In recent years, high-resolution satellite imagery and geospatial analysis have become increasingly valuable tools in documenting the effects of conflict, including the widespread destruction of infrastructure, property, and lives in Ukraine, Gaza, and Sudan. In January, satellite imagery played a pivotal role in the U.S. Department of State’s determination that members of the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) and allied militias had committed genocide in their attacks against non-Arab communities in several locations in Sudan. Most recently it has been used to document the damage caused by missile and drone strikes in the ongoing India and Pakistan conflict.

Conducting research on sensitive or contentious issues in fragile and conflict-affected areas where demographic data is flawed, access to remote and insecure areas is challenging, and representative samples prove particularly elusive is a perennial problem. In these terrains, fieldwork is typically limited and skewed by security concerns and the associated costs, and it is often the voices of elites that are the loudest and most prominent. The Farsi phrase “Can hearing ever be like seeing?” reflects the greater weight that should be given to the things we can see for ourselves, compared to what we are told.

To this end, satellite imagery and informed analysis can be usefully deployed to study complex and sensitive issues in fragile and conflict-affected areas and support more effective policy development. While imagery is not a substitute for talking to the people directly impacted by conflict, our research on the outbreak of heavy fighting between Iran and Afghanistan in May 2023 shows that it is a critical tool in developing a better understanding of these complex terrains, where the loudest voices can dominate the media and social landscapes and skew research findings—and, all too often, policy outcomes.

Background to the Conflict

In May 2023, heavy fighting broke out between Iranian and Taliban forces on the border between Afghanistan and Iran. At the time, the media and many analysts looked to explain the incident as a result of the escalating “war of words” in the week before between senior officials in the Taliban and the Iranian Republic.

As is common during dry years, the Iranian authorities complained that Kabul had retained more than its fair share of water from the Helmand River, depriving farmers and communities across the border in the province of Sistan and Baluchistan in Iran. Under a treaty signed by the two nations in 1973, the water is a shared resource. The Iranian president at the time, Ebrahim Raisi, warned “the rulers of Afghanistan to give the water rights to the people of Sistan and Baluchestan,” prompting responses from senior Taliban officials.

Rather than focusing on the rhetoric surrounding the dispute, our research revealed novel insights into the conflict by focusing on concrete facts that could be observed through satellite imagery. Our research pointed to a more localized dispute about border management and the challenges of recalibrating cross-border relations following the collapse of the Afghan Republic and the subsequent Taliban takeover, and revealed far more pervasive issues with the widespread and unsustainable exploitation of groundwater across the Helmand River basin.

Disparities Between Observation and Discourse

The use of geospatial analysis in our research helped us better understand the accuracy of the competing narratives that authorities in Tehran and Kabul look to convey when complaining about transboundary water rights in the Helmand River Basin.

Typically, disputes between the two countries begin with the Iranian government accusing authorities in Kabul of withholding water from the Helmand River and failing to comply with their treaty obligations. Kabul authorities generally suggest the reduction in water flow is a function of drought, noting that there is a provision in the Helmand Treaty to reduce water flows under such conditions.

Tehran alleges that Afghanistan’s ability to store and divert water—through infrastructure projects such as the Kajaki Dam, constructed in the 1950s, and more recently the Kamal Khan Dam, built in 2021—has prevented sufficient water from being discharged into Iran for use by the population of Sistan and Baluchestan.

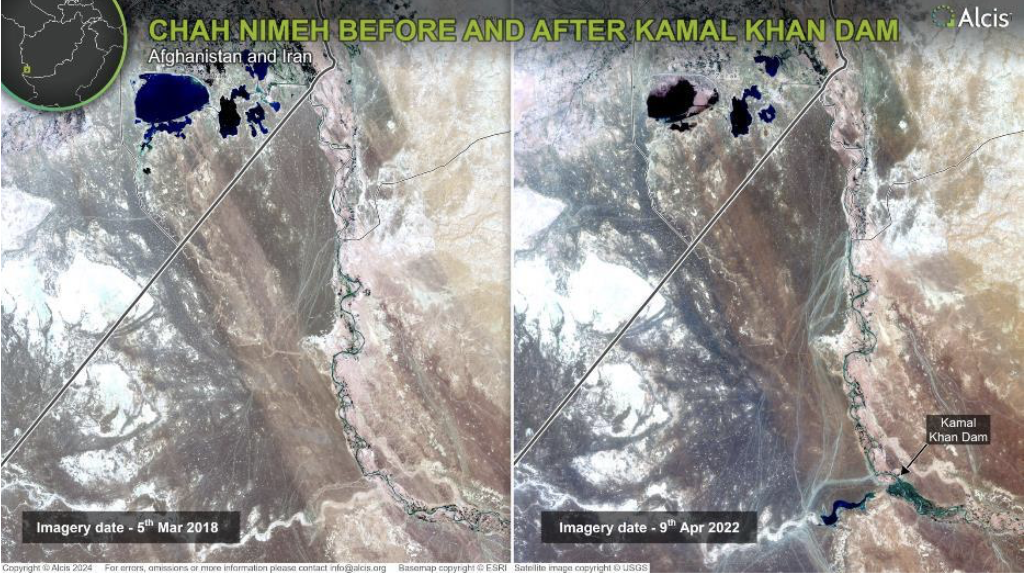

There is some truth to this complaint, especially since the completion of the Kamal Khan Dam. As satellite imagery has shown, this latest dam, constructed in the lower part of the Helmand River Basin—just upstream from the Helmand fork—now allows Kabul to release water from the Kajaki Dam in the upper basin to be used by communities downstream in Afghanistan while retaining any remaining discharge at Kamal Khan, and preventing it from flowing to Iran (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Chah Nimeh before (2018) and after (2022) the commissioning of Kamal Khan Dam. Copyright Alcis. Republished with permission (on file with Lawfare).

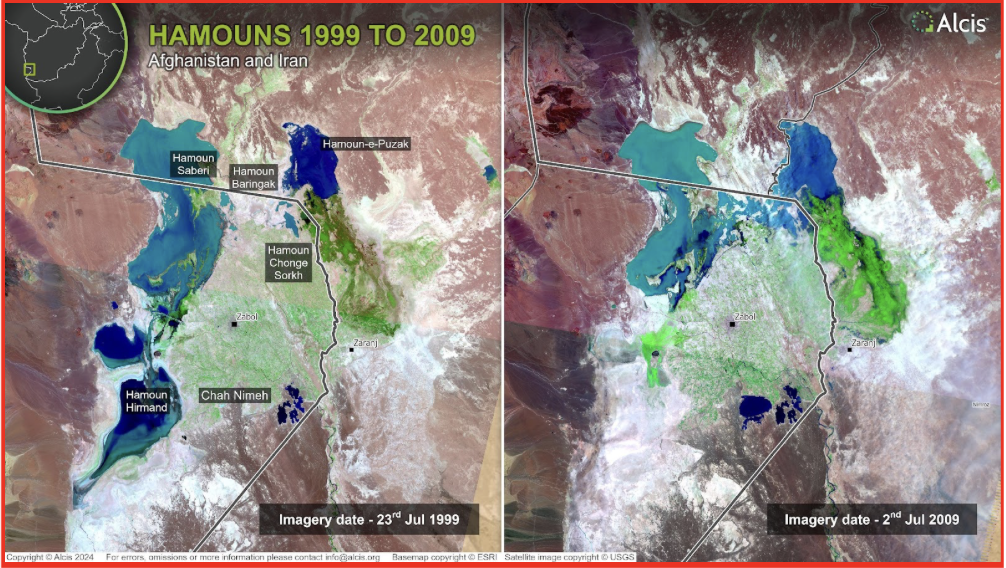

Further imagery analysis has shown that any efforts by the Afghan authorities to retain and divert water have been mirrored on the Iranian side of the border—often, some years earlier. For instance, the Jeriki Canal and Chah Nimeh reservoirs in Iran, located after the Helmand fork—where the Helmand River first meets the Iranian border—were initiated in the 1970s and 1980s, respectively, to divert and store water, mainly for the urban populations of Zabol and Zahedan. Before the construction of the Kamal Khan Dam in Afghanistan, these reservoirs captured the water once released from the Kajaki Dam. The construction of the Chah Nimeh 4 reservoir in Iran in 2008—which more than doubled storage capacity—subsequently significantly reduced the water flow into the Nad-e-Ali River and Hamoun-e-Puzhak in Afghanistan, and the Hamoun-e-Saberi in Iran (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Impact of construction of Chah Nimeh 4 on the hamouns. Copyright Alcis. Republished with permission (on file with Lawfare).

Consequently, while historically Tehran has argued that it is Kabul’s failure to release water from Kajaki that limited water flow to the hamouns—a series of terminal lakes and salt marshes—and Sistan and Baluchestan province, its own infrastructure efforts at the Helmand fork have been more detrimental to the rural livelihoods of the downstream populations in both Afghanistan and Iran. Indeed, Iranian authorities tend to prioritize the populations of Zabol and Zahedan; water is released from the Chah Nimeh reservoirs to farmers in Sistan and Baluchestan for irrigation only after the needs of the urban population have been met.

