Doing research in conflict-affected areas carries particular challenges and risks. In this video edition of the podcast, researchers working in borderland regions of Asia, the Middle East and Africa share their experiences and approaches to conducting fieldwork. Key challenges include engaging with diverse actors, maintaining local networks, and establishing trust with respondents. Our experts also share their thoughts on researchers’ positionality in the bigger picture of conflict response and reduction, and how the pandemic has enabled us to think about data collection in new ways.

This episode features:

Joseph Diing Majok, an anthropologist and researcher at the Rift Valley Institute in South Sudan. His work is focused on the borderland regions between Northern Bahr el-Ghazal state in South Sudan, and Darfur and Kordofan in Sudan.

M Seng Mai and Hkawng Yang Madang from Kachinland Research Centre in Northeastern Myanmar at the border with China. Their recent fieldwork examines the nexus between post-coup conflicts and illicit activities in Kachin State, focusing on the impacts on borderland communities.

Kheder Khaddour, a non-resident scholar at the Malcolm H. Kerr Carnegie Middle East Center in Beirut. His research centres on civil-military relations and local identities in the Levant, with a focus on Syria.

Tabea Campbell Pauli is a senior programme officer with The Asia Foundation’s XCEPT programme, and can be reached at [email protected]. The views and opinions expressed here are those of the authors, not those of The Asia Foundation.

South Sudan is highly susceptible to both protracted conflicts and the impacts of climate change. Before 2011, the country experienced a long and deadly civil war. Disputes continued after independence, with violence often spilling over across borders and into nearby countries. Local impacts of climate change (e.g., droughts, flooding) disrupt economic growth and community livelihoods, potentially contributing to conflict and destabilising the region. Climate adaptation and food security can therefore have important implications for reducing violence, particularly social conflicts that involve local ethnic militias, civil defence forces, and vigilantes.

To test these implications, I collected monthly information on climate adaptation and food security projects implemented by nongovernmental organisations in South Sudan and its bordering countries between January 2012 and December 2022. Such measures include, among others, planting more resilient crops, building dams and granaries, managing environmental resources such as grazing land or water reservoirs, and training locals in more effective sustainable food production.

Unfortunately, I did not find that these types of adaptation projects have any impact on social conflict or civil war. In fact, at least in South Sudan, there was the risk that they might be associated with more conflict. A project manager I interviewed provided one explanation: “South Sudan is a complex crisis country …[while] flooding and drought have led to displacements, people move into new geographies, and conflict scenarios shift.” In these complex situations, adaptation can exacerbate these dynamics, especially if the root cause is political or socioeconomic; or, as another local policy ethnographer explained, “you cannot just ask for a local solution and detach national politics from the local issues.”

However, I did find one interesting exception. Adaptation interventions that emphasised general preparedness – including, for example, efforts to plant more resilient crops, train locals in more effective sustainable food production, and create sharing tools for renewable resources like water – were associated with lower rates of social conflict, both within South Sudan and across the border.

Why might adaptation that emphasises general preparedness help in alleviating violence? One explanation builds on the nature of social conflict actors. Social conflict actors are more prevalent than military, police, or rebel groups in the region because they thrive in contexts of weakened or decentralised government. Because these actors are more dependent on locally-sourced crops and cattle, they may also be more sensitive to the effect of weather shocks upon these resources. Adaptation strategies that emphasise general preparedness can address – albeit imperfectly – a wider range of unexpected weather shocks, reducing the need for violent competition over scarce resources.

Another explanation emphasises the disruptions the civil war caused to local livelihoods. As one policy researcher explained, by emphasising specialised adaptation, “programming tends to incentivize specific livelihood strategies…which do not respond to local livelihood trajectories.” This can increase uncertainty about the future, considering climate change’s effects are hard to predict. In contrast, adaptation strategies that emphasise building general resilience can provide local communities with more flexibility, allowing them to choose whether to maintain traditional livelihoods or, if needed, adapt to new ones.

Regardless of which explanation is correct, the finding that adaptation programs that emphasise general preparedness may help reduce conflict illustrates how important it is to consider a broad set of direct and indirect outcomes when trying to tailor climate adaptations to conflict contexts.

Nevertheless, it can be hard to convince donors who fund adaptation that this approach makes sense. Donors have their own expectations when choosing which project to fund, which leads to “top-down” pressures that often do not conform well to the local realities, where social conflict poses a constant hardship. The problem is that, “[m]ost donors don’t understand the complexities…it’s really difficult to be able on the one hand to put a proposal that supports donor demand but on the other hand, is really context driven,” as one policy practitioner explained.

At the same time, it is imperative to convince donors that considering a wider range of outcomes will improve the chances of success. Understanding how interventions designed to support climate adaptation and promote food security can be tailored to local conditions in conflict settings is crucial. By investing in projects that have a better chance not only of improving adaptation in the immediate terms, but also of reducing the risk of violence, we can improve long term resilience, thereby preventing conflict from disrupting livelihoods and harming adaptation efforts.

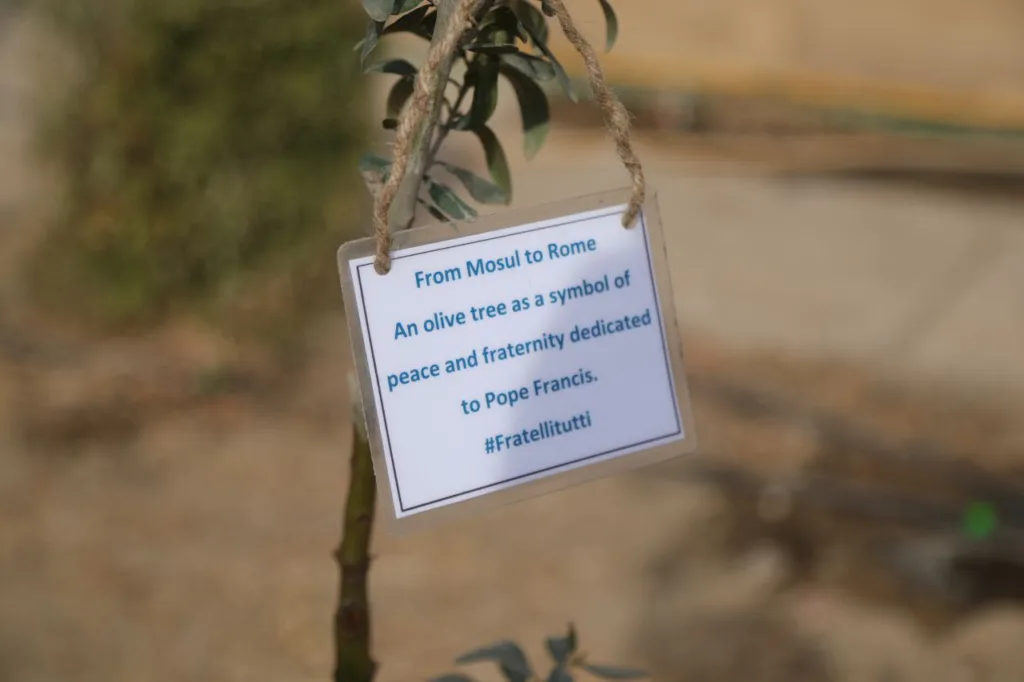

Dr Omar Mohammed is a renowned historian and the voice behind ‘Mosul Eye’, a blog which anonymously documented life under Islamic State (IS) in the city of Mosul, Iraq. Today, the Mosul Eye Association focuses on promoting the recovery of Mosul and its cultural heritage, as well as empowering the city’s youth. The most important task Mosul Eye is undertaking is to promote Mosul globally to replace the negative image of the city after its fall to IS in 2014 and the subsequent destruction.

