Trauma interventions in fragile areas can help to break cycles of conflict, because we know that exposure to violence causes trauma, but that trauma can also cause violence. But these interventions are often delivered for only a narrow group of people deemed to be ‘worthy’ of them. In reality, the distinction between victim and perpetrator in conflict-affected populations isn’t quite so clear cut.

In this episode of the ‘Breaking Cycles of Conflict’ mini-series, Dr Gina Vale interviews Dr Alison Brettle about her research into trauma interventions. Dr Brettle explains what programmes work best in fragile and conflict-affected areas and why the international donor and policy communities need to broaden their conceptualisation of who should be allowed to participate in interventions.

The Libyan city of Kufra is an important trade hub for goods crossing its borders with Sudan and Chad. Since 2011, human smuggling has come to play a complex role in Kufra’s economic development and overall stability, providing counter-intuitive findings for international policymakers.

Communal disputes

Kufra’s population comprises two main groups: Arabs and Tebus. The Arab community in Kufra numbers around 55,000 people – of which approximately 42,000 are from the Zway community, and 5,000 from non-Zway tribes – while the indigenous Tebu community consists of around 8,000 people.

Longstanding rifts exist both between and within these communities. While Kufra’s communities were united in their support of the overthrow of the Gaddafi regime in 2011, they have not agreed on what should come next. The Tebu have sought greater representation in local government while the Zway have sought to maintain sole control of the local governance system.

The divisions within the city are literal as well as figurative. Residential areas are split between Tebu and Zway, and Zway residential areas are also divided by familial branches. While the Gaddafi regime had developed several mixed residential areas and sought integration of the communities in the city’s schools, divisions hardened following the revolution.

In 2014, in response to the Tebu community’s request for greater political representation, Libya’s eastern-based interim government approved the establishment of a separate Tebu local governance authority in Kufra and Rebiana oasis. The Zway community’s response to this perceived threat contributed to a significant outbreak of violence in which over 100 people are believed to have been killed and hundreds more were displaced.

The Zway’s military victory gave them control over the local security sector. The city’s security directorate, akin to police, and the dominant armed faction, Subul al-Salam – affiliated to the Libyan Arab Armed Forces (LAAF) of Khalifa Haftar – became armed factions of the Zway community, excluding Kufra’s Tebu minority. The Tebu also failed to achieve their political objectives as their parallel local council was transformed into a committee under the authority of the Zway-run Kufra municipal council in 2017.

The development of cross-border trade

From the 1960s to the 1980s, over 50 major agricultural projects were completed in Kufra, firmly establishing agriculture as a critical element of the local economy. However, the impact of war with nearby Chad (1978-87) saw Kufra become a militarized area. In addition, international sanctions applied following the Lockerbie disaster meant Kufra’s agricultural projects could not secure the necessary replacement parts and many fell into disrepair.

People instead turned to cross-border smuggling as a quick source of income. Historically, Kufra had been a vital waypoint for trade caravans from African Wadai and Kanem-Bornu kingdoms to Egypt. Electronics smuggling and cattle imports during the Gaddafi era meant Kufra residents enjoyed relative economic well-being. These semi-licit activities were encouraged by the customs authority, whose employees came from big cities such as Tripoli and Misrata to compete for work at the lucrative Oweynat desert border crossing.

Human smuggling and trafficking: from conflict to cooperation

From 2012 to 2015, Kufra’s Zway and Tebu communities fiercely competed for control of border crossings and desert routes. In 2012, in an effort to gain exclusive control of the local cross-border economy, the Zway constructed large sand trenches around Kufra to curb Tebu-run cross-border trade, making it impossible to enter and exit Kufra without crossing through fixed checkpoints.

This effective siege of Tebu trade fuelled armed conflict between Tebu and Zway forces and inhibited the development of Kufra’s human trafficking and smuggling sector. However, following the consolidation of Zway control over Kufra in 2015, economic cooperation with the Tebu continued out of necessity.

While the Zway-dominated Subul al-Salam could monopolize the desert routes from Kufra to the Sudanese border, the route to northeast Libya remained difficult to use as a result of the security situation in the northwest. This meant that the Zway would cut deals with the Tebu to secure the movement of irregular migrants east through the Tebu-dominated Rebiana oasis and onward via the Fezzan region. By early 2017, the human smuggling and trafficking networks were operating freely via these routes.