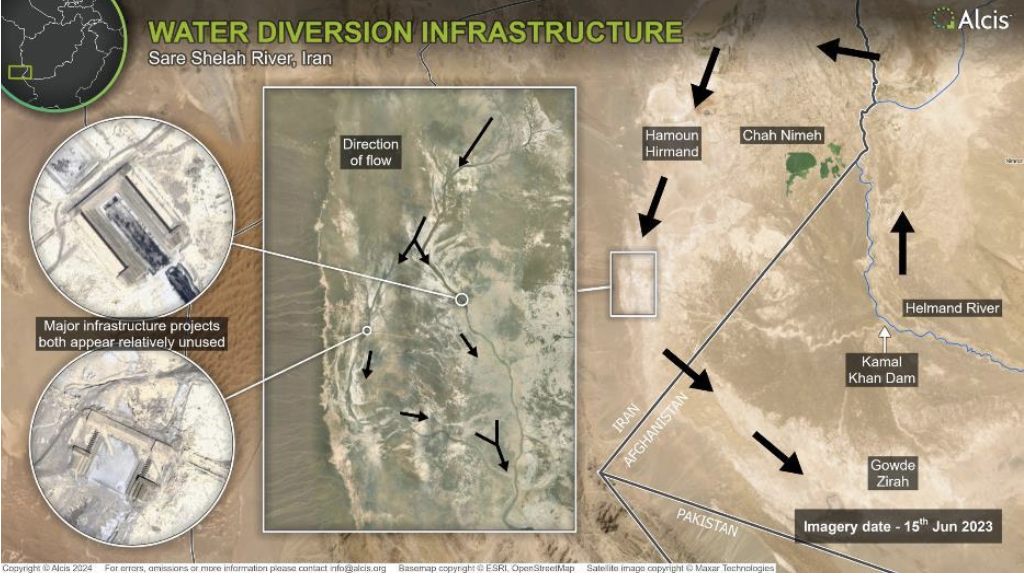

Through imagery analysis, it is also clear that Tehran sought to stem the flow of water from the Hamoun-e-Hirmand through a series of dams on the Sar-e-Shelah River in the district of Hamoun in Sistan and Baluchestan province (Figure 3). As such, while Tehran accuses Kabul of seeking to retain and divert water to its advantage and to the detriment of downstream populations in Iran, Tehran has been doing the same for longer and—until the completion of the Kamal Khan Dam—perhaps more effectively. While Tehran’s complaints have intensified since the completion of the Kamal Khan Dam, it is inaccurate for Tehran to portray itself as the sole victim and Kabul as the sole perpetrator.

Figure 3. Dams on Sar-e-Shelah River constructed circa 2001, redirecting water from flowing toward Gowd-e-Zirah. Copyright Alcis. Republished with permission (on file with Lawfare).

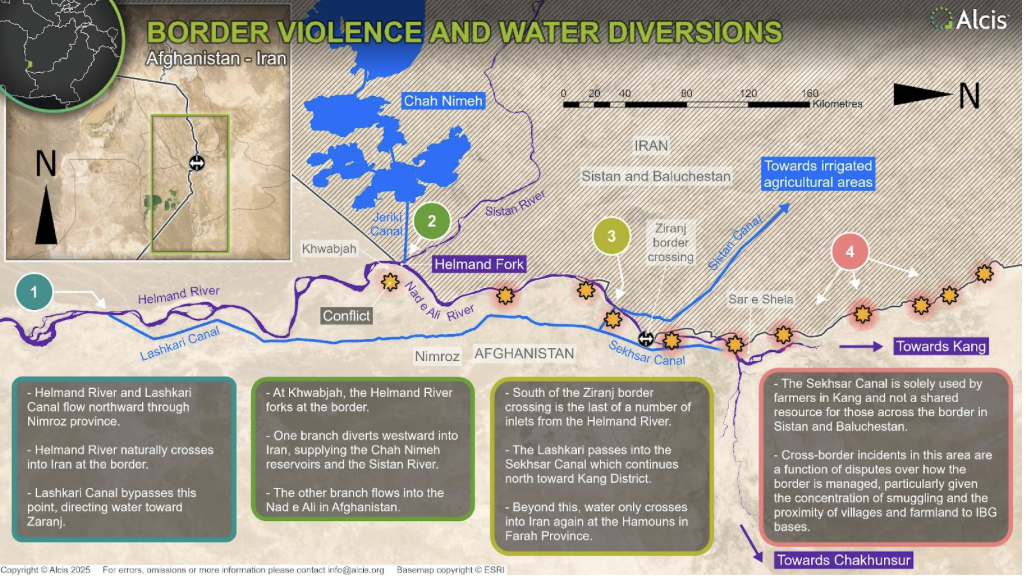

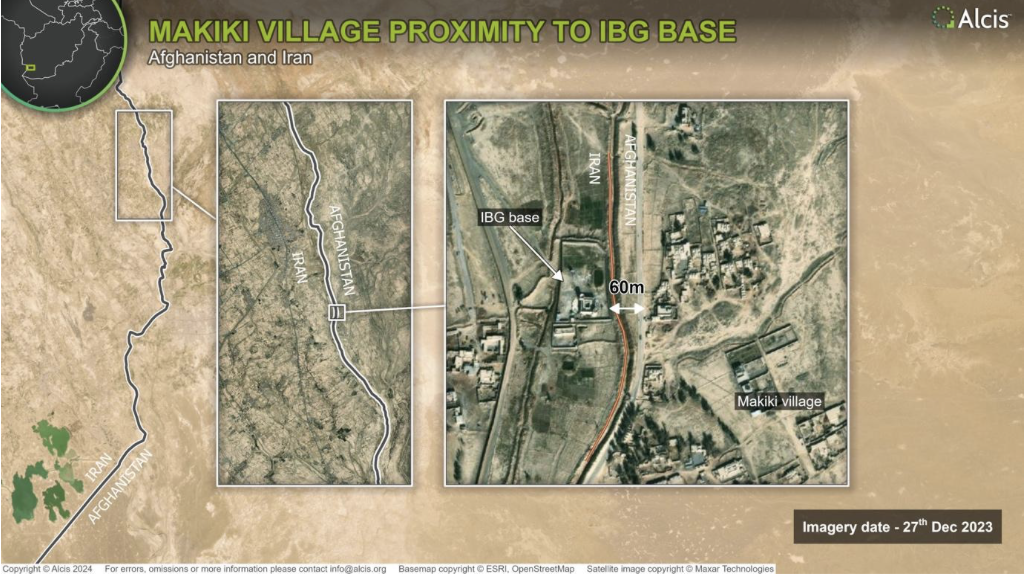

Imagery analysis also revealed that the fighting between Afghan and Iranian forces began in an area where the border populations do not even share common water sources but rather where there is a long tradition of cross-border smuggling (Figure 4). It shows just how close the Iranian border wall is to Afghan farmland and villages, often as little as 60 meters apart. The construction of this border wall increased the potential for the Iranian Border Guards (IBG) to fire across the border and, following the Taliban’s capture of Kabul, increased the likelihood that their battle-hardened soldiers would return fire.

Figure 4. Water flows on the border from Kamal Khan to Kang. Copyright Alcis. Republished with permission (on file with Lawfare).

Further satellite imagery exposed the increased number of catapults used to propel drugs into Iran along this stretch of the border following the Taliban takeover, an indicator of their tolerance of the cross-border trade—a source of increasing frustration among the IBG and, ultimately, the direct cause of the fighting (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Proximity of farmland to Afghan border posts and Iranian border gates near Makiki village. Copyright Alcis. Republished with permission (on file with Lawfare).

Implications of Reduced Surface Water

Perhaps most important, satellite imagery and geospatial analysis were instrumental in identifying how communities in Afghanistan and the Iranian state have responded to a reduction in surface water in the Helmand River Basin through widespread groundwater exploitation and the threat this now poses to the lives and livelihoods of communities across southwest Afghanistan and in Sistan and Baluchestan in Iran.

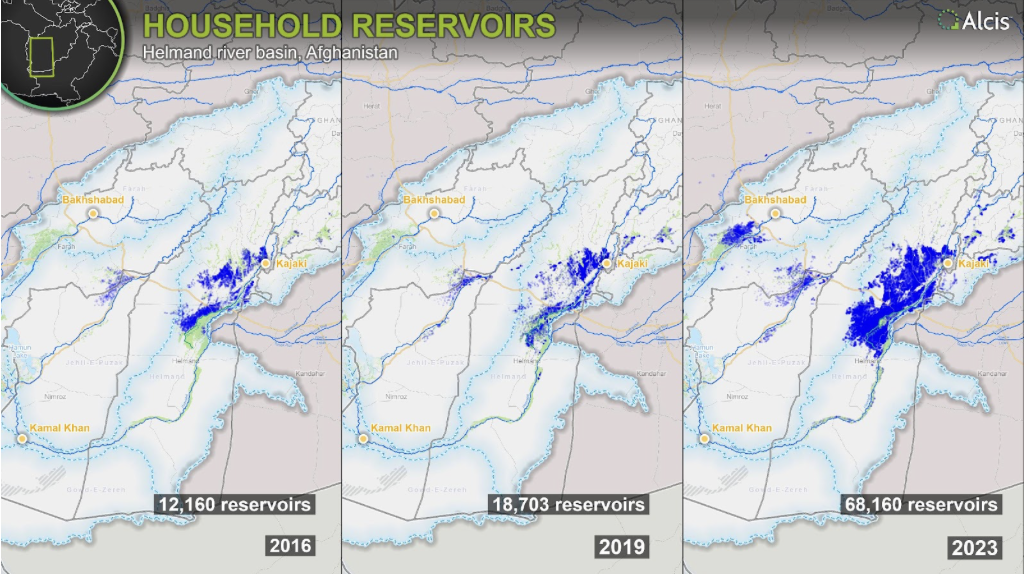

In Afghanistan, access to affordable solar-powered systems has been transformative and has led to ever greater numbers of Afghan farmers installing deep wells and extracting groundwater. Only a meter in diameter, many wells are more than 100 meters in depth and have water drawn from them using a pump powered by multiple arrays of solar panels. While underground, these wells often leave a visual signature—a surface reservoir and solar panels—that can be identified and then mapped using imagery (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Household reservoirs used by those using solar-powered deep wells to extract groundwater (2016, 2019, and 2023). Copyright Alcis. Republished with permission (on file with Lawfare).