Hi Omar. Thanks for joining us. Please could you explain what Green Mosul is?

Green Mosul was an initiative started by Mosul Eye, and ultimately led by youth, to plant trees in the city of Mosul, but really it has two definitions. It refers to the greening initiative, which was the effort to repopulate Mosul with green space after the massive estruction that took place during the conflict. But it really aimed at, and can be defined as, an initiative to support reconciliation in post-war Mosul.

Following the conflict, there was a need to bring the people together, and to do that we needed to find something everyone could relate to. We wanted to disconnect them for a short time from the religious and social problems in the city, and we settled on one thing they could agree on: a tree. A tree doesn’t have a religion. It doesn’t have an ethnicity. It only has what benefits the community: clear, clean oxygen, a good view, and the ability to create a nice landscape.

Green Mosul ran from March 2022 to March 2023, and, in that time, we planted 9,000 trees in Mosul and the wider Nineveh province. When we started the initiative, we signed agreements with the local government and with the universities, and one of the terms was that they would commit to planting trees every year. Green Mosul has now technically ended, but the University of Mosul and the Technical University of Mosul continue to plant trees on an annual basis, and the local government has also dedicated a portion of the budget to planting trees every year. Our initiative didn’t stop when we finished our work. We wanted to make sure that it continued and that others could build on it.

Was it easy to get the support you needed to launch Green Mosul? How was the idea first received?

At the very beginning, we sought the support of the Iraqi government, but they wanted to see results before they got involved. I then approached the French government, as I knew they were interested in such initiatives. Their cultural attaché liked the idea, so I went away and developed the initiative amongst the community. One month later, the French government approved the idea, and Green Mosul was borne. Once we’d secured the funds, the local authorities were keen to support us, and we signed agreements with the forestry department, the municipality, the universities, and with other entities in the city. It became a fully Mosuli initiative, where the people and the government were working together for a common interest: the urban greening and, at the same time, the rehabilitation of the social fabric of the city.

Was it important for you to have the local authorities involved?

It was. One of the hurdles to post-conflict recovery in Iraq is that many people see the authorities as dysfunctional. I might agree with them, but I see that there is a way of utilising this dysfunctional government by making it functional – and the only way to make it functional is when you involve them. So Mosul Eye brought the Green Mosul initiative to the government, and they helped make it happen. We didn’t have cars to transport the trees, so we used the municipality’s cars. We didn’t have the ability to create the irrigation system for the trees we were planting, so we used the forestry department. I think their involvement also helped the initiative grow. Members of the public are not necessarily aware of what ‘social cohesion’ is, but they saw Green Mosul as a reliable initiative because of how many people were involved.

Through Green Mosul, we were also aiming to create trust between the authorities and the population. We wanted it to be a collective effort, because the initiative also focused on a very important principle, which is that the process of healing has to be collective in order for it to be strong and impactful. Mosul Eye helped the government to understand the critical importance of social cohesion and of rehabilitating the social fabric, but at the same time, the government gave us the equipment and the space. I think we contributed collectively, and that’s why I always say that this is an initiative of Mosul – it’s not just an initiative of Mosul Eye. It’s important to show the people that they have agency in the process of their healing. They need to own it.

What was the response like among the local community? Were people keen to get involved?

We had a specific communication strategy when we first approached the local communities. We made sure to keep the same distance with the community leaders and the public, because we didn’t want to create the impression that Green Mosul was only for elites. So we spoke to the Yazidis, to the Christians, to the Shia, to the Sunni, and to the endowment administrations of the Yazidis, the Christians, the Shia, and the Sunni. We made sure that the first communication was with the public, and then we facilitated their own communication with their community leaders. Once the locals initiated the conversation, the community leaders came to us, and asked to get involved.

In fact, one of the places where we planted trees was as a result of communication with a woman from Tel Keppe. She told us there was an empty park in the city, and the community wanted to use it to create a space for their children, but the land was owned by the church. It wasn’t easy to convince the church at that time, and distrust between the different religious communities was still strong. We were trying to avoid being labelled religiously – we were trying to be seen only as individuals who had an interest in rehabilitating these spaces – so I spoke to the head of the church and explained that it was a great space. The church would probably receive more visitors if people came to the public park, and everyone would be happy. The priest agreed, and we created a public space where there was both a religious site and a secular site. Today, the same priest is asking me for more trees to be planted.

Within the communities, we also started receiving offers from people saying they didn’t just want trees to be planted in their space, but they wanted to contribute trees to be planted elsewhere. One person also suggested that we plant trees for those lost during the conflict, and then everyone started coming forward with names. They wanted to put the name of their son or daughter, or their mother or father, with this tree or this tree. In the first few months, it was Mosul Eye and the municipality running Green Mosul, and then it became led by the people themselves.

Were the sites where the trees were planted important, or was it more about the process of bringing different communities together?

The two things were intertwined. Some of the sites we chose were religious, because we wanted to try and encourage young Muslims to go to Sinjar and plant trees around the worshipping place of the Yazidis, for example, and young Yazidis to go to Bashiqa or to Mosul and plant trees inside al-Nouri mosque and Al-Saa’a church. We tried to treat these sites holistically, so we communicated to the people of those faiths that we had an interest in their religious space, but, at the same time, they were also heritage sites and public spaces for the people. We did the same in the Shia, the Sunni, the Christian, and the Yazidi majority areas, but there was one condition: that a Yazidi plants in a Muslim side and a Muslim plants in a Yazidi side and so on.

Green Mosul also planted trees in heritage sites, and we had an agreement with UNESCO, whose supervision those sites were under. We planted trees in their sites, but on the condition they would become part of the public space. We always tried to make sure that the planting of trees was seen as being outside the lens of religion – it was a holistic approach that involved everyone.

You mentioned distrust between religious communities earlier – was it difficult to persuade a person from one religion to plant trees at the religious site of another?

At the beginning, it was difficult, and sometimes we needed to have difficult conversations. But we also trained around 25 people from all communities to use as the face of the initiative. They would reach out to their communities, and they would explain that they were there wishing no harm, but they were there to contribute to the community. And when people saw the results – when they went to a place with no trees and when they went back and saw the trees planted – they understood. After a short time, things went smoothly.

When you started Green Mosul, what did you hope the outcome would be?

To be honest, when we started, I had fears it would not succeed. Given the gravity of what had happened in the city, I was concerned people might not be interested. But we started Green Mosul with three goals. One was that we would create a sense of responsibility among the people. Many had become disconnected from the city as a result of what had happened since 2003, and we wanted to reintroduce a sense of responsibility among citizens to contribute to their city. Our second aim was to introduce a mechanism of communication between communities that wasn’t about religion or ethnicity. The third was to create trust between the government and the public. I still make sure I communicate everything I do with the government, and then I communicate this to the public. I wanted to reintroduce the meaning of governance. I wanted the public to know the government is not just people sitting behind closed doors, but that they themselves can gain access to them and work with them.

