On 8 March, the UN Security Council adopted a UK-drafted resolution calling for an immediate cessation of hostilities in Sudan during the month of Ramadan, a sustainable resolution to the conflict through dialogue, compliance with international humanitarian law and unhindered humanitarian access.

Eleven months into the war, this is the first time that the Council has been able to agree on a resolution. The mandate of the UN Panel of Experts that monitors the sanctions regime in Darfur was also renewed by the Council. Does this signify hope that efforts to end the war might gather momentum? Or is Sudan likely to face a protracted conflict?

The war between the Sudan Armed Forces (SAF) led by General Abdel Fatah Al Burhan and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF) led by General Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo (known as ‘Hemedti’) is a competition for power and resources between rival factions of the regular armed forces.

But it is also rooted in Sudan’s long history of internal conflict, marginalization of the peripheries and lack of accountability for atrocity crimes. Both the SAF’s officer corps and the RSF are creations of former President Omer al-Bashir’s regime.

Each has shown disregard for the lives of Sudanese civilians by waging war in densely populated urban areas. The scale of destruction is unprecedented in Sudan’s modern history.

The conflict has the potential to destabilize already fragile neighbouring countries, create large new migration flows to Europe, and attract extremist groups.

With the world’s attention focused on Gaza and Ukraine, the war receives woefully little high-level political, parliamentary or international media attention, raising serious questions about double standards in dealing with global crises, particularly conflicts in Africa. Sudan is suffering from a humanitarian disaster, with a looming famine and the world’s biggest displacement crisis: 8 million people are newly displaced inside or outside the country, in addition to over 3 million displaced by previous conflicts.

The head of the World Food Programme has warned that the war risks creating the world’s largest hunger crisis. Yet the UN’s Humanitarian Response Plan for Sudan is only 4 per cent funded.

The conflict has the potential to destabilize already fragile neighbouring countries, create large new migration flows to Europe, and attract extremist groups.

Meanwhile, regional actors are fighting a proxy war in the country, giving military, financial and political support to the warring parties. The involvement of Russia and Iran has given the war a geopolitical dimension linked to Putin’s war in Ukraine – partly funded with Sudanese gold – and competition for influence on the Red Sea coast.

Both RSF and SAF forces have used hunger as a weapon of war. The RSF has looted humanitarian warehouses and besieged cities. The SAF-controlled Humanitarian Aid Commission has systematically withheld authorization for crossline movement of life-saving aid to RSF-controlled areas.

Donors will also have to step up to address the spiralling food crisis, by reducing the UN funding gap and supporting grassroots first responders in the Emergency Response Rooms.

One limited outcome from recent international pressure has been the partial reversal of the SAF’s ban on cross-border humanitarian access from Chad into Darfur. The de facto SAF authorities in Port Sudan have agreed to open limited border crossings from Chad and South Sudan. However, MSF International have criticized this as a partial solution at best.

The UN will need to monitor implementation to ensure neutrality in the distribution of aid, while intensifying pressure for unhindered cross-border and crossline humanitarian access.

Donors will also have to step up to address the spiralling food crisis, by reducing the UN funding gap and supporting grassroots first responders in the Emergency Response Rooms.

There is growing pressure for a cessation of hostilities: the fact that the UN Secretary-General, the UN Security Council, the African Union, and the League of Arab States joined forces to call for a Ramadan truce, represents a significant increase in pressure on the warring parties.

Nevertheless, Ramadan has started with further fierce fighting. It is unclear how the Security Council expected a truce to take effect without prior diplomatic engagement to agree an implementation and monitoring mechanism.

Command and control is fragmented on both sides and the warring parties have failed to abide by previous temporary truces negotiated through the Saudi/US-sponsored Jeddah Platform. Concerted diplomacy at the highest level is therefore urgently needed. The aim must be to change the calculations of the generals and counter the influence of hard-line Islamists from the Bashir-era who are blocking negotiations: whether this aim is achievable within the current context remains to be seen.

Standing before members of Israel’s parliament, the Knesset, in 1977, then President of Egypt, Anwar Sadat, declared that a barrier had been built between Israel and the Arab nations: ‘This wall constitutes a psychological barrier between us, a barrier of suspicion, a barrier of rejection; a barrier of fear, of deception, a barrier of hallucination around any action, deed, or decision. A barrier of cautious and erroneous interpretations of all and every event or statement’.[i]

Traditional conflict resolution approaches largely centre on rationality, suggesting that conflicts are mainly driven by conscious intentions and that parties can negotiate a suitable outcome if they rely on logic while advancing their own interests. This approach is necessary, but it fails to adequately acknowledge the role played by unconscious motivations.

As President Sadat recognised, psychological factors can shape conflict dynamics. Logic therefore dictates that conflict resolution efforts must also take these into account. There is an ongoing academic debate advocating for a much-needed analysis of the psychological drivers of conflicts, with key figures such as Mari Fitzduff, John Paul Lederach, Herbert Kelman, and Daniel Kahneman focusing respectively on the role of instincts and emotions in driving societal conflicts; the importance of building relationships and fostering communication to address conflicts; the role of identity in intractable conflicts and the importance of humanising the ‘other’; and the role of cognitive and behavioral psychology in addressing conflicts.[ii]

Among myriad complex factors, unconscious biases can wield significant influence in a conflict, fostering categorisation, alliances, and perpetuating division. Understanding these biases is paramount for understanding the dynamics of conflicts and can provide key information for their mitigation.

What is ‘unconscious bias’?

The concept of unconscious or implicit bias has gradually taken a central space in scholarly, practical, and policy discussions around discrimination and the overall human inclination toward stereotyped behaviours.[iii] The term refers to attitudes or stereotypes that influence our judgments and decisions about people or situations without our awareness. These biases are often rooted in social and cultural factors and can potentially affect our perceptions, actions, and interactions with others.

One of the most popular tools to measure unconscious bias is Banaji and Greenwald’s Implicit Association Test (IAT) which works by asking individuals to sort words, images, or concepts into categories. For example, in a race-related IAT, the terms might be ‘African American’ and ‘European American’, while the categories might be ‘positive’ and ‘negative’. This tool measures implicit biases by assessing the speed of associations, and it is based on the premise that faster responses indicate stronger unconscious associations. It is important to note that the IAT is not without its criticisms and limitations. Critics of the test highlight concerns related to its validity, its accuracy, and its reliability.[iv] Nevertheless, it continues to be widely used as a tool to measure the prevalence of implicit bias in society.