Imagery shows that by 2023, there were at least 68,160 deep wells in the Helmand River Basin—five times more than in 2016. While these were at one time used only by farmers looking to settle remote former desert lands in the southwest provinces of Helmand and Farah—often to grow poppies—these deep wells have become ubiquitous, commonly used in surface-irrigated areas where water flows have become increasingly unreliable due to climate change.

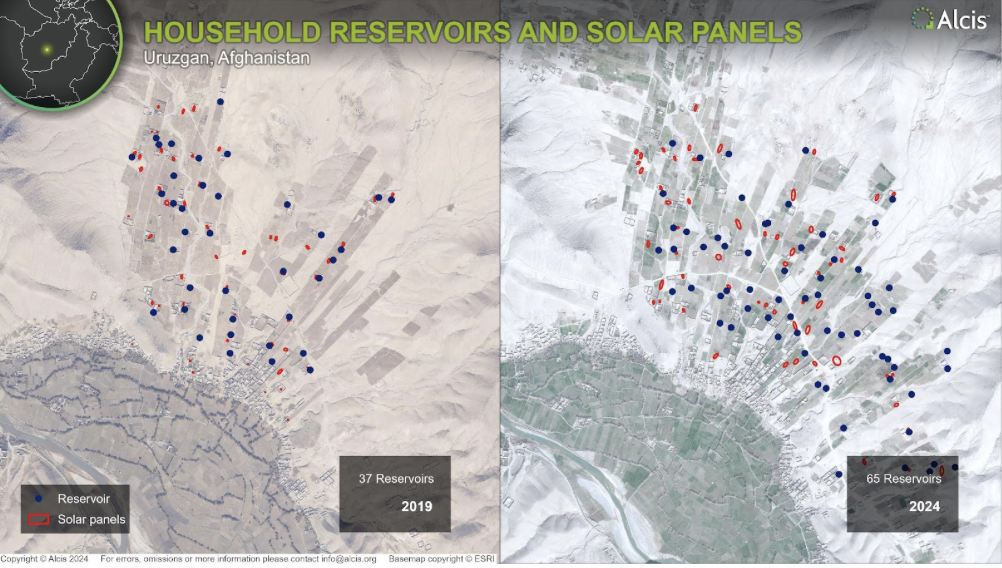

In areas formerly irrigated using traditional irrigation systems—karez—increased temperatures and less precipitation in the Helmand River Basin resulted in reduced water flows and a move to deep wells. As the number of deep wells increased, the karez dried up completely. With many more deep wells installed, groundwater levels are falling at an alarming rate—in some cases, by as much as five meters per year. Some of the earlier, shallower wells dug in the initial years of settling the former desert lands of the southwest have failed, resulting in deeper wells being installed in ever-increasing numbers (Figure 7).

Figure 7. The expansion of groundwater wells in Uruzgan (2019 and 2024). Copyright Alcis. Republished with permission (on file with Lawfare).

In southwest Afghanistan, farmers are increasingly reliant on their deep wells for irrigation and drinking water, leading to increasingly neglected surface irrigation systems (which are collectively managed). This shift toward water as a privately owned asset will likely render the water management problem even more intractable.

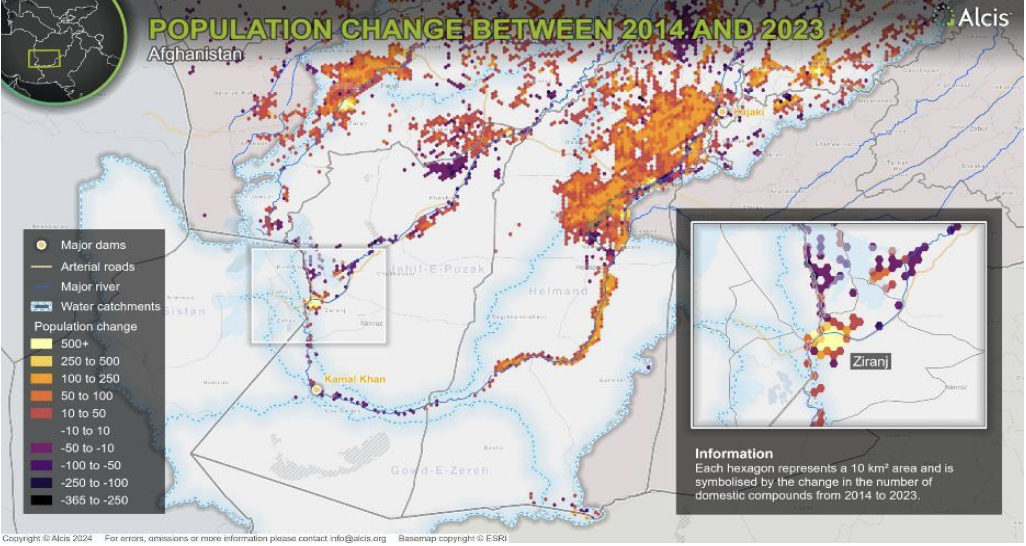

Farmers are aware of the threat this increase in groundwater extraction poses to their ability to continue to draw water, grow crops, and sustain their livelihoods into the future, but they see no other option. In fact, imagery analysis of household compound data shows that over the past decade, population growth in the Helmand River Basin in Afghanistan has coincided with increased groundwater exploitation (Figure 8). Outmigration appears to be restricted to areas that are not only receiving reduced surface water flows due to climate change, but where the groundwater is often salinated and cannot be used for agriculture. This includes districts like Dishu and Charburjak, in the lower part of the Helmand River.

Figure 8. Changing population in Helmand River Basin (2014 to 2023). Copyright Alcis. Republished with permission (on file with Lawfare).

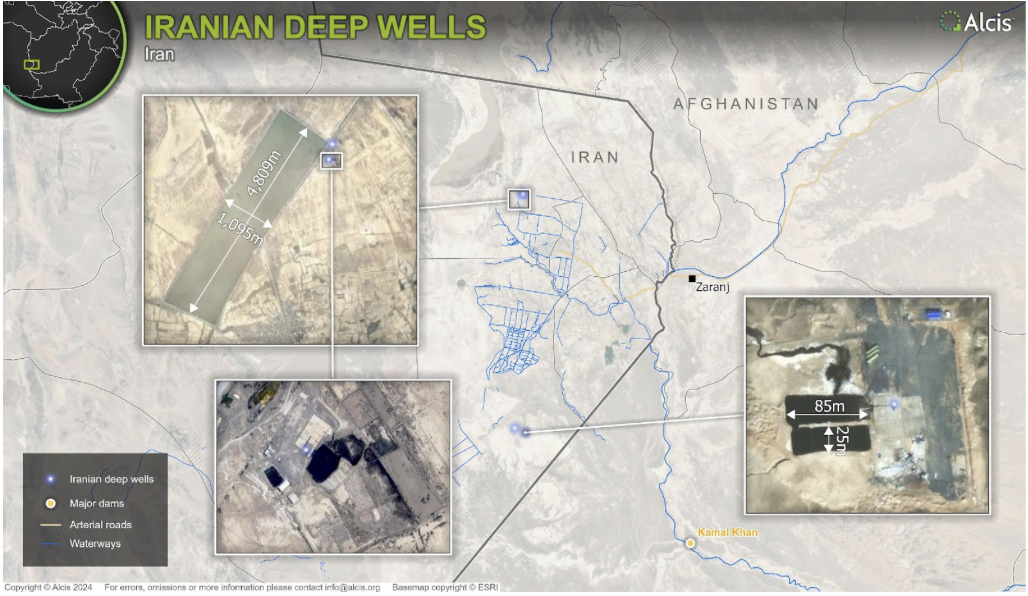

Across the border in Iran, satellite imagery shows the same move to groundwater extraction—however, led by the state and at scale. In Sistan and Baluchestan, we used imagery to identify the location and size of three deep well drilling and water extraction projects (Figure 9). Established in 2019, these wells have been drilled to between 1,000 and 3,000 meters. The reservoir accompanying the well in the district of Nimroz is 27,000 square meters. These three deep wells, as well as the dramatic upswing in groundwater well drilling in the Helmand River Basin in Afghanistan, reflect how state, individual, and community responses to the climate crisis and diminishing surface water sources risk depleting the groundwater that has increasingly become a lifeline for both rural and urban populations in the region; it is literally a race to the bottom.

Figure 9. Location and extent of Iranian deep well drilling operations and water storage (2024). Copyright Alcis. Republished with permission (on file with Lawfare).

The Importance of Using All Faculties

By drawing heavily on geospatial analysis and imagery, our research has gone a long way in recasting and refocusing discussions on transboundary water rights and conflict on the Afghanistan-Iran border. In particular, it has shown the role that Tehran has played in retaining and diverting water from populations downstream, including farming communities in Sistan and Baluchistan—diverging from the narrative that apportions blame solely to Kabul.

Our research has also identified, quantified, and visualized the widespread move to groundwater extraction in the Helmand River Basin in Afghanistan. This trend could, if continued unchecked, threaten the livelihoods of up to 3.65 million people over the next decade. This should spark concern for countries in the region and in Europe, which have often been the final destination for Afghan migrants fleeing war and destitution back home.

By focusing on concrete, observable fact—rather than just discourse—this study has shown that researchers conducting projects in fragile and conflict-affected areas should draw on as many senses as they can to avoid misleading policymakers, while seeking to achieve the best policy outcomes.