We’ve achieved those three things, but we’ve also created friendships between different communities. They still visit each other, they are friends with each other, and they are still communicating. These different communities are working together, and that’s what we aimed to do, and we succeeded. I’m so happy about the results. I’m so happy about the involvement of the community. I’m so happy that we were able to do this in a complicated context, where people are still healing. This means there is potential for people to work together in Mosul to create a sustainable future for themselves, but it will take time.

The other element we introduced is that we raised awareness about climate change in a very complicated context – imagine talking about climate change in a city that is heavily destroyed and where people are still missing. But Green Mosul succeeded in introducing the conversation around climate change, and the university is now running research and attracting more researchers to work on the subject. One topic which is dear to me is what I call ‘green heritage’. I saw the impact of the destruction of cultural heritage on the people and the potential conflicts that it might create, and I realised that, although Islamic State might not come back, there is another enemy: climate change. It’s important to address this when we speak about preserving cultural heritage. The recovery of Mosul’s cultural heritage plays an important role in the collective healing from generational trauma, and it gives hope to the people that social cohesion is still possible as well as limiting the impact of radicalisation.

It sounds like Green Mosul has been a great success. How important do you think it is to have grassroots-led vs authority-led initiatives in Mosul?

I think encouraging the grassroots to lead more initiatives is fundamental for a healthy rehabilitation of Mosul, because not all recovery efforts succeed in meeting the results they intend. A quick rehabilitation might bring the opposite outcomes, so it’s important to create a sense of responsibility among the grassroots so they feel they have a say in what’s happening. Now is the right time to work on this, and invest in this, because we are still in the process of rebuilding and healing. It’s the best time frame we have to enable people to develop this sense of responsibility.

At the same time, we shouldn’t ignore the government. The government can always contribute, and opportunities can always be created if there’s a will, a sense of responsibility, and most importantly, diplomatic expertise – because it’s all about how you communicate your ideas in a post-conflict environment.

In Mosul, we need less focus on religion. When rehabilitation efforts target certain religious groups, they’re not talking about justice for all. They’re just reinforcing divisions. Create the space, and let people be the way they want. I think let’s talk more about trees than religion. You can plant trees in a mosque or in a church, but it doesn’t have to be because they’re a mosque or a church. It can be because you care about the environment or because you simply want to enjoy green space.

You can read more about XCEPT’s research on reconciliation initiatives in Iraq here: Iraqi heritage restoration, grassroots interventions and post-conflict recovery: reflections from Mosul

Bangladesh is facing a climate emergency. Although it is one of the world’s least polluting nations, it is already experiencing some of the most severe effects of changing weather patterns. The country lies close to sea level, and much of the land is river delta that is prone to seasonal flooding, erosion, and salinity intrusion and faces the risk of devastating cyclones, all of which can be catastrophic for local communities and their livelihoods. Many families are unable to recover from such climate disasters and are forced to move to other parts of Bangladesh or across borders to rebuild their lives.

Unsurprisingly, Bangladesh has become a prominent voice in global conversations about climate change and the need for international responsibility-sharing. Developing nations generally shoulder an outsized share of the costs of climate change compared to wealthier nations, a fact recently recognised in global forums such as the United Nations Climate Change Conference, which convenes the annual Conference of Parties, or COP. In its 27th sitting, in 2022, the COP established a loss and damage fund for vulnerable countries, which was operationalized a year later at COP 28. While proponents celebrated this as a win, many practical challenges remain, including raising sufficient funds and figuring out how to measure losses and distribute resources equitably among nations. The many intersecting consequences of environmental degradation require long-term solutions and a holistic approach. Mechanisms like the loss and damage fund will not increase climate resilience if social, political, and economic factors are not considered alongside the environmental ones. Migration and displacement of affected populations is one of the most significant consequences of climate change. Along with the downstream impacts on labor markets, social networks, and transnational relationships, these will need to be accounted for in national and international climate strategies and development policies.

As “ground zero” for a shifting climate that is turning many environments inhospitable, Bangladesh offers a case study of these overlapping vulnerabilities. In parts of the borderlands with India, longstanding social and political fragilities lie beneath the new environmental stressors. The border itself has been an historical point of contention between the two countries, and security measures in the past have led to violence. The distance from central governance institutions in Dhaka can result in border regions being underrepresented in national climate strategies, including the distribution of resources, which can further marginalize ethnic and religious minorities within border communities. The risks from climate change in such areas of existing vulnerability cannot be overstated: economic instability, food insecurity, unreliable access to justice, and increased inequalities that can trigger communal violence.

Attempts to institutionalise sustainable solutions in climate-vulnerable areas must be rooted in a situated understanding of how communities experience and respond to environmental disruptions. Outsiders may struggle to grasp these nuances, which can lead to poor planning and interventions that cause further harm. In southwestern Bangladesh, for example, seasonal and informal migration to urban centers in India have become more and more of a survival mechanism for those who have lost their agricultural livelihoods. This can clash with policies that regulate cross-border movement, including the steady increase in border fencing. Researchers and practitioners working in affected areas can play an important role in collecting information and building evidence that speaks to local experiences, but this must be done with sensitivity and recognition of the power dynamics of classical research settings. Historically, the study of vulnerable populations in particular has been steeped in inequality and defined by an essentially extractive relationship between researchers and researched.

As the world mobilises to support climate adaptation and resilience, decision-makers need analysis that reflects the needs and priorities of communities at the forefront of climate change. The Asia Foundation is working with the Centre for Peace & Justice (CPJ) of BRAC University in Bangladesh to develop a framework for assessing how existing drivers of fragility interact with the onset of climate change, in order to understand the risks for future climate resilience and development programming in the country. The Foundation’s partnership with CPJ originates in the UK-funded development research program XCEPT, Cross-Border Conflict: Evidence, Policy, and Trends, which works with local researchers to provide analysis of conflicts in border regions that is grounded in the affected communities.

With support from this program, CPJ has developed a new methodology for community-driven data collection, based on “participatory research,” that seeks to avoid the vertical power dynamics inherent in traditional research models. CPJ first employed this methodology among the Rohingya refugees seeking asylum in the Bangladeshi coastal town of Cox’s Bazar, on the border with Myanmar. A network of researchers drawn from within the refugee community itself enabled the affected population to become co-producers of knowledge and solutions, building trust between aid providers and recipients and strengthening the credibility of the research findings. The insights this yielded have helped foreign donors and humanitarian agencies operating in the world’s biggest refugee camp to work more effectively. This approach is a major contribution to localising aid, as it shifts power over information towards the affected populations.

This year, CPJ is piloting the same research approach in southwestern Bangladesh, applying it to the question of how climate adaptation strategies reflect and respond to broader social and political fragilities in the local context. A scoping study first undertaken by the team in 2022 determined that this question is a major factor in the long-term success of such strategies. Subsequently, a research project was designed replicating the approach used in Cox’s Bazar, starting with the recruitment and training of young people to work as “community researchers.”