Unraveling unconscious drivers of conflict

Research on unconscious drivers of conflict is still in its infancy, but findings from the field of psychology have shed light on possible avenues for future research. Studies have shown that humans have developed a tendency toward group bonding, which caters to needs such as security and a sense of belonging.[v] Given that bonding implies a certain degree of belonging, we have a tendency to define an in-group, and the construction of this in-group often necessitates the designation of an out-group, which can either be a friend or foe.

Boundaries delimiting the inside from the outside are themselves based on categorisations, whether it be ethnicity, gender, religion, or ideology. These differences can then be mobilised and manipulated by opposing groups in a conflict. While working as a psychiatrist with Vietnam War veterans, Jonathan Shay noted the extent to which ‘Vietnam era military training reflexively imparted the image of the demonized adversary, so inhuman as to not really care if he lives or dies’. As one of the veterans he quotes pointed out, ‘Well, he’s the enemy, ain’t he? You couldn’t kill them if you thought he was just like you’.[vi] One common characterisation of the Vietnamese enemy put forward by the military commanders was that they were ‘enemies of God’, hence morally justifying their deaths.

Evidence of this tendency to see someone else as an ‘other’ has been provided by social psychology experiments such as Muzafer Sherif’s Robbers Cave experiment. In studies like this, fostering awareness of group membership and the existence of competing goals between groups generates hostility. It seems that the existence of categories or the mere act of categorising someone is enough for a division between an ‘us’ and a ‘them’ to arise.[vii]

Discourses shaping the beliefs of certain in-groups during periods of heightened conflict or tension can bear significant responsibility for ensuing violence and the dehumanising attitudes belligerents hold toward one another. Between 1941 and 1945, for example, thousands of civilian Serbs were massacred in Croatia by Ustaše militias, people who had previously been their friends and neighbours.[viii]

The reshaping of perceptions based on group affiliation serves as a driver, intensifier, and justification for violence altogether. It deeply influences perceptions and becomes ingrained to the extent that it solidifies unconscious biases toward the designated ‘other’. In the case of Vietnam, this appeared to serve the function of personal survival and military efficiency, both at the expense of human life.

Addressing unconscious bias in conflict resolution

With an increased understanding of the drivers of conflict comes an increased understanding of how to mitigate it. There are a number of strategies, including awareness-based interventions, individuation, perspective-taking, mindfulness practices, and inter-group contact, which show promise in reducing unconscious bias.[ix] For instance, techniques of individuation, which means encouraging people to view individuals holistically beyond their group identities, can combat stereotypes effectively. When facing death penalty cases, research shows that introducing nuance and presenting the defendant’s life story and challenges can lead to greater success for defence lawyers. In these cases, ‘individuation’ helps overcome jurors’ unconscious bias and stereotypes.[x]

Similarly, perspective-taking strategies, such as being asked to write about or imagine a person’s experience of a particular situation, play a significant role in understanding the impact of biases and promoting empathy. The German mediation program R3solute has attempted to address implicit bias through exercises such as storytelling, in order to foster interpersonal dialogue in the context of heightened social tensions. R3solute notably applied this work to the refugee crisis in Germany by promoting dialogue aimed at deconstructing mutual stereotypes and bias between German citizens and refugees.[xi]

Increasing intergroup contact can, under certain conditions, also contribute to reducing bias by fostering empathy and diminishing fear. Contact theory posits that prejudice between groups can be reduced if members of the groups interact with each other. The organisation Interpeace has acknowledged the significance of this theory in mitigating prejudice and bias in recently-released guidance to help practitioners integrate Mental Health and Psychosocial Support (MHPSS) into peacebuilding efforts. The guidance underscored that identifying a shared goal, advocating for collaboration to achieve it, and reaffirming equal status, especially with the support of authoritative figures, can help dismantle stereotypes through building ‘social cohesion’.[xii]

Conflict resolution approaches that emphasise dialogue, empathy, and comprehension thus align well with strategies to tackle unconscious bias, helping to promote unity and reduce prejudice.

Unintended consequences of unconscious bias interventions

Yet, while there are increasing calls by peacebuilding actors for the use of bias reduction methods in conflict resolution efforts, there is a growing recognition that such interventions have the potential to backfire.

Research suggests that seemingly straightforward interventions, like diversity training – a type of workshop designed to increase awareness and understanding of stereotypes, biases, and their impact – can yield temporary and counterproductive outcomes.[xiii] Such training might reinforce stereotypes by inadvertently validating them. Conversely, interventions focusing on fostering understanding between groups through perspective-taking exercises tend to yield better results than stereotype-centric approaches.

There are also concerns surrounding contact theory, with evidence suggesting that poorly managed intergroup interactions could amplify bias, leading to increased prejudice, anxiety, and avoidance.[xiv] In everyday life, negative intergroup contact may outweigh the benefits of positive contact, a phenomenon known as the ‘contact caveat’.[xv] This phenomenon suggests that the negative impact of such contact on intergroup attitudes is stronger because negative contact increases the salience of group categories, causing individuals to see others as representatives of groups rather than unique individuals. These findings emphasise the need for a more nuanced approach to facilitating these interactions.[xvi]

Research has also found that the efficacy of bias reduction interventions can be influenced by factors such as their scale (individual or systemic intervention) and duration (long-term or short-term). Findings point towards favoring more comprehensive, systemic approaches to bias reduction rather than those targeting individuals. While brief interventions can be effective in the short term, sustained schedules predict greater long-term success. Despite the potential for adverse effects, the current criticisms of implicit bias interventions point researchers and practitioners towards a new direction. As stated by Helen Winter and David Hoffman, ‘the next frontier – measuring the impact of long-term, multi-faceted interventions in the field – has barely begun’.[xvii]

The way forward

It is natural to question why time is being dedicated to exploring an intangible, complex concept that yields conflicting results. Why not prioritise the study of conflict drivers that we can directly observe, identify, and quantify? Proponents argue that, while there is a need for further exploration, our evolving understanding of unconscious bias and its influence offers practitioners and researchers valuable data that can contribute to positive change. Knowledge of unconscious bias can raise awareness among mediators and conflicting parties regarding their own implicit biases, and it may enable practitioners to better address the intricate, unseen, and often unspoken, dynamics at play in intergroup conflicts.