Despite ongoing tensions, the mutually beneficial involvement in human smuggling and trafficking actually appears to have served as a source of stability among rival factions in Kufra.

Municipal funding underwritten by the smuggling sector

The income generated from the smuggling sector has led to reported improvements in the quality of life of Kufra’s residents. This is in part due to the 2017 establishment of the Kufra Construction Fund (KCF), set up by the Zway-controlled municipal council to provide a framework for Subul al-Salam’s expansive engagement in the economy. Negotiated by local Zway elites, the KCF is effectively a deal to split the revenues from the taxation of cross-border trade between Subul al-Salam and the local municipal council. In the face of limited and intermittent support from national government, this is an example of a very different form of decentralization to that envisaged by Western donors.

The KCF provides no effective legal cover in Libyan law. Municipal councils do not have powers to impose movement taxes and, in any case, the flows largely consist of illicit goods. Rather, this is a local solution to mitigate the lack of resources provided by central government.

Stability steeped in violence

The business of human smuggling and trafficking inflict serious harm on the migrants that cross the Kufra region; its detention centre is infamous and human rights abuses are widespread. But for the local population, the sector is also raising living standards and establishing a largely functional – albeit entirely illegal – system of municipal development.

Although the dispute between the Zway and Tebu communities over ancestral ownership of the region remains unresolved, business ties in the human smuggling sector appear to offer the clearest functioning linkages between them.

These developments show that stability – or simply the absence of fighting – does not necessarily mean the absence of conflict. In fact, the sort of stability seen in Kufra is steeped in violence, both structural with respect to the exclusion of the Tebu minority and direct with respect to the violence inflicted on non-Libyan migrants.

Stability of a less violent nature would require a set of economic alternatives to engagement in illicit trade and a social reconciliation that seem more distant now than at any point since 2011. The experience of Kufra also raises difficult questions for policymakers over what sorts of interventions to support in places that have come to thrive on cross-border illicit trade.

In the second instalment of this mini-series, we join Dr Craig Larkin and Dr Rajan Basra fresh off the plane from Beirut to talk about their fieldwork out in Lebanon interviewing ex-Islamist prisoners and their families. Interviewed by Dr Nafees Hamid, the pair discuss how historic conflicts, social inequalities, and personal traumas can all lead prisoners to pursue a path towards, or away from, extremism.

What drives one person to violence and another to peace? How does experience of trauma lead to radicalisation? Are there interventions that can help deflect people from trajectories of extremism? These are some of the questions that researchers in the XCEPT King’s College London team are trying to answer.

This research aims to understand the drivers of violent and peaceful behaviour, and to propose interventions and policies that can bring about peace. In the first episode of this mini-series, Dr Nafees Hamid and Dr Fiona McEwen introduce the work being done as part of the XCEPT programme at King’s College London and give us a glimpse of what’s to come.

Abdullahi Umar Eggi grew up in a nomadic family in Taraba State, Nigeria, and has undertaken extensive research to understand how and why pastoralism is changing in the region. He’s currently carrying out research on cross-border pastoralism, environmental change, peace and conflict along the borders of Nigeria, Cameroon and Niger as part of Conciliation Resources’ XCEPT research. Here, he tells us about his upbringing, and what he’s learning from his latest research.

I grew up in a Fulani nomadic family in Karim Lamido, part of Taraba State in northeastern Nigeria. I also spent time in Cameroon during my childhood, as my mother is Cameroonian. Growing up, I would migrate around north-eastern Nigeria and into Cameroon with my family in search of greener pasture for our livestock. This is called ‘transhumance’. It is a central part of our community life and identity; yet it also allowed me to gain a good understanding of the region’s topography as well as its many communities, including communities that weren’t from the Fulani tribe. The region is a patchwork of different tribes – there are around 200 in Taraba and Adamawa States alone.