The team faced some initial challenges: refugee camps are an entirely different operational context than areas of the general population, because of the institutional control within the camps and the relative immobility of the camp population. Furthermore, the severity of the refugee crisis in Cox’s Bazar was a powerful motivator for camp residents to participate. In southwestern Bangladesh, on the other hand, researchers wondered how to build interest among local youth in participating in the data collection and how to encourage respondents to open up about their experiences and aspirations. Researchers have also reflected that the obstacles facing Rohingya refugees in their fenced camps are immediate and tangible, while slow-onset climate factors that distress and uproot communities in climate-affected border towns are less immediately apparent.

To apply a proven methodology in a completely new context, both major and seemingly minor aspects of the research study may need to be revised. CPJ’s community-based research approach acknowledges the complexity and unique social order of the borderlands, allowing for a more comprehensive understanding of the study sites. Climate realities around the world are not equal. These locally grounded methods of exploration avoid the mistakes of knowledge systems that force top-down assumptions on local communities, and instead empower them to be the voices of their own experience.

The initial phase of this new project is nearing completion, and community researchers are receiving training for the first round of data collection. From where we stand now, there is much to discover, to learn, and to unlearn, and we hope to do it together.

Tabea Campbell Pauli is a senior program officer with The Asia Foundation’s XCEPT program, and Tasnia Khandaker Prova is a research associate with the Centre for Peace and Justice of BRAC University. They can be reached at [email protected] and [email protected], respectively. The views and opinions expressed here are those of the authors, not those of The Asia Foundation.

Syria’s south is caught precariously between two realities. On one side, there is Israel’s resolute campaign to neutralize border threats, particularly after the traumatic Hamas attack of October 7 last year. On the other, there is Iran’s growing entrenchment in Syria’s southern border regions, especially Quneitra Governorate, which is aimed at securing geopolitical leverage in the region. Unless there is a significant change in the current status quo, there could be a military escalation down the road that again undermines regional stability.

Looking at southern Syria after Syrian government forces returned to the region in 2018, one can’t help but notice an irony. The deployment of the army and security forces was largely premised on an understanding among Russia, the United States, Israel, Jordan, and the Assad regime in Damascus allowing for their return, but on the condition that Iran and its allies would not return with them. Moscow was to guarantee the arrangement. However, today what we are seeing, instead, is a contest for domination of the south in which Iran has accumulated power while Russia and the Assad regime have lost ground.

The war in Ukraine, which has compelled Moscow to reallocate its resources and refocus its energies, has been the main cause for the relative decline of Russian sway. Russia had a multifaceted presence in Syria. It played the role of active combatant, with personnel on the ground; it had an influential diplomatic role in negotiations to resolve the Syrian conflict; and it played a unique intermediary role, brokering agreements among stakeholders who otherwise had no direct communication with each other, which enhanced its leverage.

The agreement to return government forces to the south in 2018 was a byproduct of this unique position. Yet since then, Israel and Iran have exploited the erosion of Moscow’s influence. At the same time, there has also been a continious decline in the strength of the Assad regime. This has resulted from a combination of factors, including U.S. sanctions, Syria’s continued isolation at the regional level, and the systematic breakdown of the Syrian state as a consequence of the uprising.

The outcome of this disastrous situation has been visible both economically and politically. For example, the Syrian pound was valued at SP3,600 to the U.S. dollar on the day Russia began its offensive in Ukraine, and now it hovers just below SP14,000—a depreciation of approximately 290 percent. Another sign comes from Suwayda, where the Druze community—historically not aligned with the opposition—has been staging continuous protests against the regime since August 2023 for failing to provide security, stability, and basic services, among other things. The authorities have not been able to quell these protests. Meanwhile Arab countries, chiefly Jordan, are also concerned about developments in the south, but have little ability to influence the course of events there.

Though Iranian influence may be rising, Tehran does not exercise control over the south, while facing numerous obstacles there. Israeli opposition is the most significant. Israel has continiously targeted Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps and Hezbollah officials since 2013, with more than 240 strikes across Syria. Iran has also faced local pushback. In Daraa and Suwayda Governorates, the population is largely hostile to the Iranians, who have progressed in a limited way in these areas. Data collected by the author on Israeli airstrikes between 2013 and February 2024 show that Daraa and Suwayda were targeted far less frequently—only seven times—than the hundred or so times Rural Damascus Governorate was targeted. This indicates that Israel doesn’t consider Daraa and Suwayda to be substantial threats.

But Iran has had some successes as well, namely in the highlands of Quneitra that remain under Syrian control and overlook the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights. Iran and its allies have been able to consolidate their position in this region. Geographically, its rugged, mountainous terrain allows for concealment, facilitating militia operations and movement. Quneitra’s proximity to the Lebanese border, which is under Hezbollah control, and southern Rural Damascus Governorate, where Iranian influence is pronounced, has further confirmed the broader region as a nexus of Iranian-aligned activity.

In addition to this, local dynamics in Quneitra during the Syrian uprising created openings for Iran and its allies. Between 2015 and 2018, the Sunni extremist group Jabhat al-Nusra controlled the area and threatened the small Druze and Christian populations. In response, these communities forged ties with Iran and, especially, Hezbollah for protection, allowing the Iranians to retain a foothold on the Quneitra front throughout Syria’s conflict. That is likely why, since 2013, Quneitra has been the second most frequent target of Israeli strikes, being hit 30 times.

What gives a strategic edge to Iran in the south is the disorder that followed the return of government forces in 2018. The security situation has remained precarious and there is a growing illicit economy, both of which have created an environment conducive to the expansion of Iranian influence. Iran’s experience in operating in such settings in the Middle East is unparalleled. In principle, the Assad regime and its institutions should have had the advantage, given their local knowledge. However, they are resourceless, have lost the mechanisms of control they had before 2011, and are now greatly dependent on Iran.

Interestingly, after the start of the Gaza war last year, Russia stepped up its presence along the Golan Heights by establishing several observation posts. This presence could increase pressure on Iran or help mitigate an Iranian-Israeli confrontation in southern Syria, even if Moscow cannot replace or undo Iranian influence. Russia is not only dependent on Iran because of the Russian war in Ukraine, it has also failed to create a strong network of local proxies tied with patronage networks like Iran has done. Therefore, if Iran continues to reinforce itself near the occupied Golan, or deploys more weaponry there, a conflict with Israel may become inevitable.

This article was originally published on Diwan, hosted by the Malcolm H. Kerr Carnegie Middle East Center.

Since 2011, the conflict in Syria has transformed the country’s border areas. In most of these, Syrian sovereignty is now contested to varying degrees among local, national, and regional actors. These dynamics have led to a situation in which a variety of political centers (other than Damascus) have come to exercise influence over borders. Though there are stark differences among these border regions, they all have in common the fact that they are entities outside Damascus’ control, each with its own economy, security, and even ideology—effectively, de facto cantons.