It is also important that interventions targeting unconscious bias are viewed as part of a comprehensive strategy. This strategy should address both individual biases and systemic societal factors, such as discriminatory attitudes and popular and political discourses that foster division. By combining unconscious bias interventions with complementary approaches, we can work towards conflict resolution processes that lead to more sustainable, equitable, and effective outcomes.

On a final note, in her book ‘Our Brains at War’,Mari Fitzduffreminds us that, while our ancestors’ tendencies to form groups that compete with one another can prevail in our intergroup relationships, we, as ever-evolving human beings, have proven our ability to move beyond our own tribes to interact with others in an increasingly interconnected world. In his work on ‘moral imagination’, John Paul Lederach also emphasises that peacebuilding is an artistic endeavor that demands creativity, continuous innovation, and a deep understanding of the essence of conflict. Though unconscious biases tend to be perceived negatively, it is important to recognise them as features, not flaws, of our human brains in order to understand, and mitigate, their impact on conflict dynamics.[xviii]

Emma Ciccarella is a freelance conflict researcher and junior consultant at TrustWorks Global. She has experience in conflict analysis, mediation, and psychology, through her work on West Africa and the Middle East in organizations such as the International Crisis Group and Promediation. She holds an MSc from the Psychological and Behavioural Sciences department of the London School of Economics.

This blog was originally published by the International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation: read it here.

[i] Dan Jones. (2016). Untying the hardest knots. Accessed at: https://www.bps.org.uk/psychologist/untying-hardest-knots

[ii] Mari Fitzduff. (2021). Our Brains at War – The Neuroscience of Conflict and Peacebuilding. Oxford University Press; John Paul Lederach. (2010). The Moral Imagination: The Art and Soul of Building Peace. Oxford University Press; H.C. Kelman (2007). Social-psychological dimensions of international conflict. In Zartman, I. W. Peacemaking in international conflict: methods & techniques. United States Institute of Peace Press; Daniel Kahneman. (2012), Thinking, Fast and Slow. Penguin.

[iii] https://implicit.harvard.edu/implicit/education.html

[iv] Jesse Singal. (2017). Psychology’s Favorite Tool for Measuring Racism Isn’t Up to the Job. The Cut

[v] Mari Fitzduff. (2021). Our Brains at War – The Neuroscience of Conflict and Peacebuilding. Oxford University Press.

[vi] Jonathan Shay. (1995). Achilles in Vietnam: Combat Trauma and the Undoing of Character. Scribner.

[vii] Henri Tajfel. (1978). Differentiation between social groups: Studies in the social psychology of intergroup relations. Academic Press.

[viii] Mari Fitzduff. (2021). Our Brains at War – The Neuroscience of Conflict and Peacebuilding. Oxford University Press.

[ix] Helen Winter & David Hoffman. (2022). Follow the Science: Proven Strategies for Reducing Unconscious Bias. Harvard Negotiation Law Review, 28(1).

[x] D. O’Brien & Kathleen Wayland. (2015). Implicit Bias and Capital Decision-Making: Using Narrative to Counter Prejudicial Psychiatric Labels. 43 HOFSTRA L. Rev. 751, 772–80.

[xi] https://r3solute.com/r3solute-programmes/

[xii] Interpeace. (2023). Mind the Peace: Integrating MHPSS, Peacebuilding and Livelihood Programming: A guidance framework for practitioners, February.

[xiii] C. Chavez & J.Y. Weisinger. (2008). Beyond diversity training: a social infusion for cultural inclusion. Human Resource Management. Vol. 47 No. 2, pp. 331–350.

[xiv] Shelley McKeown & John Dixon. (2017). The “Contact Hypothesis”: Critical Re- flections and Future Directions, Soc. & Personality Psych. Compass. Vol. 11.

[xv] Barlow, F. K., Paolini, S., Pedersen, A., Hornsey, M. J., Radke, H. R. M., Harwood, J., … Sibley, C. G. (2012). The contact caveat: Negative contact predicts increased prejudice more than positive contact predicts reduced prejudice. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin.

[xvi] Paolini, S., Harwood, J., & Rubin, M. (2010). Negative intergroup contact makes group memberships salient: Explaining why intergroup conflict endures. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin.

[xvii] Helen Winter & David Hoffman. (2022). Follow the Science: Proven Strategies for Reducing Unconscious Bias. Harvard Negotiation Law Review, 28(1).

[xviii] Dan Sperber & Hugo Mercier. (2017). The Enigma of Reason. Harvard University Press. Daniel Kahneman. (2011). Thinking, Fast and Slow. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Six and a half years ago, the self-proclaimed Islamic State (IS), also known as Daesh, was driven out of Mosul. Under the terrorist group’s control, the city and its identity was attacked. In pursuit of their extreme version of Salafism and the creation of a caliphate, IS killed friends, families, neighbours, and broke up communities. The group committed urbicide, destroying important cultural heritage sites in an attempt to extinguish the cosmopolitan spirit of the city. Thousands were forced to flee their homes during the three years of this violent regime.

IS aimed to erase the Mosul that so many knew, loved, and identified with, but if you were to visit the city now, you would see that it’s beginning to recover. Spearheaded by both local and international initiatives, rebuilding efforts are underway. And, while they work hard on clearing the rubble and restoring the built environment, Mosul’s citizens are dealing with the psychological and emotional scars of the conflict. Because post-conflict reconstruction is not just a case of laying bricks. It’s about laying the ground for reconciliation.

Al-Nabi Jarjis Shrine and Mosque. Credit: Craig Larkin

Old souks in Mosul. Credit: Craig Larkin

I travelled to Iraq in May 2023 with my colleagues on the XCEPT research programme, Dr Craig Larkin and Dr Rajan Basra, to see how communities in and around Mosul, and the wider province of Nineveh are trying to move forward after the conflict.