I attended a nomadic school during my early years. Some of the nomadic schools were permanent structures while others were teaching under the shade of trees. The teachers were normally from the villages near our dry season and rainy season camps. For some weeks, during seasonal transhumance with our animals, there would be no school, but when we reached our destination, the children would proceed with their education in the nomadic school in the new location. These schools were well-resourced when I was young, but sadly pastoralist children nowadays struggle to get a decent primary education.

I met Adam Higazi, the lead researcher on the Promoting peaceful pastoralism project, during my time at University in Jos. We’ve been working togetherfor over 10 years now, exploring different facets of pastoralism across the whole region.

There is a general misperception in Nigeria of the relationship between pastoralism and issues such as criminality. We realised from our fieldwork that a lot of Nigerian media has a superficial understanding of what is happening on the ground; it’s widely reported that pastoralists from outside Nigeria – from Niger, Chad and Cameroon – are arriving in Nigeria and causing trouble. Our research to date hasn’t shown that to be the case. In Jigawa and Kano, some of the border communities we visited were not Fulani but actually Hausa and Kanuri – tribes seen to be less inclined to be friendly to pastoralists – but they reported to us that the cross-border herders were peaceful. In our study area in the central axis of northern Nigeria (Jigawa, Bauchi, Gombe), we found peaceful cooperation between pastoralists moving south from Niger during the dry season and their host communities.

At the same time, we can’t deny that there are pastoralists who are involved in violence and criminality in northern Nigeria. In Katsina, Zamfara and Sokoto States, towards Nigeria’s northwest, there are serious problems related to banditry. In these areas, many of those undertaking violence are Fulanis recruited into criminal gangs. But some of their biggest victims are Fulani pastoralists themselves; in these areas, pastoralists are routinely attacked and their livestock stolen. This creates the bandits of the future; when young pastoralist men lose their cattle they lose their livelihoods, and it makes them vulnerable to recruitment by criminal gangs.

This partly explains why banditry has rapidly escalated in Nigeria’s northwest, but it is not the whole story. Negligent governance has meant grazing reserves and cattle routes have not been maintained, and ‘land grabbing’ of common land has increasingly been allowed to happen. Despite the peaceful situation in our XCEPT study areas to date, we recorded these kinds of governance failings starting to play out, and worry that it will lead to increased cattle rustling and banditry in previously peaceful areas. Just this morning, my brothers informed me that some of our family’s cattle was stolen in Taraba State, and the gang kidnapped six of the herders. So it’s already starting to happen.

Despite the fact that it’s a very small minority of Fulani involved in criminality, non-Fulani Nigerians have lost trust in the Fulani. But there’s a real lack of understanding of what is going on in northern rural areas, and there are no effective government policies or interventions which separate out the criminal elements amongst the Fulani from the majority that are peaceful. So if things keep going the way they are, mistrust of pastoralists will grow even further.

What we observed from the research in Adamawa – as well as the XCEPT research we did in early 2022 in Bauchi, Gombe and Jigawa states – is the pressures of the massive population increases that are occurring in the north of the country. Farmers need more land to meet demand, whilst pastoralist communities continue growing and need land for grazing; so there’s a clash of interest between these two communities. On top of this, land grabbing further reduces land availability.

Environmental protection has also suffered. Traditionally, there was a culture of respect towards nature. Now large-scale farming clears forests and woodland to make way for cultivation, which has degraded the grasses and trees needed for grazing, and increased desertification. All of this means a large number of pastoralists are leaving Nigeria to go to Cameroon because the conditions in Nigeria are no longer conducive for their livelihood. Future fieldwork in Cameroon will help us understand the consequences of this.

Our previous research in Yobe and Borno states in Nigeria looked at these issues. We found that the Shekau faction of Boko Haram has been extremely predatory towards pastoralist communities in their areas of operation: attacking camps, rustling cattle, kidnapping and killing people. Even last year, my uncle was a direct victim of Shekau – his cattle were stolen and the herder he had hired to rear the animals was killed. Boko Haram attacks resulted in large-scale displacements of pastoralists southwards into Adamawa and Taraba, but also across to Cameroon and as far as Central African Republic. But recently the Shekau faction has been greatly weakened as a result of internal splits and military pressure, so we’re seeing pastoralists return – to a certain extent – to areas that would have been no-go a few years back.