This article was originally published on Lawfare.

Since January 2025, an international research consortium led by the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs (NUPI), has been undertaking a research project to improve academic and policymaker knowledge on preventing and managing climate change-related conflict and instability.

The research will improve our understanding of how the Regional Strategy for Stabilisation, Recovery and Resilience (RS-SRR, a joint project of Lake Chad Basin countries, the African Union, and the Lake Chad Basin Commission) and related efforts influence the relationship between climate change and environmental degradation on the one hand, and stability, recovery, and resilience on the other. Based on the knowledge gained from the Lake Chad Basin-specific research, and informed by comparative studies of other similar initiatives, the research will develop a set of generic principles and factors that influence the effectiveness of efforts to prevent and manage climate-related conflict and instability. The intent is that these principles and factors can inform the design and adaptation of climate change-related peace and security initiatives in other contexts.

The two-year project is led by Research Professor Cedric de Coning, and includes Dr. Andrew E. Yaw Tchie, Dr. Minoo Koefoed, and Dr. Thor Olav Iversen of NUPI. The other members of the consortium include Professor Freedom Onuoha from the University of Nigeria-Nsukka, Professor Saibou Issa from the University of Maroua in Cameroon, Dr. Thomas Gonzales and Dr. Dirk Bruin from the Center Leo Apostel (CLEA) ) at the Free University of Brussels, and Louise Lieberknecht and Natalia Skripnikova from GRID-Arendal.

Climate change, conflict, and resilience

All over the world, the effects of climate change are exarcerbating existing vulnerabilities and increasing the risk of inter-communal tensions over land, water, and food. The UN’s New Agenda for Peace (2023) predicts that failure to tackle challenges posed by climate change will have devastating effects for peacebuilding objectives. The knowledge gained from this project is intended to help others facing similar challenges by providing insights into how locally led initiatives can bolster resilience and prevent and manage conflict.

The Lake Chad region and the wider West African Sahel belt are experiencing the compounding effects of violent conflict and climate-related extreme weather events that have caused large-scale population displacement and that have further increased water- and food insecurity. In response, several countries bordering the Lake Chad Basin (Cameroon, Chad, Niger, and Nigeria, and Benin), in collaboration with the Lake Chad Basin Commission and the African Union, developed the RS-SRR. This strategy, together with its enablers and related processes, provides this project with an interesting case study of how one specific region is attempting to manage climate and environmental-related conflict and instability.

It is a multi-stakeholder effort, in which the governors of the territories bordering the Lake Chad Basin, together with traditional leaders and civil society, serve as key drivers and implementers of the strategy. Other stakeholders at the national, regional, continental, and international level provide political, technical and financial support at multiple scales. The strategy is aimed at generating holistic and whole-of-society changes that address both the symptoms and underlying drivers of instability across the Humanitarian, Development, and Peace (HDP) Nexus. The strategy and related efforts represent an attempt to go beyond stabilisation by including recovery and resilience in the overall framing of the problem and its solutions, and this highlights the importance of addressing shared challenges in a way that fosters collaboration among a diverse range of sectors and stakeholders.

The Lake Chad RS-SRR is a response to three separately identifiable, but deeply interrelated, cross-cutting and mutually reinforcing crises: (1) a structural and persistent development deficit, (2) a breakdown of the social contract that had manifested in lawlessness and a violent extremist insurgency, and (3) a climate change-related environmental disaster. In the context of the deep complexity that characterises efforts to holistically manage such a multifaceted crisis, the research project has developed a conceptual framework for analysing interventions that aims to influence climate-related peace and security risks. The framework consist of five interrelated dimensions, namely (1) integration and the Humanitarian Development and Peace (HDP) Nexus, (2) localisation and context specificity, (3) multi-stakeholder participation, (4) adaptation, and (5) knowledge production and learning.

The project will use this conceptual framework to analyse how the Lake Chad stabilisation strategy and related efforts are structured and coordinated, as well as its influence to date. The project aims to identify and analyse key social-ecological factors that influence adaptation choices at local to national levels, with special attention to analysing the role of social cohesion, adaptive capacity, and societal resilience. This will inform how stabilisation, recovery, and resilience efforts can support conflict-sensitive and peace-positive adaptation, and can be used to help guide similar response initiatives elsewhere in the world.

Since April 2023, the conflict between the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) has triggered the world’s largest and fastest-growing displacement crisis: over 12.8 million people have fled to neighbouring countries. Despite the significant scale of the conflict and the resulting death toll, the conflict is regarded as a “forgotten war”, and the humanitarian response has been insufficiently funded.

Focusing on the situation of women Sudanese refugees in Eastern Chad, Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) and its Chadian partner BUCOFORE carried out field research in the refugee camps of Farchana, Breidjing, Djabal, and Irdimi in April and May 2024. The research employed a mixed-methods approach based on a perception survey and qualitative interviews to centre women’s experiences. Three demographic groups were identified: newly arrived Sudanese refugees and Chadian returnees displaced by the ongoing conflict between the RSF and the SAF, long-term Sudanese refugees displaced since the Darfur crisis in 2003-2004, and local communities in Chad.

Humanitarian aid falls short

As more refugees arrive in Chad, humanitarian aid remains insufficient to meet the growing needs. Chad hosts over 844,000 Sudanese refugees and Chadian returnees. That’s on top of the 400,000 Sudanese refugees who have fled since the Darfur conflict in 2003-2004. While the 2004 humanitarian response plan in Chad was funded at 87.9 percent, only 45.4 percent of the 2023 plan received funding. Despite an overall increase in funding on average since 2016, available resources cannot keep up with the rapid escalation of needs, resulting in gaps in assistance and a failure to protect refugees.

In November 2023 and March 2024, the World Food Programme (WFP) warned that unless more funding is received, it would be unable to continue providing life-saving assistance in Chad.

“When we arrived here in Chad (2004), the humanitarian organizations helped us a lot. They really lived up to expectations. Nothing was missing. But in recent years, they have stopped helping us. We manage to provide for ourselves and our children. There are a lot of us here now. The water points are no longer sufficient. There is no more wood around, so we have to go a long way to get some. Medicines are no longer available at the health centre, and we no longer receive assistance. People are selected to receive it. It’s not like before.”

Sudanese refugee in Djabal Refugee Camp, Chad

Our research shows that while 74 percent of respondents received emergency assistance when they arrived in Chad, this proportion is higher among long-term refugees than among those recently arrived.

Women’s perceptions of and satisfaction with humanitarian assistance

On arrival, most women refugees receive food, water, medical assistance, and shelter. However, distributions are impacted by the funding gap. The WFP declared that “activities received only 50 percent of the required funding, which represented a decrease compared to the 61 percent level of funding in 2022”. These observations are supported by the refugees who report limited amounts of basic needs such as food and water. “I was given buckets and a mat, but the help isn’t enough. No one even asks us what we want. We need food and water—the two most important things—but it’s so hard to get them”, reported one refugee in Irdimi Refugee Camp in Chad.

The need for a gender-responsive humanitarian response in the camps

While all refugees share economic needs, women and girls have gender-specific needs, including maternal and reproductive health services, protection from gender-based violence, and economic empowerment. 65 percent of Sudanese refugees and Chadian returnees did not feel that the assistance responded to their specific needs as women. 33 percent of respondents attributed the deficiencies in aid to the assumption that everyone in the camp has the same needs.

This underlines the complex challenges facing humanitarian responses: urgent needs such as food and water have to be balanced with longer-term needs such as education and economic opportunities. One young newly displaced Sudanese refugee in the Farchana refugee camp in Chad perceived access to education to be her primary need as a young woman. The responses show that needs are not only influenced by gender, but also shaped by intersecting factors such as age, socio-economic status and opportunities. Another recently displaced Sudanese refugees in Farchana said: “As a mother, I am debilitated by the situation that my children are going through. To see them starving, without medicine and without education, disgusts me.”

Since the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) adopted its first Policy on Refugee Women (1990), there has been significant progress in recognizing the specific needs of refugee women and girls and the necessity for gender responsive humanitarian action, such as the UN Security Council Resolution 1325 (2000) and the establishment of the Women, Peace, and Security agenda. Gender mainstreaming has become a feature of humanitarian aid in most contexts. Yet, gender responsiveness remains limited in practice, particularly in situations of displacement. In addition, gender policies remain generic and fail to account for contextual specificities. Ensuring that refugee women and girls are protected from all forms of gender-based violence, trafficking, and exploitation, and are given access to education and economic opportunities, remains an enduring challenge.

The international responsibility in supporting populations amid conflicts

In a highly uncertain and increasingly conflict-afflicted world, where millions are forced to flee their homes, supporting populations in need is critical. The ability of humanitarian actors to respond to needs primarily derives from the mobilisation of funds. But shifting donor priorities and concurrent humanitarian crises have turned the armed conflict in Sudan into a neglected crisis. UN agencies and NGOs have denounced these funding discrepancies, which exacerbate the plight of displaced people. The US aid cuts will worsen the situation not only in Sudan and Chad but globally, multiplying crisis hotspots and humanitarian emergencies. It is imperative that the humanitarian response matches the scale of the Sudan crisis. The international community must act decisively to support millions of displaced people and refugees at risk of starvation in Sudan and in neighbouring countries.