The purpose of our trip was to learn more about the work being done as part of the reconstruction process, and to better understand the hurdles that stand in the way of post-conflict recovery.

Dr Inna Rudolf, photographer Ali al-Baroodi, and Dr Craig Larkin by a statue celebrating the role of locals in rebuilding Mosul after its liberation. Credit: Inna Rudolf

Our research began in Baghdad, where we met with officials from the Iraqi Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Ministry of Culture. We had noted a considerable increase in the Iraqi government’s dedication to expediting the reconstruction and stabilisation process in Nineveh, and we were keen to understand the ministers’ perspectives on the role of culture in facilitating recovery.

Dr Inna Rudolf and Dr Craig Larkin at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Credit: Inna Rudolf

Although there was widespread acknowledgment among government officials of the importance of culture, we discovered that there was still a lack of coordination in developing an approach that integrated culture and heritage promotion with measures that tangibly improved people’s living conditions.

We left Baghdad with assurances from decision-makers that they would continue to accelerate reconstruction efforts. Keen to assess if local communities were genuinely regaining trust in the government’s commitment to improve their livelihoods, we made our way to the city of Erbil.

From Erbil, we embarked on trips to the cities and towns of Mosul, Bartella, Sinjar, Lalish, and Sheikhan. Despite being well-acquainted with the latest updates on Mosul’s reconstruction process, witnessing the city in person still profoundly affected me. Under IS, 47 architectural sites had been deliberately demolished, and following the group’s rule and the battle for Mosul’s liberation in 2017, 80 percent of the Old City had been destroyed.[i] The sheer extent of destruction and the countless damaged buildings reduced to rubble were stark reminders of the immense challenges still facing the city’s residents.

A destroyed building in Mosul. Credit: Rajan Basra

While in Mosul, we had the pleasure of being taken on a guided tour of the city’s cultural landmarks by my friend and famous Moslawi photographer, Ali Baroodi. He not only showed us the emblematic Al-Nouri Mosque, but he also took us around Al-Tahira Church, Al-Saat Church, and revealed some hidden jewels of the enchanting old Bazaar.

While enjoying a cup of traditional Moslawi coffee at one of the city’s ancient breweries, Ali told us about the historic importance of the old storage houses, where Moslawis used to store wheat and provisions for darker days. Having experienced notables or pashas – a form of notable – taking away the crops they had harvested, the city’s residents had learned the hard way to always have something hidden away for bad times. Ironically, as Ali playfully remarked, these anecdotes, when divorced from their historical context, have contributed to the misleading stereotype of Moslawis as being frugal. Delving into the true background of their unique self-preservation instincts, and unwavering determination to assert their rights and survival throughout history, was truly captivating.

The interior of Al-Tahira church. Credit: Rajan Basra

The old Bazaar. Credit: Inna Rudolf.

Al-Nouri Mosque. Credit: Inna Rudolf

We also visited the University of Mosul’s Central Library. In the collective consciousness of Moslawis, the library remains one of the most important cultural institutions in Iraq, with a collection of over one million books and historic manuscripts. Despite the extensive damage inflicted by IS, UNESCO, working in partnership with the Iraqi Ministry of Culture and local communities, was able to restore the library to its former glory, which included salvaging many damaged books and manuscripts. Although the design of the reconstructed building focused on preserving its architectural heritage, modern features and technologies were also included to meet community needs.

Some signs of damage on the walls of Mosul’s library have been purposefully left intact. As the Iraqi historian Omar Mohammed argued, these scars were left both to remind people of what had happened, and to help them move on with their lives: ‘We need to use this tool to help the people heal the trauma they have been living, to help them ease the shock they have gone through and the very troubling experience of Daesh.’

Alongside the reconstruction of the built environment, my colleagues and I were interested in tracing the recovery of the city’s unique spirit. We’d chosen to focus our peacebuilding and recovery research on Nineveh because of its vibrant social fabric, and because of the symbolic significance Mosul has historically embodied as a beacon of cosmopolitanism.

I’ve frequently travelled to different parts of Iraq over the last seven years to carry out fieldwork, but this was the first time I was able to interview local practitioners and community leaders on the ground, who are working hard at the grassroots level to help the city move forward.

We had the privilege of meeting the remarkable team at Volunteer With Us, an organisation that epitomises the power of collective action in rebuilding the city and transforming the lives of its residents. In the aftermath of the conflict, their campaigns rallied people together, united in their mission to clear neighbourhoods of debris and wreckage. Over time, the organisation has shifted its focus to work closely with schools, raising awareness about vital environmental policies, nature preservation, and the promotion of culture.

Ahmed Mohammed, founder of Volunteer with Us, Dr Rajan Basra, Dr Craig Larkin, Ayoub Thanoon from Mosul Heritage House, and Dr Inna Rudolf at the Volunteer with Us headquarters. Credit: Inna Rudolf

Their headquarters, nestled within the grounds of a lovingly reconstructed historic house proudly bear a banner that reads ‘Volunteer with Us!’ The building serves as a testament to their commitment to preserving the past while invigorating the present, creating a space that beckons locals and visitors alike.

Volunteer with Us. Credit: Inna Rudolf

This harmonious fusion amplifies the power of heritage, fostering a sense of collective engagement and inviting diverse individuals to contribute their time and skills. In an interview with us, the founder, Omar Mohammed, connected his vision for the initiative to the Moslawis’ responsibility to live up to the heroism of their legendary ancestors:

Our history can be traced back to numerous civilisations, kings and empires such as the Ancient Assyrian Empire, Sumerian civilisation, and Hammurabi who was the king of the old Babylonian Empire. Our achievements paused during the recent years. Today, Iraqis want to realise numerous achievements and victories. We, as youth, want to leave a positive mark on our contemporary history. Through our work we hope to send a message of peace and strength. It is crucial for Iraqis to recognise their impressive past and history, which will motivate them to continue this legacy and strive to help our country.’

Witnessing the volunteers’ unwavering dedication underscored the invaluable role of grassroots efforts in fostering positive change and renewal within the city. It’s important to make sure that such initiatives have access to funding resources comparable to those available to larger and more prominent organisations. Championing these lesser known, but impactful, ventures will help foster a diverse and inclusive landscape of support, propelling positive change and transformation throughout society.