ISWAP, which operates near Lake Chad, is largely tolerant of pastoralist communities, so long as they pay their zakat (tax) to the group. Our XCEPT research will take us to Maiduguri in Borno State to gain an updated understanding of the ongoing insurgency and its impact on pastoralist movement.

I think this kind of research can be really helpful. What we realise is that most of the information that people base their opinions and actions on in northern Nigeria isn’t based on what is happening at the grassroots. This has hardened attitudes towards pastoralists and Fulani people, and made it harder for those trying to take action to be effective.

We’ve seen examples of peacebuilding initiatives which show promise, but often the people leading them don’t grasp the local realities of pastoralism. In the next three or four years, pastoralism may become impossible.

Politically, pastoralists suffer from a lack of genuine representation. In effect, there are two levels of Fulani: the ‘town’ Fulanis, who have political influence, and those who are rural, largely nomadic, pastoralists. At the state and federal levels, Fulanis are actually quite well represented, but crucially these people aren’t pastoralists, and there’s a wide gap between them and rural pastoral communities. A lack of education for pastoralists reinforces this, with very few managing to get into positions of influence.

So this research is building a base of knowledge which can assist those who really want to create better responses to the challenges in these regions. We’re gaining access to local-level perspectives which need to be shared with people at the state, federal and international level, but also locally, to help to build confidence and dialogue within communities so that their livelihoods can be protected and they can co-exist more peacefully.

Top photo: Pastoralists at home on Jereende Pampo, a small island on the River Benue, Yola North LGA, Adamawa State, Nigeria. Recently arrived migrant farmers are trying to take over the island for cultivation, reducing the space for grazing there. Conciliation Resources/XCEPT researcher Abdullahi Umar Eggi is furthest to the right.

In 2022, populations across the world have reeled from a global cost of living crisis. Children in low and middle income countries are going to bed hungry, while for some families, drops in income will wipe out the equivalent of household healthcare budgets. By some estimates, 71 million people could fall into poverty.

African populations have borne some of the greatest hardships of crises taking place both near and far. While attention has rightly been on war between Russia and Ukraine, local and regional conflict has long undermined economic development across almost a third of the African continent. Local and regional conflict compounds (and is sometimes caused by) other supply constraints rooted in climate change and poor infrastructure, particularly in the agricultural sector.

This matters because struggles to eat, go to work, and save for the future threaten political stability and could create further violent conflict, which would accelerate economic decline. In Europe, fuel price hikes have already stoked social unrest. While some governments are spending big to protect citizens through tax reductions, wage increases, and price subsidies, others will have few tools at their disposal. Instead, their populations will be forced to adapt, changing patterns of work, consumption, and trade.

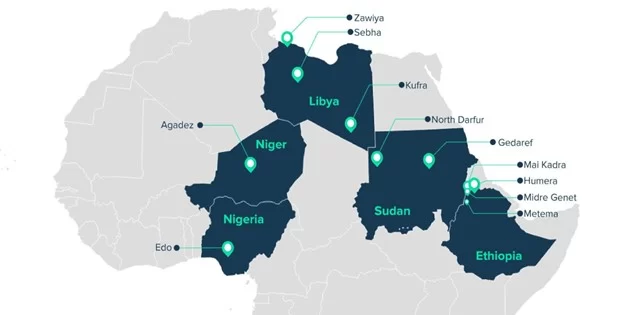

Research for XCEPT by Emani sought to understand this at a local level. In March and April 2022, in the immediate aftermath of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, we spoke to over 3,000 people across 11 locations in Ethiopia, Libya, Niger, Nigeria, and Sudan (Figure 1) – all of which import wheat from Russia or Ukraine.

The research zoomed in on the local effects of this conflict and the unique ways in which these effects interact with local dynamics. It compared the current situation with local challenges over the last decade, wider patterns of economic marginalisation, and the agency of residents – how are they coping with these challenges? What are the local effects of government policies? And what are the wider implications for stability in the region?

Here are five of our key takeaways.