Controlling Syria’s borders has always been a central aspect of the Assad regime’s power. However, given its loss of influence over many of its borders—added to its merely tentative authority over those border areas controlled by allies—what we are seeing today in the country is a significant long-term transformation in the way Damascus operates. It is unlikely that the regime will restore state sovereignty over these border areas anytime soon. Rather, in the coming years developments there are likely to be determined by local and regional actors, and the interactions between them.

Multiple variables will affect the outcome of these interactions. These can be placed into three broad categories: demographics, or more specifically the fate of the displaced and refugees; markets, or what might be called cross-border economic relations; and security. Given the likelihood that Damascus will be unable to restore full control over its border regions, the question is whether efforts to resolve the Syrian conflict should not encompass a wider range of local and regional actors, while also focusing on demographics, markets, and security? Such questions are what a group of Carnegie scholars hope to address in a forthcoming paper.

The movement of people has played a major role in border regions, notably the north. But these trends have also been characterized by a paradox. The regime has pursued a policy of reducing hostile populations under its control by allowing for the creation of large areas where it has a limited presence, or none at all—such as Idlib Governorate near the Turkish border. But this has also undermined the state’s sovereignty over these territories. Northeastern Syria, where the regime has allowed an entire segment of its population, namely the Kurds, to create a self-governing entity is equally representative of such an approach.

As cross-border markets and economic ties have developed, they have transformed, and in some cases even replaced, prewar market relationships in particular areas. Control over such relationships had also constituted a major factor in the Syrian state’s power before the conflict. New economic ties, as seen in the town of Sarmada, for instance, have tied border regions more closely to Türkiye than to Damascus. This development represents another aspect of the deterioration in Syrian state sovereignty over these areas.

Security, however, remains the main issue that will shape the future of Syria’s conflict in the country’s border regions. Over the last decade or so, Syria has seen the emergence of a number of parallel security orders—Turkish, Iranian, and American—each within specific geographical zones of operation and influence. While these may differ from each other, they too have all greatly eroded the sovereignty of the Syrian state and regime.

The Turkish security order has established effective self-defense zones and reshaped local power structures in parts of the north where the Turkish military has a presence. The more fluid Iranian model has connected Iraq to eastern and southern Syria and Lebanon through the promotion of local, pro-Tehran militias. The example of the crossing with Iraq has shown how Iran uses such passageways for its militias, allowing it to exert regional influence, even as it expands its sway over armed Arab tribal groups in the area. The United States also has a presence in eastern and northeastern Syria, as well as in the Tanf base near Jordan, which began as part of American participation in the coalition to fight the Islamic State group. For the foreseeable future, Damascus’ ability to restore its sovereignty in all these border locations will be virtually nonexistent.

The conflict in Syria has completely destroyed the country’s national framework, with local-regional having risen on its ruins. These ties have expressed themselves across all of Syria’s borders. The established approaches to resolving the crisis are therefore no longer useful today. The Geneva process, which assumed a political transition would take place within a Syrian national framework, is unrealistic. Not even the local deals that emanated from the security-focused Astana process between Iran, Russia, and Türkiye are effective. Neither takes into account the radical transformations that have shaped Syria’s political, social, and security structures since the war began. Until a new approach is tried, one that includes an effective local element within new regional equations, Syria will remain in limbo, at the expense of both its sovereignty and a society devastated by war.

This article was originally published on Diwan, hosted by the Malcolm H. Kerr Carnegie Middle East Center.

Harith Hasan is a nonresident senior fellow at the Malcolm H. Kerr Carnegie Middle East Center, and a resercher at the Arab Center for Research and Policy Studies. His research focuses on Iraq, sectarianism, identity politics, religious actors, and state-society relations. He has just published a paper at Carnegie, titled “Iraq’s Development Road: Geopolitics, Rentierism, and Border Connectivity,” on the Iraqi project to build a port, road, and railway infrastructure in Iraq to connect the Persian Gulf to Türkiye and beyond. It is to discuss his paper, and the broader regional implications of the Development Road, in a context of growing regional competition, that Diwan interviewed Hasan in early March.

Michael Young: You’ve just published a paper at Carnegie on Iraq’s Development Road project. Why did you choose this topic and what do you argue?

Harith Hasan: This topic is important for two reasons. First, there is growing interest, both in the region and globally, in developing new routes for cross-border international trade, to the point where the Middle East today is an arena for geoeconomic competition between China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and counter projects supported by the United States, including the India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor, which recently gained prominence in light of the Gaza war and Ansar Allah’s attacks on commercial vessels in the Red Sea. In this context, interstate and interregional trade corridors are increasingly intertwined with geopolitical alignments.

Second, Iraq, like several countries in the region such as Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and other Gulf states, is witnessing a shift in interest toward megaprojects and cross-border trade. After years of ethnic and sectarian divisions, the ruling elite is trying to look for new sources of legitimation, and here the idea of “development” is back again in the national discourse, but in a different way from the period of populist, socialist developmentalism during the 1960s and 1970s. The new model is more inclined toward open markets, integration into the global economy, and the expansion of service sectors. The Development Road is also tied to what has finally become a widespread belief that Iraq needs to diversify its economy and sources of income away from a complete reliance on oil revenues.

MY: What are the main obstacles to the project inside Iraq, and outside? In your judgment, given these obstacles, what are the chances that the project will be implemented?

HH: There are many obstacles to the fulfillment of the Development Road that suggest Iraqi ambitions may be inflated. These include rampant corruption, mismanagement, and the attempts of ruling groups to capture the state and its resources in ways that fragment state institutions and inhibit the government’s ability to orchestrate smooth planning and implementation. Also, the factional nature of Iraqi politics and the country’s frequent fluctuations facilitate short-term calculations, which tend to sideline long-term projects.

Even with Iraq receiving $8–9 billion per month from oil exports today, thanks to the rise in oil prices, there are doubts about the state’s ability to finance and implement such a megaproject, especially given the level of corruption prevailing nationally and the direction of resources to finance an ever-larger public sector and public subsidies. The obstacles also are tied to the potential for insecurity and instability in Iraq, which could chase away investors or countries seeking to benefit from the Development Road. And, perhaps most important, Iraq will have to find a place for itself in the midst of regional geoeconomic and geopolitical rivalries, as competing trade connectivity projects are being put forward. These include, as I noted earlier, China’s BRI, the India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor, as well as Iran’s ambitions to become a platform for transregional trade.

MY: How likely are leading Gulf states to support Iraq in ensuring the Development Road project succeeds, particularly given Iran’s considerable influence over Iraq? Which Gulf states are more likely to help in this regard, and why?

HH: Currently, Qatar seems to be the main Gulf state interested in helping to advance the project, partly due its dire experiences during the blockade imposed on it by Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), and Bahrain in 2017–2021, which led the Qatari leadership to consider alternative routes for trade. Also, Qatar has strong ties with Türkiye, its main regional ally before and during the blockade. Türkiye supports the Development Road enthusiastically because it serves as a shortcut to the Gulf and meets Ankara’s ambition of being a hub for global trade connections.