Volunteer with Us logo. Credit: Rajan Basra.

At Mosul Heritage House, my colleagues and I were shown around by Ayoub Thanoon, the founder of the Mosul Heritage project. This old house, which was partially destroyed during the conflict with IS, was restored with particular attention given to preserving aspects of the house’s traditional Moslawi architecture. The house is now rented by the Mosul Heritage project, who have turned it into a museum, and who use it as a base for cultural events, forums, and seminars, which draw visitors from across Iraq.

During our visit, Ayoub showed us around the different sections of the house. The first section includes several rooms with interiors replicating conventional Moslawi living spaces such as a traditional saloon, in which the household members would gather for coffee or receive guests.

Mosul Heritage House. Credit: Inna Rudolf

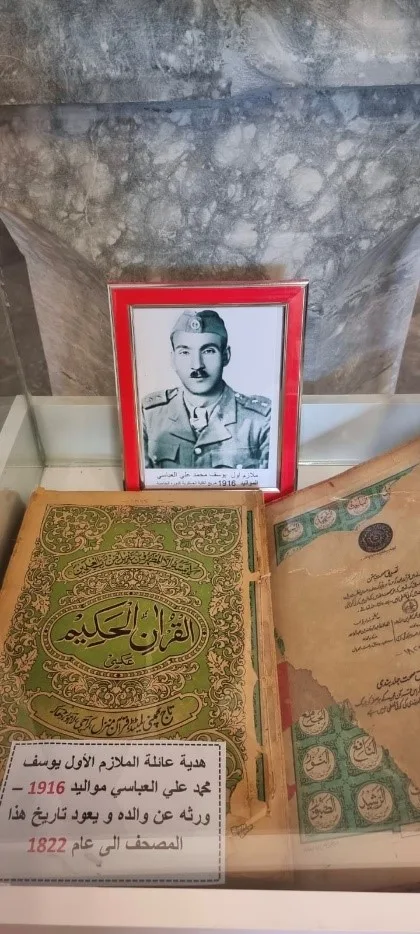

The second section is dedicated to the community centre which aims to inform visitors about UNESCO’s ‘Revive the Spirit of Mosul’ project.’ The third section hosts an impressive heritage museum with lovingly collected artefacts from different epochs of the city’s history, such as old sewing machines, record players, and newspapers and banknotes dating back to Iraq’s short-lived monarchy period.

Mosul Heritage House. Credit: Inna Rudolf

Ayoub hopes that, as well as rescuing and preserving Mosul’s identity, the museum will educate Moslawi youth about the history of their city. The organisation has now expanded its activities across the Nineveh governate, organising study trips and excursions which connect different communities and contribute to the development of a shared pride in the governorate’s heritage.

Ayoub Thanoon and Inna Rudolf at Mosul Heritage House. Credit: Inna Rudolf

The holistic approach adopted by Mosul Heritage Organisation serves as a model of people-centred heritage promotion and preservation initiative that has a real capacity to improve locals’ livelihood prospects, through its success in attracting tourists, while contributing to the emotional recovery and social reconciliation of conflict-affected communities across the province.

A similarly impactful, community-driven initiative was launched in 2019 by the talented journalist and cultural entrepreneur Saker al-Zakariya. Founding the Baytna (Our Home) Institution for Culture, Heritage and Arts, Saker sought to showcase the healing power of Mosul’s rich cosmopolitan legacy. Designed by Saker as a ‘place that deals with the Moslawi identity’, Baytna’s headquarters can be found in a 100-year-old traditional house, painstakingly restored with meticulous care and dedication, in the heart of Mosul’s Old City.

Intended to help rekindle the pride of Mosul’s residents in the unique heritage of their city, the walls of the museum house are decorated with portraits of famous local artists, writers, public figures, and even internationally renowned celebrities, such as star architect Zaha Hadid, who have left a mark in the collective consciousness of Iraqis.

Portraits of public figures adorn the wall of Baytna. Credit: Inna Rudolf

Displaying the generous donations from some of the city’s residents, an artfully curated collection of vintage items is delicately arranged on shelves crafted from aged driftwood, offering visitors a glimpse into the daily life of a bygone era, stretching back a century prior to the recent conflicts. Visitors are also invited to immerse themselves in Mosul’s Ottoman and monarchical past by adorning themselves in traditional costumes and wool fez hats.

Completing the time travel experience, on the rooftop, dressed in traditional attire, members of the Baytna team serve visitors authentic beverages and refreshments, while sharing entertaining stories about various stages of the heritage house project. It comes as no surprise that Baytna is a preferred spot for an array of cultural events such as public readings, concerts, and art exhibitions.

While Baytna can be read as a heartfelt declaration of the founder’s love for his city, this passion stems from his personal journey of coming to terms with Mosul’s violent history:

‘Since 2005, the city of Mosul meant nothing to me. I hated, loathed, detested it. I lost so many friends in the city. I tried to stay away from it. The night of its downfall in 2014, I cried hysterically until the morning because I felt for the first time I belong to the city, but at the same time I had lost the city. When Mosul fell, I started to feel a sense of belonging to Mosul. I began to identify myself as a Moslawi.’

Realising what was at stake upon witnessing the destruction of the city’s cultural heritage, Saker embarked on the mission of restoring his own nostalgic version of Mosul as the city which he remembers from the time before 2005, when armed Islamist groups such as al-Qaeda had started to undo the unique diversity of its social fabric:

’This foundation is mainly engaged in preserving and maintaining our heritage, our identity in Mosul … This foundation became an emblem to revive the city of Mosul. The French President demanded to visit us at the foundation during his trip to Mosul. More than 400 tourists came to visit us last year, ambassadors, the Iraqi prime minister – they all came to visit us.’

Saker takes immense pride in resurrecting fragments of the city’s glorious legacy and helping dispel the stigma haunting its residents. Oftentimes, their victimhood and identity are misunderstood by their fellow citizens.