1. Food and fuel prices have climbed fast

We asked survey respondents to tell us how much they were paying for staple foods ‘now’ (April 2022). Then we asked them to compare current prices with their experiences of spikes in price since 2010. Consumers were suffering particularly where imported products were popular. For example, Algerian milk was being sold in Agadez for nearly five times more in 2022 than 2010. A 25kg bag of rice cost 62% more in Agadez compared with 2011, and a ‘rubber’ (4kg bag) of rice in Oredo (Nigeria) cost 69% more. Some of the increases, however, were recent and sudden. In Sebha and Zawiya (Libya), flour was up 22% and 33% respectively in April compared to the beginning of 2022.

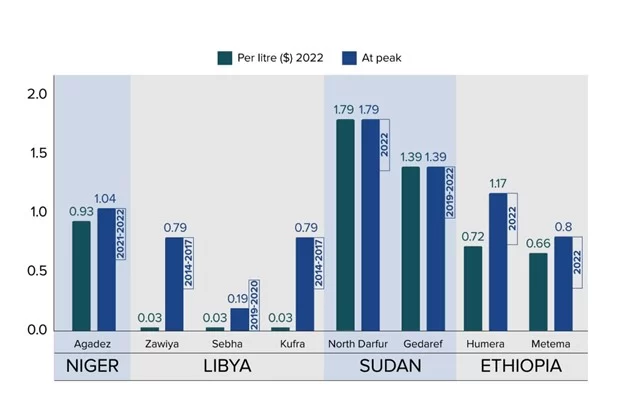

In some places, we asked about motor fuel too. Fuel prices in locations in Ethiopia, Sudan, and Niger were at their 12-year peak at the time of data collection (Figure 2).

2. Conflict, COVID-19, and currency values drove price fluctuations

Conflict is one of the main drivers of fuel prices in Libya. Libyans usually enjoy relatively cheap, subsidised fuel at around $0.03 per litre. As a result, when subsidised fuel becomes scarce, the rates set by the market are much higher than elsewhere. For example, for the three years after the outbreak of the Libyan civil war in 2014, the average fuel prices in Zawiya and Kufra skyrocketed to $0.79, 26 times the typical price.

In the areas we studied, the real, on-the-ground issue that shaped trade – and, by extension, prices – was the ability to move goods. Insecurity in Libya made driving goods down from the northern ports to Sebha (and onwards to Agadez) more expensive, with drivers asking higher fees and militia groups demanding unofficial taxes.

The availability of space for goods in southward-moving vehicles may also have been affected by policies designed to disrupt organised crime. A clamp-down on the smuggling of migrants from Agadez (Niger) through Sebha (Libya) reduced the number of vehicles travelling north with passengers and, correspondingly, the number of vehicles returning south with space to carry goods. Interviewees told us that this made it more expensive to move goods from Libya to Niger.

The unpredictable security environment had similar effects in Ethiopia and Sudan. The outbreak of the conflict in Tigray, northern Ethiopia, in late 2020 led to closures along the border. Towns on either side of the border, such as Gallabat in Sudan and Metema in Ethiopia, were cut off from one another. These towns had previously benefitted from joint trading agreements allowing for free cross-border movement during market days. The impact has been an increase in cross-border smuggling and in the cost of basic goods. For example, residents of Mai Kadra, on the Ethiopian side of the border, noted the price of vegetables and cereals rising as a result of supply shortages caused by blockades at Sudanese border crossings.

Onions per kilo [have gone] from 5 birr to 40 birr, tomatoes per kilo [have gone] from 4 birr to 40 birr… The main reason for this is the war and the resulting blockade of trade through the border crossings at Lugdi, Hamdayit and Medebay [district] … and the general national level shortage of supplies.

Interviewee in Mai Kadra

[Since] the blockage of the border some of the [businesses] are not performing well and some of the labourers are [laid-off] … There is very [little] merchandise imported from the border.

Survey respondent, Metema

In addition to conflict, a second key factor driving price fluctuations was the cost of foreign currency and reliance on – or desire for – imported goods, including basic food items such as pasta, flour and rice. For example, the COVID-induced closure of the Niger-Algeria border strongly impacted the price of pasta – widely consumed in Agadez and almost exclusively imported from Algeria.