The war in Sudan must no longer be treated as a forgotten crisis. Sudan stands at a strategic crossroads, not only for Africa, but also in terms of broader regional and global stability. As the conflict continues to displace and plunge millions into suffering, Sudan demands urgent attention from global powers, humanitarian organizations, and regional actors alike. Diplomatic efforts must be intensified to bring all stakeholders to the negotiation table, especially as the risks of partition grow, involving the two rival factions (SAF and RSF), regional powers, and international actors. Diplomatic efforts, and the involvement of major regional actors as well as the UN, are crucial to finding a peaceful resolution to this protracted conflict.

Could you please introduce yourself and your role in the XCEPT programme?

I’m Dr Costanza Torre, and I’m the lead researcher on the South Sudan branch of the XCEPT programme at King’s College London. Our team at King’s is focused on understanding why, in fragile and conflict-affected states (FCAS), some people seek peace and reconciliation, while others pursue violence. In the case of South Sudan, we’ll be analysing this by carrying out a survey and qualitative interviews to understand what role mental health and exposure to conflict, among other factors, play in informing people’s choices of peaceful or violent behaviours. We are hoping that these findings may inform policy decisions around reconciliation. As the South Sudan lead, I’ve been helping to shape the research design, recruiting local researchers, and guiding the implementation of the research.

Tell us about your background. What were you doing before you joined XCEPT?

I describe myself as a medical anthropologist and critical mental health researcher, which is basically a way to make sense of my very interdisciplinary background. I started off by doing a BA and an MA in clinical psychology, but over the course of my studies I realised that I wanted to consider matters in a much more anthropological way. This led me to join a research project in northern Uganda exploring the reintegration of former child soldiers that had been abducted by the Lord’s Resistance Army – with a focus on the psychological consequences of stigmatisation during the reintegration process. After this, I continued working in northern Uganda for my PhD, which I completed in the London School of Economics. Over fifteen months, I lived in Palabek refugee settlement, which was almost entirely inhabited by South Sudanese refugees, and I carried out an ethnography of the mental health and humanitarian interventions that were being implemented in the settlement.

The entrance of Palabek refugee settlement. Credit: Costanza Torre

Northern Uganda was a really important area to research this, because Uganda currently hosts 1.8 million refugees, which is the largest refugee population in Africa, and the sixth highest refugee population in the world. The field of humanitarian psychiatry is undergoing immense expansion, and during my fieldwork a lot of NGOs were implementing mental health interventions around the settlement where I stayed, so it was really interesting to look at what kinds of programmes were being implemented and the reasoning behind them. This showed how international organisations were understanding the experience of refugees and what issues they thought needed addressing. There’s a huge focus on the role of culture in shaping suffering, and rightly so, but I found that very often the socioeconomic context in which someone is living was ignored.

Often, ‘cultural’ factors are evoked to explain why people don’t really engage with emergency mental health interventions. Humanitarian workers and academics often think that, as these interventions rely on biomedical models, they don’t match the way in which people understand their own suffering, which may involve cosmological and spiritual elements, for example. And while sometimes this may be true, in contexts of chronic poverty and food insecurity, people are also unlikely to engage with mental health interventions because they don’t understand them as helping. They see them as tackling problems only in the mind, whereas what they really need is change in their actual circumstances.

My fieldwork had a strong focus on the social determinants of mental health, and I tried to understand the psychological suffering of refugees away from their clinical dimensions, and rather as being linked to the present context, which is the way in which people usually understand and explain their suffering. For example, someone might say that yes, they experienced trauma due to displacement or exposure to conflict, but the cause of their present suffering is actually a result of food insecurity. Throughout my work, I’ve tried to expand on the notion of ‘psychocentrism’, and challenge the idea that, because manifestations of distress are psychological, then the causes of the distress are psychological, and the solution needs to be psychological as well.

The slogan for the celebration of World Mental Health Day in Palabek refugee settlement, October 2019. Credit: Costanza Torre

Do you think there’s scope to run interventions that combine mental health and socioeconomic support, or should the priority be on addressing people’s living situations?

That’s a very good question. As a clinical psychologist, I definitely see the value in mental health interventions, especially if we’re talking about situations in which symptoms may be particularly acute, or if somebody is suicidal or potentially violent. The problem is that we keep separating these two realms, whereas they’re not divided at all. It doesn’t make sense to think of, for example, food insecurity as one thing and mental health as another, because the experience of not having enough food is already a deep psychological experience of suffering and uncertainty.

This tendency to separate the socioeconomic reality from the psychological one doesn’t stand up against anthropological research which tells us that socioeconomic factors are deeply embedded within people’s ‘lifeworlds’. People’s lives are fundamentally shaped by their network of social relations – and social relations are embedded in, and hugely linked to, socioeconomic factors, such as how much food you may have at your disposal or what your housing situation is.

One other point about mental health interventions that’s important to note is that, often, they’re predicated on a strongly individualised model. They look at symptoms, and they look at the individual. This fits in very well in the world of humanitarian interventions which are often focused on ideas of self-reliance and individual resilience, but what we know – and what anthropologists have been saying over and over again – is that this often does not mirror what people care about and the way in which people actually live. People exist in networks, they exist in relationships, and an emphasis on self-reliance doesn’t make sense to societies that are deeply structured by caring responsibilities.

Refugees walk to the Health Centre III in Palabek refugee settlement. Credit: Costanza Torre

Where does South Sudan fit into this model? Is its society structured or understood in a more relational or individual way?

In South Sudan, personhood tends to be extremely relational. Individuality of course exists, but it’s not valued as much as relationships, and people’s worlds often revolve around extended families. This has huge implications for people’s lives, as it puts enormous pressure on the performance of social roles. For example, what we’ve seen in some of the initial findings from our research in South Sudan is how much the value of cattle is linked to men’s ability to be able to perform as a man and to provide for their family. This expectation exists across society, because it’s very often an understanding that is enforced relationally and specifically by women’s practices. For example, in some regions of South Sudan, it’s common for women to write and sing songs praising men that have been particularly good at behaving like ‘men’, while emasculating and mocking men who haven’t lived up to these expectations.

There’s a concept called ‘lived pragmatism’ that I find very helpful in understanding South Sudanese society. It comes from the social and moral anthropology of Africa, and it’s used to explain how, among certain societies, what is real about people is what can be observed from the outside. When it comes to ideas of masculinity, this means that, until you’re seen by others to perform as a man, you often cannot be defined as one. Because personhood is so relational in South Sudan, the idea of not being valued by society is particularly existentially threatening and can have a huge impact on a person’s wellbeing. This was something I saw first-hand during my fieldwork in Uganda, where the inability to work and to provide had enormous consequences on the mental health of South Sudanese refugees. During the dry season, when food shortages were felt in a particularly acute way, depression rates would skyrocket in the settlements. My research suggests that this was related to the heightened stress of resource scarcity, but also to the fact that being unable to perform relational gender roles, such as providing for one’s family, made it even more difficult for people to see a future for themselves.

A refugee shows the small onion harvest he got due to little rain and climate change in Palabek refugee settlement. Credit: Costanza Torre

And this raises another significant issue with mental health humanitarian interventions. Interventions narrowly based on notions of trauma and post-traumatic stress disorder often put the

emphasis on addressing the past traumatic event, and assume that forms of suffering are generally rooted in past traumas. Yet, for many people, causes of suffering are rooted in present circumstances and in their worries about the future, so there’s this temporal disjuncture between intervention priorities and people’s actual experiences. This is a theme that has come up time and time again in my research. It seems to me to point to the fact that, in academic research, knowledge needs to be generated from below and co-produced with – rather than extracted from – local researchers and research participants, to make sure that humanitarian programmes address the real needs of their recipients.

Why did you choose to work on XCEPT?

XCEPT to me was incredibly exciting because it offered an opportunity to work on South Sudan and to expand the knowledge that I already had from working with South Sudanese refugees. It’s also been amazing to be part of such an interdisciplinary team, and to rely again on some of my expertise and skills as a psychologist.

One thing I’ve found really valuable is being able to work so closely with local researchers in South Sudan, to get an idea of the context they are embedded in and to learn more about how they understand their country’s situation. I feel incredibly grateful that we’ve been able to find the people that we did, and they all bring such diverse expertise, commitment, and nuance to the job. The highlight of my work on XCEPT so far has been to spend time in Juba collaborating with the South Sudanese researchers. When designing the research, we tried to construct questions that were really attuned to the context in South Sudan, but when we discussed them with the researchers, we were confronted with the amount of our own inaccurate assumptions that had shaped the questions in the first place.

For example, the researchers explained that questions around causes of violence in instances in which killing had taken place may only be relevant if they were about the accidental killing of a person perceived as innocent. If the killing was a form of revenge, then the ‘victim’ would be seen to be deserving of that kind of punishment, which has enormous implications for how we conceptualise justice and reconciliation in South Sudan. By working together with the local researchers, we were able to deconstruct our questions and rebuild them in a way that will make more sense to the people that will be answering them.

A sign in Palabek settlement encourages refugees to seek mental health support at the local health centre. Credit: Costanza Torre

What do you hope the XCEPT project will achieve?

There are such incredible people working on our team, both in the UK and in South Sudan, and so I hope that our research will be able to provide a nuanced understanding of lived experiences of conflict. When we talk about mental health using a symptom-based model, it can lend itself to the victimisation of people that have lived through violence. By conducting research in a way that closely

involves people on the ground, I think it reopens the space to talk about the human experience of conflict, which can often be a story of enormous resourcefulness and strength.

Ultimately, I’d like a really strong emphasis to be put on addressing the things that actually matter to people. I’d like XCEPT to be able to give recommendations, to the FCDO or any other international organisation with power to implement change, that priorities should be chosen from the bottom up, and interventions should be based around what matters to people in their lives.