The UAE is also a potential partner, especially as Iraqi Prime Minister Mohammed Shia al-Sudani has sought its help in managing the Faw port, which represents the cornerstone of the project. This could work well with the UAE’s interest in expanding its presence in Iraq and sustaining its status as a key global player in managing or controlling ports. However, the UAE may also be less inclined to participate in the project because of the potential of Faw port to become a rival of its own ports, and because of the influence of Iran-allied armed groups in Iraq that are hostile to the UAE. More importantly, given the attention surrounding the India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor during the Gaza war and the possibility of a second Trump administration in the United States, the UAE may prefer to wait before committing to such project.

Finally, Kuwait considers the Faw port to be a competitor of the Mubarak al-Kabeer Port it is building on Boubiyan Island, whose construction sparked tension between Iraq and Kuwait. Some of this was related to the maritime borders dispute between the two countries, but it was also due to Iraq’s view that the Mubarak al-Kabeer Port would harm the prospects of the Faw port. These disputes led to the suspension of work at the Kuwaiti port for a time, but in July 2023 the government announced a resumption of work there.

MY: The Development Road comes at a time when China is pushing its Belt and Road Initiative. In what way are the two projects contradictory or complementary, particularly as Iraq was a major recipient of Chinese funds allocated to the BRI?

HH: Iraq’s place in the BRI has raised major questions at home, where observers and activists have wondered whether the Development Road is linked to, or separate from, Beijing’s aspirations. In 2021, Iraq emerged as the largest beneficiary of Chinese allocations to the BRI, receiving $10.5 billion out of a total of about $60 billion. Before that, Adel Abdul Mahdi’s government had agreed with China to establish a joint fund in which the value of 100,000 exported Iraqi barrels of oil per day would be used to pay for Chinese loans and investments in reconstruction and development projects in Iraq. Indeed, the “turn toward China” has become part of the political rhetoric of some Iraqi political factions, especially those close to Iran, which have presented this as a means of confronting U.S. hegemony.

However, in practice, Iraq does not occupy a key position in Chinese plans to benefit from regional connectivity projects. Beijing’s widely proposed land route passes through Central Asia and Türkiye, not through Iraq. Therefore, the Iraqi government has portrayed the Faw port as a complementary project, providing a new sea route that can also serve China and emerging economic powers in Asia, presumably shortening the time period, and costs, of trade with Europe. But even here, Iraq faces fierce competition from neighboring countries. Some of them are more established in international trade, port management, and shipping, such as the UAE, and some of them have the ability to disrupt Iraq’s plans to implement the Development Road, such as Türkiye, Iran, and Kuwait.

MY: How do you think such transnational infrastructure and connectivity initiatives will affect Middle Eastern borders in the future? Will they turn border areas into zones of collaboration, or will they lead to heightened competition between states?

HH: The fact that rival geoeconomic connection projects are being put forward in the Persian Gulf and broader Middle East suggests that, instead of achieving their stated goal of promoting economic integration and cooperation, these projects may in fact exacerbate political antagonisms. Iraq has a long history of border disputes with most of its neighbors, and in Iran’s and Kuwait’s case these have triggered wars and invasions. Therefore, efforts to increase the economic value of border zones through new ports and road networks could aggravate latent tensions and lead to further conflicts. That may be another reason why the great aspirations surrounding the Development Road might never be met.

This article was originally published on Diwan, hosted by the Malcolm H. Kerr Carnegie Middle East Center.

Research supported by The Asia Foundation illustrates how Chin State, on the country’s northwestern border with India, is both a center and a broader microcosm of today’s resistance. Home to half a million people, and with historically strong tribal diversity, Chin State has suffered throughout the years of violence and instability that affected much of Myanmar as the country’s military struggled to impose central rule. The result has been persistent underdevelopment, and many people have left Chin State, often as refugees. They now constitute a substantial diaspora regionally and in countries of the Global North.

Violent crackdowns on the peaceful protests that sprang up immediately after the 2021 coup led many previous noncombatants to take up arms to defend themselves. Tensions grew rapidly as dozens of new, local resistance groups emerged, many known collectively as Chinland Defense Forces. The Chin National Front, an armed group with a long history of resisting Myanmar’s central authorities, which had been closely involved in peacebuilding efforts over the last decade, gained significant popular support.

These armed groups made significant gains in 2023, taking control of resources, territory, roads, and infrastructure in both urban and rural areas. Mirroring the successes of fighters across the country, both the new Chin resistance forces and established armed organizations have pushed back against the military, reportedly capturing 12 military bases and liberating five towns in the last year.

With parts of the country suffering internet blackouts, and information on social media unreliable, it is difficult to grasp a complete picture of the trajectory of the conflict, particularly for observers outside of the country. Airstrikes and arson attacks by Myanmar forces have led to hundreds of deaths and driven tens of thousands of Chin civilians from their homes and livelihoods. The United Nations estimates that more than 60,000 people have fled to the Indian border states of Mizoram and Manipur, while another 61,000 remain internally displaced. Chin humanitarian organizations estimate that the real figures are much higher. Camps for the internally displaced are increasingly insecure as the conflict drags on and resources dwindle, but heavy fighting and the remoteness of the region pose a major challenge for aid and support.

The principal humanitarian response has come from Mizoram, which is estimated to have received more than 5,000 refugees from Chin State in 2023 alone. Refugees in Mizoram have some access to healthcare and children’s education, thanks to a long tradition of cross-border kinship.

As the crisis in Myanmar competes for global attention, international support has diminished. In the meantime, the Chin diaspora, reaching from the border regions of India to communities across Asia, Europe, the United States, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand, has mobilized to provide financial and material aid to refugees and those who remain in Myanmar. Local humanitarian responders estimate that up to 90 percent of the funds they receive come from Chin groups overseas, though this support is often distributed on the basis of local or subethnic ties that can result in unequal access.

These developments underscore the central role of Myanmar’s borderlands. Distant from the historical control of the central authorities, these porous, peripheral zones are crucial for the safe passage of refugees, for aid to the internally displaced, and for support of the organized resistance. Border communities in India have set up camps, provided essential services, and even extended financial support to refugees from Chin State. The continued movement of people and goods is critical to maintaining safe havens and humanitarian support for civilians.

Myriad forces are at play today in Myanmar’s resistance. The local roots of the resistance movement have produced a diverse array of actors with different agendas and approaches, and building a united front is challenging. The divergence of approaches and visions among the political leadership and the multitude of armed groups adds a further layer of complexity, as politicians point to their pre-coup electoral mandates, while armed groups cite strong public support. On the ground, communities also hold uncertain views about who is in charge.

Multiple councils and coordinating bodies have emerged from the Chin opposition. Efforts initially focused on the Interim Chin National Consultative Council as a liaison between state actors and the rest of Myanmar’s resistance network, but internal disagreements between a few powerful actors led to a split in early 2023. Subsequently, the rival Chinland Council was created, which has garnered greater support among key resistance forces as well as the public, likely the most crucial factor in its legitimacy as the state’s leading political body. The immediate need is to create a functioning state government and establish statewide systems for public administration and the provision of essential services.

