and I realised that, although Islamic State might not come back, there is another enemy: climate change. It’s important to address this when we speak about preserving cultural heritage. The recovery of Mosul’s cultural heritage plays an important role in the collective healing from generational trauma, and it gives hope to the people that social cohesion is still possible as well as limiting the impact of radicalisation.

It sounds like Green Mosul has been a great success. How important do you think it is to have grassroots-led vs authority-led initiatives in Mosul?

I think encouraging the grassroots to lead more initiatives is fundamental for a healthy rehabilitation of Mosul, because not all recovery efforts succeed in meeting the results they intend. A quick rehabilitation might bring the opposite outcomes, so it’s important to create a sense of responsibility among the grassroots so they feel they have a say in what’s happening. Now is the right time to work on this, and invest in this, because we are still in the process of rebuilding and healing. It’s the best time frame we have to enable people to develop this sense of responsibility.

At the same time, we shouldn’t ignore the government. The government can always contribute, and opportunities can always be created if there’s a will, a sense of responsibility, and most importantly, diplomatic expertise – because it’s all about how you communicate your ideas in a post-conflict environment.

In Mosul, we need less focus on religion. When rehabilitation efforts target certain religious groups, they’re not talking about justice for all. They’re just reinforcing divisions. Create the space, and let people be the way they want. I think let’s talk more about trees than religion. You can plant trees in a mosque or in a church, but it doesn’t have to be because they’re a mosque or a church. It can be because you care about the environment or because you simply want to enjoy green space.

You can read more about XCEPT’s research on reconciliation initiatives in Iraq here: Iraqi heritage restoration, grassroots interventions and post-conflict recovery: reflections from Mosul