For instance, Mosul has been known as the ‘city of a million officers’ due to the significant representation of Moslawis in the army during Saddam Hussein’s regime.[i] Unfortunately, this has led to unfair prejudices, with Moslawis being unjustly labelled as supporters of the Baath party – the party which brought Hussein to power and allowed him to rule as a dictator in Iraq for over three decades. Such sweeping generalisations fail to recognize the historical context: the military career ingrained in the identity of Moslawi communities dates back to Ottoman times when the city hosted essential military barracks, and this history of military service has continued throughout the centuries, regardless of which regime held power.

Saker’s efforts not only preserve the city’s history but also challenge misconceptions, allowing for a more nuanced understanding of Mosul’s past and its people. By shedding light on the rich heritage and traditions of Moslawis, Saker aims to bridge the gap of misunderstanding, fostering greater unity and appreciation among different communities.

Baytna. Credit: Inna Rudolf

In a sense, both Ayoub’s and Saker’s personal fascination with the city’s cultural heritage, and their commitment to restoring Mosul to its former glory, represents their longing for a more distant past, uncontaminated by sectarian identities. This is not escapism, but rather a desire to give hope to Mosul’s traumatised youth, to help them restore their pride in the city, and to help them move beyond the divides that IS tried to sow. Because there are still rifts that need healing. It may have been six years since Mosul was controlled by IS, but there are still an estimated 100,000 Moslawis who have chosen not to return home, or who have been unable to.

During our time in Iraq, we also looked more broadly at the role of different ethnic and religious minorities. In Sinjar, we visited the House of Co-existence in Sununi, headed by the famous human rights activist Mirza Dinnayi.

House of Co-existence. Credit: Inna Rudolf

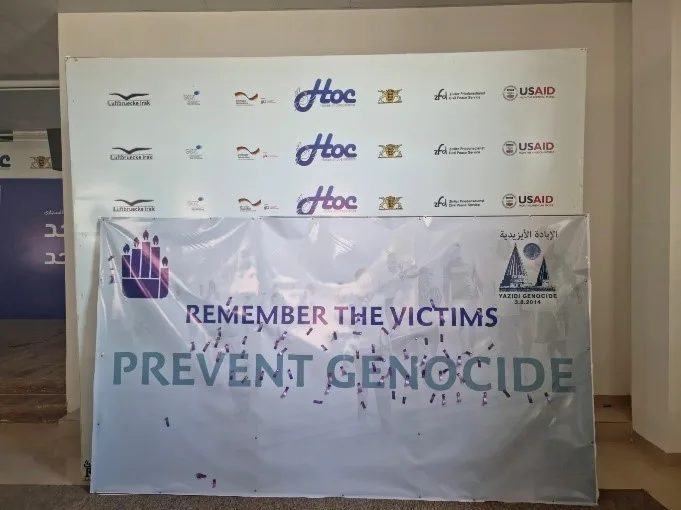

We also had the opportunity to visit the Yazidi temple in Lalish and partake in a cultural festival in Sheikhan. The Yazidi people are an ethno-religious minority group who were largely based in the Sinjar region in northern Iraq, and who suffered severe atrocities at the hands of IS. On 3 August 2014, IS invaded the Yazidi heartland and, in the space of two weeks, killed over 5,000 men, enslaved thousands of women and children, and caused the displacement of hundreds of thousands. Today, thousands of Yazidis are still missing, and an estimated 200,000 remain displaced.[i] Engaging with the elders during these encounters, we gained insight into the numerous challenges they confront due to their religious beliefs, hindering them from fully experiencing a sense of equal citizenship in Iraq. For example, we learned about instances where representatives of other religious communities would decline Yazidi-prepared food, as they deemed it ‘impure’. These experiences emphasised the importance of addressing religious tolerance and promoting inclusive coexistence to foster a harmonious society.

The town of Sheikhan. Credit: Imad Qusay Abbas

We gathered valuable insights into the tensions prevalent in Nineveh, particularly concerning the Turkmen from Tal Afar, specifically Sunni Turkmen, who bear the burden of being stigmatised for their perceived support of IS. Historical accusations against Turkmen from the outskirts of Mosul, particularly those from Tal Afar, have also labelled them as overly eager to climb the social ladder and align themselves with unjust causes and regimes to enhance their social mobility.

These perceptions can be traced back to the purported / reported conduct of some Sunni Turkmen during the Baath party regime under Saddam Hussein. Consequently, some local Sunni Arabs in Mosul tend to hold Turkmen responsible for the stigma associated with Moslawis as supposed IS supporters or Baathists.

Dr Inna Rudolf at the Yazidi temple in Lalish. Credit: Imad Qusay Abbas.

In Nineveh, due to the involvement of certain Sunni Arabs with IS, there are individuals who tend to generalise Sunni Arab Moslawis as a community that condoned or tolerated the extremist group. The Sunni Arab Moslawis, however, strongly reject this assertion. The complexity of these dynamics emphasises the need to address historical grievances and correct misperceptions in order to foster mutual understanding and reconciliation within the diverse communities of Nineveh. Hence, the renowned initiative Mosul Eye, founded by the prominent historian Omar Mohammed, has undertaken a noteworthy endeavour, collecting oral histories and testimonies from different communities throughout the Nineveh region. These accounts serve to both preserve collective memories of the past and illuminate aspirations for the future.

The initiatives we saw in Mosul go far beyond the obvious contribution to restoring the city’s built heritage. They have an undeniable impact on locals’ emotional and psychological healing. These initiatives should not be evaluated primarily against the background of the ‘authenticity’ of the rebuilt structure, but should instead be measured by their ability to influence local communities’ feelings of pride and belonging to their built and social environment.

Ali al-Baroodi, Dr Inna Rudolf, and Dr Craig Larkin in Mosul. Credit: Rajan Basra.

For Mosul, for Nineveh, and for Iraq to move forward, trust in the state needs to be restored. To achieve effective post-conflict stabilisation, it is crucial for the Iraqi government to be perceived as the driving force behind both economic and cultural recovery. This entails the international community occasionally taking a back seat and refraining from seeking credit and visibility for its substantial contributions. By empowering and urging the Iraqi government to provide adequate support to the burgeoning civil society scene, the international community can better facilitate the nation’s journey towards sustainable progress and self-determination.

The international community can also do better in supporting the efforts of local actors, those working hard on the ground to rebuild their own communities.