In the coastal province of Cabo Delgado in northern Mozambique, what began in October 2017 as a series of deadly attacks by an armed group has escalated into a full-scale civil war. Known locally as ‘al-Shabaab’ (although distinct from the Somalia-based terror group of the same name), the group has waged a violent insurgency, causing widespread displacement and food insecurity. The region is rich in natural resources, and conflict is deeply intertwined with enormous mineral and hydrocarbon discoveries in the region in the 2010s.

Despite widespread recognition of the dynamics that have driven conflict on the Mozambique-Tanzania border, research has mostly focused just on causes and effects, without addressing the lived realities of communities in the borderlands. Recent research conducted by Bodhi Global Analysis on the border of the two countries reveals how gender and geography shape people’s experiences, creating impacts that have often been overlooked, outlined in this blog.

The prevailing nature of gender norms in conflict

Research found that men’s and women’s involvement in the conflict broadly aligns with existing gender norms and remain either unchanged or even reinforced. Most fighters and leaders of al-Shabaab are men, who also make most of the tactical decisions and carry out most attacks. Women, by contrast, have often been forcibly recruited into al-Shabaab through abduction or forcibly married to al-Shabaab fighters as a means for their families to secure protection and income.

Economic factors largely drive some of these roles. Recruitment into al-Shabaab allows men to fulfil gender-based expectations around providing for their families in a context where economic opportunities are scarce, and poverty levels are high. Where men have lost their livelihoods, they have found dominant ideas of masculinity challenged, pushing some into alcoholism, and, in turn, increasing rates of domestic violence. Despite this, women have expressed that, despite the economic burden they faced themselves, they were sympathetic to a belief that men were suffering from an inability to fulfil traditional roles as providers. The reality of this, of course, has been that men have effectively escaped accountability for physical violence.

Gendered experiences either side of the border

Cross-border trade has traditionally been dominated by men on both sides, who acted as the primary providers for their families through commercial activities like farming, fishing, and casual labour in agriculture and construction. This is enabled by a lack of restrictions on men’s mobility, allowing them to take advantage of cross-border transport methods like motorcycle taxis, boats, and buses. Where border closures have occurred, men in Mozambique have tended to seek informal labour in agriculture. In Tanzania, however, this has pushed many into joining al-Shabaab and migrate out of their community area.

The effect on women, however, is much greater. Women are often confined to more domestic household roles, or engage in some smaller scale income-generating activities to support families. Facing greater restrictions on mobility and access to resources, as well as increased risks of physical violence, many gender norms have changed for the worse in hard times. Insecurity and the loss of men to the conflict has led to an increase in female-headed households; these women bear a double burden of financially supporting their family while supporting their obligations at home. Where many women have relied on the incomes of husbands, they have been driven to desperate measures to provide for their families when these men have left or lost income opportunities. This has been seen in an increase in the prevalence of transactional sex on both sides of the border, as well as through the marriage of women to al-Shabaab fighters in Tanzania.

Between vulnerability and opportunity: women’s agency in the conflict

Despite the challenges women face, female heads of households have increasingly become involved in community leadership, which has traditionally been reserved for men. This conflict has thus created a space for women to assert agency by taking on these responsibilities. This, however, is rare, and prevailing gender norms continue to form a significant barrier to women’s empowerment. Some women cited joining armed groups as a means of gaining agency: women have sometimes joined al-Shabaab voluntarily, working as spies or in other supporting tasks such as transporting money and weapons across the border.

Rethinking gender in conflict zones

The findings from the borderlands research challenge conventional gendered narratives on conflict dynamics: men are not always perpetrators of violence, and women are not simply one-dimensional victims of armed conflict. The conflict has exposed a number of risks and opportunities for women in particular. For policymakers and humanitarian actors, this highlights the need to rethink approaches to gender in conflict, in a way that considers the range of roles that men and women might play. Crucially, it means more accurately addressing the drivers behind women’s support of and participation in armed conflict, supporting the creation of livelihood opportunities, community initiatives, and targeted support that addresses women’s social and economic needs. Only by moving beyond assumptions and recognising the full spectrum of gendered experiences can responses by impactful and sustainable.

Russian forces have carried out sexual and gender-based crimes (SGBC) against Ukrainian civilians and prisoners of war since the beginning of Russia’s aggression in 2014. Since Russia’s full-scale invasion in 2022, such crimes have skyrocketed in their gravity, frequency, territorial scope, and victim spectrum. According to the United Nations Independent International Commission of Inquiry on Ukraine, victims include girls and boys, women and men from ages four to 80. Russian military and occupation authorities perpetrate SGBC “with brutality, and in combination with other grave violations” such as inhuman treatment, torture, unlawful detention, enslavement, unlawful killings and, summary executions, according to the UN inquiry report.

Ukraine’s responses to these crimes have focused on both criminal justice and reparations for the survivors. The Ukrainian government, human rights NGOs, and international stakeholders have contributed to the documentation and prosecution of direct perpetrators and their commanders for SGBC. In 2022, the War Crimes Department of Ukraine’s Office of the Prosecutor General established a focused unit on conflict-related sexual violence (CRSV). As of November, Ukraine had 326 CRSV cases, of which 117 concerned male victims.

Ukraine is also pursuing reparations. The government is striving to provide comprehensive medical and psychological support, vocational training, and other measures to help SGBC survivors and their families heal and feel empowered to move forward. In 2024, Ukraine implemented a pilot program for urgent interim reparations for CRSV survivors. As of December, 607 survivors (354 men, 241 women, 10 girls, and two boys) applied for reparations under the program. Out of them, 379 survivors (202 men, 172 women, four girls, and one boy) received urgent interim reparations. In late 2024, Ukraine’s parliament supported a more long-term reparations policy. Whether it’s pursuing criminal justice or assessing the need for reparations, the Ukrainian government is trying to take advantage of technological tools to help bring justice for Ukrainian survivors of these crimes, but the process is not without challenges.

Two key factors determine whether and how technology is used: first, the type of response (whether it is criminal proceedings or a reparations process); and second, the stage of response (with or without survivors’ engagement). The following issues have emerged as Ukraine has expanded its use of technology for SGBC investigations.

Server security: Server security is foundational to ensuring the integrity of collected data and, crucially, survivors’ private information and therefore personal security. Prosecution and reparation teams have adopted different strategies for where to house servers storing sensitive information. Stakeholders who keep servers with SGBC information within Ukraine stress Ukraine’s expertise with repelling cyberattacks. Those who use servers outside Ukraine do so with the understanding of the cybersecurity reputation of the chosen jurisdiction. In these situations, only a limited number of professionals have access to the server-stored information, through a multi-step authentication process.

Engagement with survivors: Ukraine’s pilot program for urgent interim reparations for SGBC has been commendably flexible in allowing both online and in-person, on-paper applications. Although the online process offers more convenience, some survivors – particularly older people, or survivors from rural, poorer, or less tech-savvy backgrounds – prefer having human, especially peer-to-peer engagement. This includes peer-to-peer communication with survivors further along in the recovery process and/or those who are engaged in SGBC awareness-raising. This in-person engagement can also include the involvement of trusted civil society lawyers, local paralegal professionals, and psychologists. Such direct human contact facilitates accounts, which are consequently more nuanced and less retraumatizing (as much as it is possible for horrendous SGBC circumstances). In sum, human engagement proves to be crucial at all stages of communication with Ukrainian survivors. Technology is an important tool, but it is secondary to talking directly with survivors.

Open-source investigations: Open-source data can provide important evidence of sexual and gender-based crimes. It can also be used to establish the broader context of the coercive environment in which these crimes take place and can help to link individual crimes to the chain of command. Both criminal justice and reparations investigations search for, classify, and analyze non-confidential, open-source public data (such as social media posts) for evidence of conflict-related SGBC. Initially, there were doubts in Ukraine about whether open-source materials could be used for SGBC investigations, since SGBC tends to take place indoors and in private. However, open-source materials are useful for identifying SGBC red flags such as: the separation of males and females during filtration or other procedures by Russian occupying authorities; footage of forced nudity or executions of naked and/or burned or otherwise mutilated victims; satellite or drone imagery of detention centers, especially amid the mounting evidence of Russia’s policy of widespread and systematic torture, including sexual violence; and social media posts, intercepted communications about, and other footage of batons, sticks, recording equipment, “tapik” field military telephones, and other objects often used for physical and mental sexual torture.

Open-source materials can also help to reduce the number of survivor interviews needed and, thus, can help to minimize re-traumatization. However, they are not enough on their own for establishing SGBC in an armed conflict context, for which survivors’ and witnesses’ statements remain the core source.

Technological training: A significant challenge for criminal justice professionals involved in SGBC investigations in Ukraine is the lack of proper training for newly introduced technology. This lack of training has led investigators to make operational mistakes while conducting interviews and/or working with evidence while using technology, resulting in the production of inadmissible records or, in some cases, even loss of testimonies and evidence. Although technology can enhance efficiency in investigative processes, it must be used correctly to ensure a survivor-centered approach. Ukraine’s criminal justice professionals require more training regarding the newest available technology and its secure use. Such training should be regular and equally reach all criminal justice professionals: investigators, prosecutors, judges and their staff. Finally, training should benefit professionals across Ukraine, especially those in the most affected northeast and southeast regions.

Informed consent, procedural clarity, and data security: In prosecution and reparation processes involving technology, Ukrainian SGBC survivors emphasized that they require clear and respectful explanations of how the information they provide will be digitally stored and used, and the security protocols that will be applied. Some survivors are concerned that they have not been provided with this information. As survivors stress, and international standards require, even with the utmost security protocols for the digital preservation and processing of their data, survivors must be kept informed through accessible and respectful explanations. For open-source investigations, engaged actors should at all times consider the degree of a possible exposure of a survivor’s identity and, where needed, try to seek their consent to respective proceedings. Instruments such as the Open-Source Practitioner’s Guide to the Murad Code could offer helpful guidance.