With the exception of the pegged and stable West African Franc, people told us that wild variations in the value of the Naira, Libyan Dinar, Sudanese Pound, and Ethiopian Birr severely hampered their ability to pay for foreign goods. Other reasons were poor infrastructure, mismanagement of public resources and funds (Kufra), interruption in fuel subsidies (Sudan), and a ban on imported goods (Nigeria).

The closure of the Algerian border had a significant impact, especially on the price of wheat flour.

Representative of local government business centre, Agadez

3. Self-reliance offers some protection against price spikes

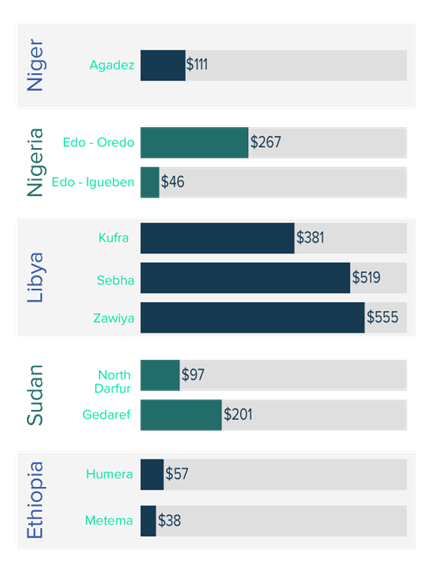

Monthly incomes vary considerably across the locations we studied (Figure 3). Yet the pain consumers are feeling does not necessarily correspond to their purchasing power. In rural Edo State (Nigeria), where the average income is only $46 per month, respondents were much less likely to notice spikes in food prices than in other areas we studied. Almost all Nigerians purchase at least some of their food, but those who rely on subsistence farming seem to be somewhat protected from market volatility.

Economic hardship may be driving deeper change in social and economic relations at the micro level. We found that residents of Oredo in Benin City (Edo State, Nigeria) were increasingly spending weekends in their ancestral villages to grow the vegetables they could no longer afford to buy on the market. This is despite the average income in peri-urban Oredo being nearly six times that of rural Igueben, a couple of hours drive away.

The only way I cope is visiting my home town to cultivate some of our own food and survive through that means.

Male, 25, in Oredo, Nigeria

Conversely, dependence on more expensive imported foods left some vulnerable to increases in price. For many, consumption of imported rice is a show of status – such that even local rice is sometimes packaged as having come from abroad in order to attract a premium. Nigeria’s ban on the import of most rice from abroad plus the more recent devastation of rice paddies in floods will drive prices up. Many households will feel noticeably poorer and have to change what they consume. At worst, they may struggle to put food on the table.

4. People are coping, some better than others

The situation appears most desperate in Kufra (Libya), where many respondents had stopped cooking hot meals to save on cooking gas – and some had reduced the number of meals they eat to save money on food, while taking on debt to make ends meet. Respondents in Sebha (Libya) were eating less meat and baking more at home. Across our Libya research sites, respondents reported switching to low-cost food brands. Facebook groups were important in helping residents to find good deals.

In Gedaref (Sudan), farmers were switching from sorghum, millet and wheat to more profitable cotton and maize production. This will decrease domestic food production and potentially exacerbate food insecurity in the region. People in Ethiopia, Niger and Nigeria described substituting cooking gas for wood, even though many were aware of the damage this could do to the environment – from deforestation in Edo State (Nigeria) and in Tigray (Ethiopia) to desertification in Agadez (Niger).

We are dependent on the electricity supply when there is no gas [and when it’s not available] we can sometimes cook just once per week.

Interviewee in Sebha, Libya

Sometimes we have to use wood to prepare food, and I walk long distances because of the lack of time to get gas for the car.

Interviewee in Kufra, Libya

5. Crime thrives in the absence of the state

In most locations, the state regulated and often subsidised the sale of both staple foods and fuel. In Kufra (Libya), with the lowest average income of the three areas studied in Libya, most respondents were receiving subsidies for food (82%) and medicine (76%). Government support was otherwise quite limited in scale and reach. Participants in Edo (Nigeria) mostly said support was negligible. The same was true for Gedaref and North Darfur (Sudan). Respondents in Mai Kadra (Ethiopia) said that government support had collapsed following the outbreak of conflict in 2020.