As nonstate forces in Chin State and across Myanmar continue to resist the military’s attempts to impose its central rule, communities caught up in the conflict face severe consequences. International support for civilians is crucial, particularly for the most vulnerable, who have lost homes and livelihoods through violence and displacement. In the immediate term, humanitarian actors can connect with existing local and diaspora networks in the border region to increase the reach and effectiveness of aid distribution. Looking to the future, in Chin State as in other parts of Myanmar, effective investments in peace will hinge on the continuing dialogue between communities and resistance leaders to find common ground for future governance.

Tabea Campbell Pauli is a senior program officer for The Asia Foundation’s Conflict and Fragility Unit. She can be reached at [email protected]. June N.S. is an independent researcher whose latest report, Resistance and the Cost of the Coup in Chin State, Myanmar, is the principal source of this story. The views and opinions expressed here are those of the authors, not those of The Asia Foundation.

Content warning: contains mention of sexual violence and suicide.

Almost two years have passed since Russia invaded Ukraine, and mental health is high on the agenda for the Ukrainian government. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates approximately 9.6 million people in Ukraine may have a mental health condition as a result of exposure to conflict, while Ukraine’s Ministry of Health expects 15 million people will require psychological support to manage mental health problems caused by the war.[i]

Spearheaded by Ukraine’s First Lady, Olena Zelenska, a National Program of Mental Health and Psychosocial Support (MHPSS) aims to provide affordable and effective mental health services for anyone who wishes to use them, while a campaign launched in March 2023 encouraged Ukrainians to look out for each other’s mental wellbeing.[ii] The summit at which President Zelensky made his comments was organised under the theme ‘Mental Health: Fragility and Resilience of the Future’.[iii]

Ukraine has a big task on its hands, and it’s not alone. Around the world, populations in countries affected by conflict are vulnerable to experiences of trauma and its various manifestations. In 2019, the WHO estimated that one in five people living in a conflict zone experience some form of trauma symptom, such as PTSD, depression, anxiety, or sleeping disorders. In Gaza, it is estimated that 97.5 percent of 10 to 19-year-olds suffer from PTSD, and this will rise acutely in response to the current conflict.[iv]

Humanitarian aid to help deliver psychosocial support (PSS) is both welcome and necessary. Yet, recent research carried out by the Cross-Border Conflict Evidence, Policy and Trends (XCEPT) research programme suggests that, when it comes to addressing conflict-related trauma, men and boys are often overlooked. Not only does this have an impact on the wellbeing of affected individuals, but research suggests that addressing conflict-related trauma amongst men is also vital for prevention of continued insecurity and conflict transformation more broadly.[v]

Overlooking men in humanitarian responses

In a conflict setting, men and boys are affected by direct violence.[vi] They are most at risk of death by violence or summary execution. They are more likely to be imprisoned or disappeared. They suffer beatings and torture due to gender norms which assume them to be the protectors and leaders of a community, rendering them targets of violence. They also experience conflict-related sexual violence (CRSV) to a much greater extent than was previously assumed.[vii]

Yet, male victims are underrepresented in PSS services delivered by humanitarian organisations.[viii] A study for XCEPT of 12 INGOs and NGOs operating in Syria, Iraq and South Sudan found that only two of the organisations operated PSS programmes targeted at conflict-affected men.[ix] These were a trauma awareness training programme run by Catholic Relief Services (CRS) in South Sudan and a programme of psychoeducation workshops run by Relief International (RI) in northern Syria.

Although international organisations, such as the United Nations Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC), have made commitments to focusing on gender-related needs in their humanitarian work, for many this equates simply to focusing on women and children.[x] Common stereotypes surrounding gender reinforce the idea that men are primarily the perpetrators, or that they may not need help coping with traumas.[xi] This means that, while there are already insufficient resources dedicated to helping women and girls, there are even less for men.

Such gendered assumptions around the incompatibility of masculinity and vulnerability permeate academic and policy circles, but it is important to note that this is not clear cut. There is a noticeable imbalance in attention paid to manifestations of PTSD amongst Western servicemen, versus the very limited recognition of trauma experienced by civilian men in FCAS.[xii] These inconsistencies raise questions around how stereotypes of masculinity also intersect with race or other identity markers.

The costs of failing to act

Gendered expectations may result in a lack of attention being paid to conflict-related trauma in men and boys, but such norms also impact on the way trauma is experienced. For example, where men are often assumed to be the defenders and protectors of family or society, becoming unable to safeguard family may perpetuate a sense of trauma-associated stress. Similarly, when men are unable to fulfil masculine expectations of being the provider, this again can impact on a sense of wellbeing, that may manifest in negative ways.[xiii]

Recent XCEPT research on the experiences of ex-military Syrian refugees in Turkey found that, for many, practical concerns about being able to provide for their families were a cause of anxiety, leading them to exist in unstable ‘disturbing’ situations.[xiv] A representative from an organisation based in Syria also noted that such situations exacerbated suicidal tendencies:

‘Where the men are sitting at home, or looking for a job, and women are the only providers for the family … in mental health terms, this has become one of the stressors for men – that they cannot provide the needed help for the family or children. Actually, it’s one of the suicide situations [amongst men] in this area.’[xv]

Masculine expectations can also cause men to employ maladaptive coping behaviours, such as risk-taking, withdrawal, or self-harm. Such behaviour can be attributed to a desire to avoid ‘displays of emotional distress, which would be discordant with, and threatening to, masculine identity and performance’.[xvi] Men can therefore be less inclined to seek, or accept, help and support, a choice which increases the risk of developing negative coping mechanisms.[xvii] Concerns about stigma are not unfounded. One study on the survivors of male sexual violence in Northern Uganda found that many were refused help as it wasn’t believed men could have been victims of CRSV.[xviii]

Without receiving proper support, male responses to trauma may develop into a normalisation of violence as a coping strategy. In extreme cases, this can lead to appetitive aggression, whereby an individual gains a sense of pleasure out of violence, which could be a way of buffering the development of PTSD symptoms.[xix] Research has found that, in the aftermath of violent conflict, domestic violence tends to rise when former fighters return home. Community violence can also increase as a result of PTSD symptoms and appetitive aggression.[xx]

Addressing conflict-related trauma in men and boys thus benefits not just their own wellbeing, but the wellbeing of their families and the wider community. After taking part in the programme run by CRS in South Sudan, participants reported benefits such as being able to control stress and channel anger in ways which avoided self-destructive behaviour or lashing out at family members.[xxi]

Addressing conflict-related trauma amongst men

Research carried out by XCEPT highlighted four key points to guide the delivery of PSS programmes for men and boys. In situations where there is limited access to basic needs, these programmes are inevitably deprioritised. This is where using innovative and integrative programming can be beneficial. Such programmes may involve mainstreaming PSS interventions into broader livelihood programmes and context-specific services, which encourages participation and complements efforts to cater to primary needs.

Programmes should also be designed through a culturally sensitive masculinity lens to ensure uptake. This includes using neutral terminology to avoid stigma surrounding mental health; respecting societal norms by scheduling sessions to work around employment commitments or livelihood activities; and considering under what circumstances it is appropriate to host group or individualised programming. For example, for LGBTQI+ men, or in instances where men have suffered sexual violence, individual, confidential sessions reduce risk to the individual, whereas group workshops may be more beneficial for psychoeducation programmes that benefit from peer-to-peer support mechanisms.