AI and other tech abuse by perpetrators: A third significant challenge for both prongs of SGBC responses is identifying AI- and other artificially generated “evidence,” specifically designed and planted in the public domain to compromise investigations. Russian perpetrators often use more “traditional” technology such as recording sexual and other abuse and sending harrowing pictures and videos to victims’ loved ones, to blackmail them into dropping charges, devastate them or dissuade them and other Ukrainians from armed resistance, to avoid similar abuse. Investigators require regular training on AI-related abuse and its key identifying flaws (for example, persons whose hands have more than five fingers in AI-generated “photos”). The state and first responding human rights NGOs should also provide constant psychological and cybersecurity advice to survivors and their families considering possible atrocity footage coming from perpetrators.

Technological progress is expanding investigative toolkits in real time. The challenges outlined above, however, underscore the necessity for continuous ethical consideration, adaptation, and cross-sector collaboration in the use of technology, to ensure justice which is both empathetic and effective for SGBC victims and witnesses.

For example, SGBC survivors in Ukraine are not always ready to communicate with more than one investigator in the room. Therefore, the classic two-person documentation approach (with one person asking questions and another recording the exchange) often cannot be used. In many cases, survivors do not give consent to the use of any type of recording device, except for written notes. Such circumstances put significant technical responsibilities on the interviewer, as they need to maintain eye contact and type or write the information they receive simultaneously. The challenges in doing so lead to the deterioration of humane interactions and personal connection that are very much needed during trauma-informed interviews. In such cases, investigators feel that they would benefit from the development of accessible software that accurately transcribes oral questions and answers, or that can turn written notes into typewritten transcripts. Such technology would allow the interviewer to keep their attention on the interviewee and would improve the efficiency and accuracy of the recorded testimonies while mitigating the secondary trauma on the interviewer, sparing them from going through the traumatic narrative again when deciphering the notes.

Another important area of improvement concerns data preservation. International experience demonstrates how the suspension of mandates, the lack of transfer protocols, and the non-availability of secured storage platforms can undermine the most meticulously assembled evidence. The recent shutdown by the Trump administration of Yale University’s database tracking Ukraine’s deported children is a striking example of why pre-emptive data preservation strategies are crucial. In the context of Ukraine, all involved stakeholders—prosecution, reparations actors, and human rights NGOs working on the documentation and analysis of SGBC—should constantly reassess the security of servers storing or processing SGBC information. This includes considerations about placing servers in Ukraine or internationally. Ukrainian stakeholders should also constantly reassess the reliability of private technology companies providing their support for Ukraine’s SGBC responses in light of the changing geopolitical and U.S. climate. Where possible, technology service providers should be diversified, to represent different jurisdictions and sources of funding, and, thus, mitigate the risks of a sweeping withdrawal.

This article originally appeared in Just Security.

Global conflicts have doubled over the past five years. In 2024, one in eight people was exposed to political conflict.[i] Unsurprisingly, one consequence of conflict is a significant burden of trauma and mental health issues, with more than one in five people in conflict-affected countries reported to be suffering from diagnosable mental health disorders at any point in time.[ii] An even larger number of people are likely to be affected by a wider range of psychosocial problems related to conflict trauma.

Despite this, only 0.3% of health-allocated foreign aid is spent on mental health.[iii] This has wide-reaching implications, ranging from the continued suffering of affected populations to the perpetuation of existing conflict. As part of the Cross-Border Conflict Evidence, Policy and Trends (XCEPT) programme, our multidisciplinary team of researchers at King’s College London is studying the connection between trauma, mental health, and violence in our Impact of Trauma Survey (IoTS), with the hope of informing efforts to break cycles of violence.

Breaking cycles of conflict

It is known that some of those who experience the trauma of conflict are more likely to engage in violence themselves, creating what has been called a ‘cycle of violence’.[iv] However, the role of trauma and mental health problems in driving further violence, or in blocking reconciliation efforts, is under-researched. Using an extensive psychometric survey fielded in Iraq, Lebanon, and South Sudan, we hope to better understand the factors that contribute to people’s attitudes to reconciliation and violence in order to interrupt these cycles.

Alongside the IoTS, we will be testing various psychological interventions through a complementary study in Iraq. Participants will take part in an intervention ‘tournament’, which will test different approaches to promoting reconciliation. The most effective intervention from the tournament will be scaled up in a randomised controlled trial (RCT). By including IoTS participants in these interventions, we can use baseline data from the IoTS to examine in greater detail how psychological interventions work among different subpopulations, and how factors such as mental health might influence how effective these interventions are.

The connection between trauma, mental health, and conflict

Building on existing research, the IoTS examines the psychological effects of conflict exposure on individuals, exploring how trauma and mental health might influence political beliefs and behaviours. Recognising that many participants may have witnessed events such as bombings, experienced the loss of loved ones, or seen people killed, we are looking at the association between these experiences, mental health, and propensity to violence. To capture a more comprehensive picture beyond conflict, we are also examining other trauma that people may have suffered, such as childhood abuse, neglect, and exposure to domestic violence.

We will supplement the quantitative data collected in the IoTS with hundreds of semi-structured interviews and life histories that will allow participants to tell their personal stories of conflict in their own words. This will also enable them to share stories that have been passed down through generations that can contribute to intergenerational trauma. By taking this wider perspective, and using both quantitative and qualitative data, we aim to account for the layered nature of trauma in conflict-affected populations, rather than attributing it solely to war-related experiences, and to avoid reducing it to a narrow clinical conceptualisation of trauma.

How psychology and society interact to drive conflict

While there is an association between trauma-related mental health problems and the risk of using violence, most of those with mental health problems never become violent. This is because a vast range of individual and societal factors interact to shape people’s responses to trauma. People develop in nested contexts: growing up in a family, which is embedded in a community, which is part of a society. Factors at these different levels interact with each other to shape how people think, feel, and behave. Examining individual factors within their broader context can uncover systemic issues, such as government neglect in regions with high rates of trauma and mental health issues.

The IoTS is novel in the way it incorporates wider societal dimensions into its analysis, instead of focusing narrowly on mental health. Participants are asked about a range of social and political factors, including social support, social cohesion, their trust in institutions, identity, experiences of discrimination, sense of threat to their community, and perceptions of their community’s ability to bring about change (known as collective efficacy). Our more open-ended semi-structured interviews and life histories will also ask about wider social experiences, such as social exclusion, social norms, reconciliation, justice, and forgiveness.

Overall, it is the interplay between individual and societal factors that drives violence. Our broad approach will enable us to investigate this interaction, providing a richer understanding of the dynamics at play in conflict and post-conflict settings.

Studying conflict trauma where it is needed most

Many studies on conflict trauma focus on particular population samples, such as army veterans or members of armed groups. To gain a comprehensive understanding of the factors associated with the support of violence or of peace, however, we have recruited participants from varied backgrounds.

Most previous research has also been conducted in WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industrialised, Rich, and Democratic) countries, and so existing measures have typically been developed in those contexts. To ensure relevance, we have worked with our partners in each country, as well as local and regional experts, to ensure that the IoTS is tailored to each context, using locally developed measures where available, or adapting scales for use across different fragile and conflict-affected settings.

In South Sudan, we used the South Sudan Mental Health Assessment Scale, recently developed by a team working in the country, which measures mental health problems in terms commonly used to express and make sense of distress in that context.[v] For example, in South Sudan, people may describe having ‘pain in the heart’ rather than using terms that are more familiar in the West, such as depression. Where locally developed scales were not available, we took a multi-step approach to adapting and piloting existing measures. This included working with local translators to translate measures; carrying out cognitive interviewing with a diverse range of people to establish how they understood the questions and to identify sensitive topics; and pilot testing the measures in local populations.

We hope the development of this survey can inform future research by sharing measurement tools and practical and ethical frameworks for research in conflict-affected settings and, ultimately, making data available for other researchers to use.

How do violent attitudes change over time?

With data collected from 2023 to 2025, the longitudinal design of the IoTS adds another dimension to this research. In Iraq, we are conducting the IoTS in two waves, following up with participants around six months later. This will allow us to examine how changes in individual or social factors – such as mental health or trust in institutions – may alter people’s attitudes toward violence. These findings will be enriched by integrating external data sources, such as the ACLED (Armed Conflict Location & Event Data) database. Using detailed records of incidents of political violence, especially those that occur between survey waves and close to where research participants live, we will explore how these events influence attitudes to violence and peace.

The IoTS offers a unique opportunity to test diverse hypotheses of pathways to violence across multiple countries, leveraging a combination of psychological, social and political factors. By looking at a wide variety of questions, such as how perceptions of injustice predict support for different types of political action, and whether trauma-related mental health problems, collective trauma or competitive victimhood affect attitudes towards reconciliation and violence, we hope this study can inform interventions to break cycles of violence in conflict-affected regions.

As of May 2025, IoTS data collection has been completed in South Sudan (fieldwork was carried out in 2024) and for the first wave in Iraq (fieldwork was carried out in 2024-25). The second wave in Iraq and data collection in Lebanon are set to be completed by autumn 2025. Initial findings will be shared later this year – follow @ICSR_Centre and @XCEPT_Research on X to stay up to date with our research.

[i] ACLED. (2025) Acled conflict index: Global conflicts double over the past five years. Available at: https://acleddata.com/conflict-index/ (Accessed: 18 March 2025).