Reconstruction in the Old City of Mosul. Credit: Rajan Basra.

Furthermore, the Iraqi state faces the critical task of addressing the fate of internally displaced people. For those who wish to return to their homes, the government must establish sustainable measures to ensure their safe and supported reintegration. At the same time, as some individuals are in the process of establishing new lives in different locations, it is vital for both the Iraqi government and international organisations to actively cultivate a sense of belonging to the state. Measures should be taken to facilitate meaningful connections between these ’newcomers’ and other communities affected by the conflict. Collaborative efforts in these domains are crucial to lay the foundation for a more cohesive and harmonious society.

One thing my colleagues and I left Mosul with was a great sense of responsibility towards all the people that opened their homes and their hearts to us, and who shared with us their dreams, fears, and their experiences.

It is important to make sure that their stories, and their perceptions of conflict and post-conflict realities, are heard and reported accurately so that decision makers and donor organisations can understand the challenges different communities face and what they can do to better support them.

Mosul may bear a history of conflict, but it also boasts a legacy of coexistence and a remarkable resilience, akin to the mythical phoenix rising from the ashes. It is precisely this enduring spirit that local champions are striving to revive and reclaim.

Statue celebrating the role of locals in rebuilding Mosul after its liberation. Credit: Inna Rudolf

This XCEPT blog was originally published by King’s College London on the International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation website.

You can read more about the findings from this XCEPT research in the recently-published journal article, Iraqi heritage restoration, grassroots interventions and post-conflict recovery: reflections from Mosul.

[i] https://www.newarab.com/news/iraq-announces-return-487-yazidis-sinjar

[i] Interviews with Iraqi practitioners, 2022

[i] Monuments of Mosul in Danger project. Accessed at: http://www.monumentsofmosul.com/index_htm_files/Monuments%20of%20Mosul%20in%20Danger.pdf

In this episode, Dr Craig Larkin and Bronte Phillips discuss how the still-escalating conflict between Israel and Hezbollah affects people in Lebanon. They consider how increasing violence has reignited memories of previous conflict trauma with Israel, how prior Lebanese experiences impact present attitudes in the here and now, and explore why the ongoing conflict risks embedding tensions between the diverse populations living in Lebanon.

In this episode, Mohamad El Kari, translator with King’s College London on the XCEPT project, speaks about the personal and professional challenges he faces in the course of his work. He explores the importance of understanding local culture, the need to remain sensitive to different interpretations of a word or phrase, and the ethical and moral difficulties that arise when working in the context of a conflict. Mohamad also turns to the issue of wellbeing, highlighting the emotional toll that a translator can face when working with stories of conflict trauma.

Currently much of the world’s attention is focused on the UN’s struggle to achieve a ceasefire and avert humanitarian catastrophe in Palestine. At the same time, another devastating war rages in Sudan, with similarly violent consequences for millions of people and an inability to reach a ceasefire.

Sudan is now the country with the largest number of displaced people in the world – more than 11 million people. Since April alone, 5.4 million people have been internally displaced and 1.3 million have fled to neighbouring countries including Chad, Egypt, and South Sudan. While over half the population – 25 million people (including 13 million children) – urgently need humanitarian assistance.

The toll of the war on civilians continues to worsen, with devastating intercommunal violence and ethnic cleansing across Darfur, huge infrastructural damage, as well as loss of livelihoods and escalating humanitarian strife.

On the surface, the war in Sudan may seem like a typical civil war. Two rivals, the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), are fighting for land and power.

The RSF have made gains in Khartoum and Darfur, where they are consolidating control, while the SAF have suffered a series of humbling defeats that seem to have made elements within their leadership more open to negotiations.

An effective partition has emerged in Sudan, with the SAF controlling the east and northeast and RSF controlling much of the capital and west of the country.

Looking at the conflict in Sudan as merely a civil war between two national groups is misleading. Sudan sits at the confluence of four regions, the Horn of Africa, North Africa, the Sahel, and the Arabian Gulf across the Red Sea.

Both the SAF and RSF engage economically, politically, and militarily with a motley of governments and armed groups from these regions (and beyond) to fight their war.

In its pursuit to control the supply chain of gold, the RSF has extended its economic operations beyond Sudan’s borders, selling primarily to the United Arab Emirates (UAE), which has consequently become a key backer.

The SAF accrue rents not only through taxing exports and imports transiting Port Sudan, but also by receiving support from foreign governments including Egypt, Qatar and Turkey, including via the sale of strategic commodities such as gold and livestock. Economic processes not only connect Sudan to the region, but also facilitate the supply chains that fuel and sustain the conflict.

Sudan sits at the confluence of four regions. Both the SAF and RSF engage with a motley of governments and armed groups from these regions to fight their war.

These foreign actors also view Sudan as a playground for their own pursuit of regional influence. For instance, the UAE competes against its Gulf rival Qatar, with the former backing the RSF and the latter supportive of the SAF.

The UAE leverages its other regional allies, from Libya’s Haftar to the government of Chad, while the SAF have sought support from Turkey and Iran in providing them with drones to use in the war. These positions have complicated attempts to mediate between the warring parties during the Saudi–US sponsored Jeddah talks.

Many fear that without a swift and durable ceasefire this war could divide the country, with both sides declaring their own governments. If the war becomes protracted then further fragmentation and militarization is likely, including along ethnic lines. This will only worsen the humanitarian disaster and regional spillover.

A sense of growing urgency has driven recent mediation efforts by the regional bloc IGAD, given the limited success of other interventions to date. However, the lack of heft and collective approach needed of the international response has contributed to the inadequacy in resolving the war. This means negotiating not only between the two sides, but navigating all the transnational actors who have a stake in the conflict.

Many conflicts around the world suffer from similar dynamics, but policymakers often engage them as bounded by national borders, excluding the interests and influence of actors who fuel the conflict from other countries.

This is partly a product of the structures of foreign policy and international development. For instance, the UK government has for several years administered Joint Analysis of Conflict and Stability (JACS), used to guide the National Security Council Strategies. These JACS are in most cases country-focused, meaning they are based on the analysis of conflict advisors and external consultants who work on the country in question.