Moral injury, the impact of carrying out an action that transgresses an individual’s ethical or moral standards, is often side-lined in PSS programming due to its association with perpetrators of violence. In some situations, engaging with moral injury-induced trauma can be beneficial, as it allows individuals to deal with feelings of anger, which may otherwise find an outlet in the perpetration of violence in the community.

Importantly, local communities should also be engaged in programme design to ensure services are context appropriate. In the programme run by RI, for example, a scoping exercise was initially carried out to establish themes men wanted to focus on. The themes selected tended to revolve around stress and anger management, for which family members then reported ‘good results’ among participants who had been working on these issues. Involving local communities can also help increase the sense of ownership and legitimacy amongst participants, which encourages attendance and engagement.

Although men are often on the frontline of conflict, they are also often overlooked in humanitarian responses to trauma. This affects their individual wellbeing, and the wellbeing and security of wider society, which may bear the burden of maladaptive coping behaviours caused by unaddressed trauma. To make sure PSS efforts succeed, it is important they take the cultural context and local needs into account. While an increase in focus and resources on conflict-related trauma amongst men is important as a matter of both wellbeing and conflict prevention, it remains crucial that this should not lead to the diversion of services away from women and girls, which also continue to be insufficient and under-resourced.

This blog was originally published by the International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation.

[i] https://www.economist.com/europe/2022/08/06/ukraine-is-on-the-edge-of-nervous-breakdown

[ii] https://www.president.gov.ua/en/news/olena-zelenska-rozpovila-yak-vtilyuyetsya-iniciativa-zi-stvo-80109

[iii] https://www.president.gov.ua/en/news/olena-zelenska-na-yes-2023-mentalne-zdorovya-osnova-stijkost-85541

[iv] FARAH HEIBA, Mental health in Middle East conflict zones: How are people dealing with psychological fallout? https://www.arabnews.com/node/1894521/middle-east

[v] Heidi Riley, Men and Psychosocial Support Services Programming, XCEPT, 2023. https://icsr.info/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/XCEPT-Briefing-Note-Men-and-PSS-programming.pdf

[vi] KREFT, ANNE-KATHRIN; AGERBERG, MATTIAS. Imperfect Victims? Civilian Men, Vulnerability, and Policy Preferences, 2023, 1-17.

[vii] Philipp Schulz, “The ‘Ethical Loneliness’ of Male Sexual Violence Survivors in Northern Uganda: Gendered Reflections on Silencing,” International Feminist Journal of Politics 20, no. 4 (2018): 583–601.

[viii] https://pscentre.org/men-dont-cry-a-participatory-workshop-on-mhpss-for-men-and-boys-in-humanitarian-settings/; Brun, Delphine. Men and Boys in Displacement: Assistance and Protection Challenges for Unaccompanied Boys and Men in Refugee Contexts. CARE and Promundo, 2017.

[ix] Heidi Riley, Men and Psychosocial Support Services Programming, XCEPT, 2023. https://icsr.info/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/XCEPT-Briefing-Note-Men-and-PSS-programming.pdf

[x] Gupta, Geeta Rao, Caren Grown, Sara Fewer, Reena Gupta, and Sia Nowrojee. “Beyond Gender Mainstreaming: Transforming Humanitarian Action, Organizations and Culture.” Journal of international humanitarian action 8, no. 1 (2023): 5–5.

[xi] Brun, Delphine. “Why Addressing the Needs of Adolescent Boys and Men Is Essential to an Effective Humanitarian Response.” Apolitical. co. 27 January 2023. https://apolitical.co/solution-articles/en/why-addressing-the-needs-of-adolescent-boys-and-men-is-essential-to-an-effective-humanitarian-response

[xii] Heidi Riley, Men and Psychosocial Support Services Programming, XCEPT, 2023. https://icsr.info/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/XCEPT-Briefing-Note-Men-and-PSS-programming.pdf

[xiii] Brun, Delphine. Men and Boys in Displacement: Assistance and Protection Challenges for Unaccompanied Boys and Men in Refugee Contexts. CARE and Promundo, 2017.

[xiv] Alison Brettle, ICSR, 2023. https://icsr.info/2023/03/29/forgotten-refugees-the-experiences-of-syrian-military-defectors-in-turkey/

[xv] Heidi Riley, Men and Psychosocial Support Services Programming, XCEPT, 2023. https://icsr.info/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/XCEPT-Briefing-Note-Men-and-PSS-programming.pdf

[xvi] O’Loughlin, Julia I., Daniel W. Cox, Carl A. Castro, and John S. Ogrodniczuk. “Disentangling the Individual and Group Effects of Masculinity Ideology on PTSD Treatment.” Counselling psychology quarterly 35, no. 3 (2022): 587–604.

[xvii] Slegh, H., W. Spielberg, and C. Ragonese. Masculinity and Male Trauma: Making the Connections. Washington: Promundo US, 2022.

[xviii] Schulz, 592.

[xix] Slegh, H., W. Spielberg, and C. Ragonese. Masculinity and Male Trauma: Making the Connections. Washington: Promundo US, 2022; Hecker, Tobias, Katharin Hermenau, Anna Maedl, Harald Hinkel, Maggie Schauer, and Thomas Elbert. “Does Perpetrating Violence Damage Mental Health? Differences Between Forcibly Recruited and Voluntary Combatants in DR Congo.” Journal of traumatic stress 26, no. 1 (2013): 142–148.

[xx] Nandi, Corina, Thomas Elbert, Manassé Bambonye, Roland Weierstall, Manfred Reichert, Anja Zeller, and Anselm Crombach. “Predicting Domestic and Community Violence by Soldiers Living in a Conflict Region.” Psychological trauma 9, no. 6 (2017): 663–671.

[xxi] Catholic Relief Services. Strengthening Trauma Awareness and Social Cohesion in Greater Jonglei, South Sudan: A Case Study on the Impact of Social Cohesion Programming. CRS, 2022. https://www.crs.org/our-work-overseas/research-publications/strengtheningtrauma-awareness-and-social-cohesion-greater

In this episode, Caterina Ceccarelli examines what we know about the link between adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and violent extremism, and explores the pathways by which experiencing tough and potentially traumatic events in childhood might turn someone to extremism later in life.

Content warning: This episode contains mentions of sexual violence, self-harm, and suicide.

Dr Heidi Riley and Beth Heron discuss their research into conflict trauma in men and boys, exploring how stigmas and societal expectations can affect the way trauma is experienced, and the dangers to individuals, communities, and wider society if this trauma is left unaddressed.

Offering insights from their in-depth study of two psychosocial support (PSS) programmes delivered by Relief International in Syria and Catholic Relief Services in South Sudan, the pair share what they learned about the way PSS programmes should be designed and funded.

As governments across Europe face the challenge of reintegrating returnees from Iraq and Syria, Dr Joana Cook examines institutional and societal responses to children growing up in violent extremist affiliated families.

Dr Cook talks to Dr Fiona McEwen about the different ways a child’s life can be impacted when a family member is involved in violent extremism, why the narrative of ‘ticking time bombs’ is detrimental to healthy development, and why we need to change the way we engage with these families.

Read more on Joana Cook’s work.