[ii] Charlson, F. et al. (2019) ‘New WHO prevalence estimates of mental disorders in conflict settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis’, The Lancet, 394(10194), pp. 240–248. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(19)30934-1.

[iii] United for Global Mental Health. (2023) Financing of mental health: the current situation and ways forward. rep. Available at: https://unitedgmh.org/app/uploads/2023/10/Financing-of-mental-health-V2.pdf

[iv] Lumsden, M. (1997) ‘Breaking the cycle of violence’, Journal of Peace Research, 34(4), pp. 377–383. doi:10.1177/0022343397034004001.

[v] Ng, L.C. et al. (2021) ‘Development of the South Sudan Mental Health Assessment Scale’, Transcultural Psychiatry, 59(3), pp. 274–291. doi:10.1177/13634615211059711.

In the last two weeks of February, humanitarian agencies reported 895 cases of conflict-related rape as M23 rebels advanced through the eastern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). According to a United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees official, this was an average of more than 60 rapes a day.

UNICEF officials reported similarly grim figures. Between Jan. 27 and Feb. 2, 2025, the number of rape cases treated across 42 health facilities in DRC jumped five-fold, with 30 per cent of these cases being children.

While immediate responses are needed to stop the violence, provide health care to the survivors and assist the displaced, the pursuit of justice also plays a critical role.

Investigative bodies, including the International Criminal Court (ICC), are increasingly using technology to investigate conflict-related sexual violence. In a recent research project, my team interviewed experts who specialize in conflict-related sexual violence investigations around the world.

The ICC’s chief prosecutor, Karim Khan, visited DRC at the end of February and met with sexual violence survivors. The ICC has the mandate to investigate rape, sexual slavery and other gender-based violence amounting to genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes. The office had reactivated investigations in October 2024.

Investigators start by speaking to survivors, following guidelines such as the 2023 Policy on Gender-Based Crimes or the Global Code of Conduct for Gathering and Using Information About Systematic and Conflict-Related Sexual Violence. The Global Code of Conduct is known as the Murad Code after Nobel Peace Prize recipient and advocate Nadia Murad.

In our research, we found that survivors of conflict-related sexual violence are connecting with investigators through various technologies, such as directly using encrypted apps like Signal. Survivors also go through civil society organizations equipped to take video or electronic statements — Yazda, for example, which works with Yazidi survivors of ISIS crimes in northern Iraq — or via portals like the ICC’s OTPLink. The UN’s Commissions of Inquiry also encourage and receive email submissions.

International courts and investigative bodies are also analyzing open-source information on conflict-related sexual violence, such as videos, photos and statements posted on online platforms. Guided by the Berkeley Protocol on Digital Open Source Investigations, this information can be useful to support witness statements, place alleged perpetrators at the scene of the violations and link incidents into a pattern of similar violence.

For example, the UN Independent International Commission of Inquiry on Syria described how ISIS used the encrypted app Telegram and other online platforms to buy and sell captured Yazidi women and girls across the Iraq-Syria border to sustain its sabaya (sexual slavery) system.

In Ukraine, our study found that the main technology-related concern in open-source data gathering is identifying AI-created and other artificially generated images, specifically designed and planted in the public domain as a form of disinformation or to compromise investigations.

Conflict-related sexual violence is often perpetrated indoors which makes certain technologies like satellite or drone imagery less useful. However, other forms of technology have proven to be beneficial in Ukraine’s investigations. In particular, face and voice recognition software have supported efforts to identify alleged perpetrators.

While Ukraine’s experience points to some successes, investigations into sexual violence committed by ISIS in northern Iraq have been hampered. This is partly due to the lack of automated translation software in the Yazidi language to facilitate the transcription and translation of testimonies.

This speaks to the importance of developing software to translate minority languages spoken in armed conflict zones.

Survivors have expressed concerns about the turn to the digital. They fear that their identities and experiences may be revealed through hacking or poor data handling, which could put them at risk of reprisals from perpetrators or their accomplices. It could also lead to stigmatization and ostracization in some communities, undoing survivors’ efforts to rebuild their lives.

To address these concerns, international courts and investigative bodies have adopted data protection protocols. However, the lack of a standardized framework for the use of technology in the investigation of conflict-related sexual violence remains a significant concern for the investigators we interviewed.

Such a framework would incorporate best practices in supporting survivors providing evidence, tracking and preserving open source information and developing new technological applications.

If there is to be justice for survivors of conflict-related rape in DRC and elsewhere, technology — provided it is used with great sensitivity — will likely be an important and timely aid.

This article originally appeared in The Conversation.

In December 2024, the Assad regime in Syria was overthrown. Today, Ahmed al-Sharaa is acting as the interim president of Syria, at the head of a new transitional government.

What will the future look like for Syria under its new leader? Will the coalition of rebel factions be able to work together to build a stable future for Syrians?

In this episode, Dr Nafees Hamid, Dr Rahaf Aldoughli, Nils Mallock, and Broderick McDonald discuss their research surveying and interviewing Syrian rebel fighters both before and after the fall of Assad, sharing insights into the motivations and values of Syria’s new rulers.

*This episode was recorded before the announcement of the new government. Follow ICSR_Centre on X to stay up to date with this research.

On this podcast, Jon Alterman speaks with Dr. Craig Larkin on Babel, where they explore different approaches to reconstruction and reconciliation following violence in the Middle East. Dr. Larkin is the director of the Center for the Study of Divided Societies at King’s College London and leads research on memory and conflict for XCEPT. His work examines how communal memory shapes and sustains violence.

In early 2025, the March 23 Movement (M23) armed group seized control of Goma and then Bukavu, two major cities in the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). M23’s continuing advance in eastern DRC, in defiance of ceasefire agreements, has terrorised communities and led to mass displacement. The M23 group is a major non-state armed group, but had been relatively inactive in recent years prior to a rapid escalation of violence in 2022, which hit new crisis levels in early 2025 with the capture of the two cities. Over two million people have since been internally displaced in eastern DRC; close to one million people were displaced in 2024 alone.

As Angola and other regional actors attempt to mediate peace talks, civilians are caught in a devastating humanitarian crisis, one of the most critical parts of which is sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV). This not only contributes to displacement, but displaced women are also more at risk of SGBV. Furthermore, signs point to gendered violence worsening: in just the last two weeks of February 2025, UNHCR reported 895 reports of rape made to humanitarian actors.

In order to understand these risks, in December 2024, researchers with the Congolese organisation Solidarité Féminine Pour La Paix et le Développement Intégral (SOFEPADI) interviewed 89 displaced women and 30 civil society organisations working in internally displaced person (IDP) camps around Goma. The overwhelming majority of respondents had experienced or witnessed SGBV; while interviewers were careful to avoid direct questions so as not to induce trauma, dozens of women nonetheless disclosed personal experiences. These interviews show just how vulnerable the population is, and how an already dire situation for women and girls has been made exponentially worse over the past six months. This blog outlines some of the key findings of the forthcoming research report.

The risks and drivers of displacement

Displaced women were extremely likely to have experienced conflict-related SGBV: 97% of those interviewed were victims of or had witnessed violence during the conflict, with some stating that sexual violence had contributed to their displacement. One IDP camp resident stated:

“I was living in Kitshanga and then the war started, but I didn’t leave right away. One day I went to the field and I was raped. That’s the day I left Kitshanga and I came here [to the camp]”.

Members of community organisations working in the IDP camps identified an increase in the perpetration of sexual violence over the course of the conflict, with more women arriving to the IDP camps having suffered sexual violence than earlier in the war. Many women also explained they had witnessed killing and massacres in their home communities. Some women had lost close family members or had themselves been wounded in the fighting.

The vast majority of respondents—over 70% —identified M23 as the direct cause of their displacement. A further 5% indicated that their displacement had been caused by Rwanda’s armed forces, either alone or in conjunction with M23. One woman from Kitshanga, a town over 150km away from Goma, stated that she had been displaced to the IDP camp following “massacres, rapes, and the war…caused by the M23”.

Perpetrators everywhere, protection nowhere

M23 troops were not the only group identified as being responsible for perpetrating SGBV during displacement and in the camps. The crisis has led to widespread gender violence perpetrated by armed groups and forces, including the Congolese military and military-allied militias, civilians, and groups of bandits.

Despite the significant number of international forces operating in eastern DRC, which includes the UN peacekeeping mission, MONUSCO, The South African Development Community mission, and, previously, the East African Regional Force, both civil society representatives and displaced women expressed little confidence in these forces’ ability to prevent SGBV. Goma remains the operational centre of the MONUSCO mission. Yet of the 89 displaced women interviewed, only one identified MONUSCO troops as a group as providing security in the areas surrounding the camps. This is despite MONUSCO being a named option in the interviews. In the eyes of most of the respondents, international forces are simply absent.

Scattered survivors and thwarted justice

Since the M23 takeover, international attention has been drawn to the crisis, and there is renewed focus on by the International Criminal Court on combatting impunity and securing accountability for atrocity crimes. Organisations on the ground, however, remain under-resourced and over-stretched. Access to healthcare (including mental health support), economic support, children’s education, and justice are all severely constrained – a point consistently emphasised by affected women interviewed. Repeated displacement of vulnerable people, including SGBV survivors, is likely to further frustrate attempts at holding responsible actors to account.

With the recent order from M23 for civilians to leave IDP camps, already uprooted women are displaced once again, with little access to humanitarian aid. Civilians have been dispersed, with many unable to return to their villages due to fighting. This repeated displacement and dispersal of vulnerable women has made it near-impossible to track where women are going, to provide necessary and ongoing support, and to record reports of future SGBV cases.

The need for action