What the exercise often misses, however, is analysis from advisors and experts who work on countries that seem geographically distant, but which nonetheless have a stake and fuel the conflict. In such cases, regional JACS should be more central to decision-making. In Sudan, for example, the wide array of country teams which focus on the Horn of Africa, the Sahel, Egypt, the Gulf, Turkey, and Iran, should all be part of the analysis of the current conflict.

The gap in the analysis phase extends to both policymaking and programming in these conflicts. Most programmes that deliver aid or offer institutional support (like building hospitals or implementing anti-corruption initiatives) are confined to teams which focus on the country where the conflict has erupted.

However, these initiatives again become susceptible to transnational actors and processes which are not always identified by the country-specific focus. This means that potential spoilers may be present which do not map on the policymakers’ horizon, challenging the sustainability of peace agreements or development projects.

In the Middle East and Africa, armed conflicts that have erupted in places like Sudan are not confined to national borders. These dynamics are also seen in the conflict in Sinjar, Iraq, where armed groups with authority across multiple countries vie for control; or in Libya where the smuggling and trafficking of people from Nigeria across multiple borders fuels conflict along the way; or in Israel and Palestine where regional and foreign governments arm and support one side or the other.

None of these conflicts are isolated from their wider regional and international arenas of interlocking actors, processes, and geographies that transcend the bounded terrain of nation states. Yet, current initiatives by foreign governments or multilateral organizations approach them by doubling down on those national borders.

This includes either closing off or securitizing borders, or focusing conflict response mainly on actors who come from within those borders. While external interests are often understood, solutions are developed largely in national terms, often sidelining the more complicated web of foreign influence.

Chatham House’s XCEPT research works to bridge these gaps and consider how transnational dimensions of conflict fuel and (re)produce armed conflict, often over great distances. This reality is critical to understanding why and how armed violence erupts and, critically, how to achieve more sustainable peace.

Although the roadblocks spanning Somalia are initially easy to disregard as bureaucracy, in practice they are pressure points that connect multiple actors shaping trade networks and political projects across the Somali territories. While researchers already know that terrorist groups like Al-Shabaab value road-blocks, this podcast discussion focuses on lesser-known checkpoints operated by various actors and the impact these roadblocks have upon their surrounding region.

The podcast guests, who have each recently released an XCEPT-funded paper exploring how terrorism, political interests and economic regulation collides in Somalia, come together to untangle the fluid web of roadblocks and checkpoints evolving in Somalia’s ever-changing political landscape.

This podcast has been produced by the Rift Valley Institute (RVI) as part of the FCDO’s Cross-Border Conflict Evidence, Policy, and Trends (XCEPT) Program, a consortium initiative funded by UK Development. XCEPT brings together leading experts to examine how conflicts connect across borders and the factors that influence both violent and peaceful behavior in conflict-affected borderlands.

The UK Aid-funded Cross-border Conflict Evidence, Policy and Trends (XCEPT) research programme seeks to better understand conflict-affected borderlands, how conflicts connect across borders, and the factors that shape violent and peaceful behaviour, to inform effective policy and programme responses. Led in part by Chemonics UK, XCEPT hones in on the behavioural dimensions of conflict in partnership with King’s College London (KCL), who explore how memories, motives, and trauma and mental health affect pathways to violent/peaceful decision-making over time.

The Chemonics XCEPT team and our local research partners undertook a mixed methods field study in northeast Syria in late 2021. As part of this work, we sought to better understand the impacts of conflict and violent extremism on adolescents in the region. We also considered potential drivers of vulnerability to violent extremist sympathy, as well as factors that may support adolescent resilience. Our field research findings echo wider academic research on violent extremism. There is no single, linear pathway toward radicalisation. Instead, a variety of contextual factors, individual incentives, and other enablers emerged as relevant to consider, but which should not be seen as determinative.

XCEPT programme research underway through KCL further examines potential linkages between adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and vulnerability to violent extremism, among other potential negative outcomes. In our field research, negative outcomes we observed include depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or other manifestations of trauma, and vulnerability to violence, criminality, and drug abuse. Other research with Syrian children and adolescents has demonstrated very high rates of mental health problems, with over half of 8-16-year-old Syrians living as refugees in Lebanon meeting the criteria for PTSD, depression, anxiety, or externalising behaviour problems. Many children met criteria for more than one disorder, better characterised as complex trauma reactions driven by chronic adversity as well as past exposure to conflict. These findings highlight the importance of addressing adolescents first and foremost as victims of conflict and avoiding stigmatisation as potential violent extremists.

Adolescents in northeast Syria are growing up in a context where social cohesion has frayed, with the conflict upending traditional sources of individual and community resilience. The normalisation of violence has shaped adolescents’ behaviour. Displacement is a near-universal experience that prompts feelings of loss, hardship, and isolation. Ineffective local authorities oversee an uneven recovery, with a worsening economic crisis and disrupted education constraining adolescents’ hopes for the future. A sense of uncertainty and despair permeates the adolescent experience, alongside a widespread desire for a return to ‘normalcy.’

Our research found that access challenges, quality constraints, and safety risks all undermine education services in northeast Syria. Older adolescents in particular are increasingly dropping out of school as their families struggle to make ends meet. For boys, this often means looking for work, while for girls this frequently results in early marriage. Local authorities are unable to grant accredited certifications, and the costs of private tuition and travel to regime-held areas for official examinations are prohibitive for many families. Insecurity on the journey to/from and within schools further reduces attendance and affects adolescents’ mental health.

Based on the findings of XCEPT’s research, Chemonics and partners designed an informal educational curriculum and delivered a ten-week pilot programme for adolescents and youth aged 12-18 in northeast Syria (Deir Ez-Zor and Raqqa). The pilot programme incorporated constructs identified as relevant by the research, including social and emotional learning (SEL), instilling a sense of agency, and critical thinking skills. The pilot curriculum emphasised a life skills-based, informal educational approach, incorporating methods such as arts and self-reflection activities that resonated with adolescents in the fieldwork. At the end of the pilot, the programme observed statistically significant increases among adolescent participants across all domains.

Taken together, the learnings from the successful pilot programme and the findings from our study yield important considerations for the design and delivery of interventions that aim to strengthen adolescent resilience:

Visit UKFIET, where this article was originally published.