When the state cannot provide, people turn to other means and methods, which can further undermine the government’s ability to maintain the rule of law. Research participants in Metema (Ethiopia) told us about the importance of smuggling to bolster incomes. In Libya, subsidised goods were being appropriated by criminal groups and sold at high prices. In Sudan, the gap in officially sanctioned financial services is filled by unofficial money lenders and remitters.

Most local people have livelihoods strongly linked with contraband and smuggling … the smuggling is the source of non-food items such as soap, cloths, and related [goods].

Focus group participant, Metema, Ethiopia

Cooking gas is officially 5 dinars and is sold in the black market for 35-90 Dinar ($7.42 – $19.09).

Interviewee in Sebha, Libya

Peace through economic wellbeing

Even if the geopolitical and public health issues that have throttled food and fuel supply chains are resolved soon, people will continue to struggle. Among other repercussions, the scarcity of affordable goods on formal markets will drive the growth in informal trade, which will undermine state revenues and so the capacity of governments to provide services, in turn leading to a lack of public faith in the government. Declining tax revenues, popular discontent, and illicit financial flows are a potent mix in the Sahel, Horn of Africa, and Libya, where state authority is often already in question.

It’s not the first time that the countries we were researching – and others in Africa – have faced being locked into a vicious cycle of conflict and constrained economic growth. Economic growth rates are as much as 2.5 percentage points lower in countries affected by conflict, and the longer the conflict lasts the more those countries fall behind. And just as conflict constrains growth, prosperity can boost peace.

Yet as others have pointed out before, responses to conflict on the continent tend to focus on security, with the licit economy often collateral to measures aiming to disrupt illegal trade and armed groups. Instead, prioritising the licit flow of goods in critical cross-border towns and provinces can improve wellbeing, a sense of local stability, and weaken incentives towards potentially destabilising activities, from appropriation and smuggling of subsidised goods, to the more nefarious trade in drugs and arms.

More than thirty years after some scholars wondered if the end of the Cold War might herald the end of war as we know it, humanity is fighting at least 27 armed conflicts, more than at any time since the Second World War.

Two billion people, one out of every four humans on Earth, live in a conflict zone. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in early 2022 drove the number of people displaced by fighting to over 100 million: the most since the United Nations began keeping records.

With violence worldwide worsening for a decade, the UK aid-funded Cross-Border Conflict Evidence, Policy and Trends (XCEPT) research programme has gathered a team of King’s College London (KCL) researchers from a diverse array of disciplines not often associated with war studies. The idea is to employ new tools, techniques and perspectives to answer some of the most complex questions surrounding the roots of human conflict, including: Why does one person turn to violence in response to a traumatic event and another to peace?

The study of armed conflict is as old as war itself, but the team at KCL are hoping to bring a new point of view to the field. While much of the scholarship has tended to view problems from a single perspective – with an economist investigating the financial interests of two warring nations, for example, or a political scientist exploring how cultural divisions and disenfranchisement lead to violence – the KCL team includes experts in such varied fields as epigenetics (the study of how behaviour and environment influence genetic expression), gender, memory, neuroscience, and trauma.

Researchers are employing techniques ranging from brain scans to storytelling to try and tell a fuller story of the causes of violent and peaceful behaviour, and perhaps even to begin triangulating a person’s life experience and very biology with their beliefs and actions.

What Brain Science Teaches Us About Radicalisation

Neuroscientist Nafees Hamid wanted to know how, precisely, did the chatty young man in skinny jeans and trainers come to be so taken with violent extremism? And just as importantly, might it be possible to change his mind?

Hamid rolled the 20-year-old into an MRI machine in Barcelona recently, as part of the first study to use brain scans in attempting to answer such questions. The good-natured would-be jihadist, who spoke repeatedly of his desire to travel to Syria and die for his cause, answered questions and played a video game as Hamid and his colleagues studied his brain activity. Searching for the neurobiological underpinnings of his radicalisation, the researchers were focused especially on regions of the brain that perform cost-benefit analyses and process social pressures.

Hamid and his colleagues have now examined the brains of over 70 men living in Spain, all “devoted actors”, in the parlance of some social scientists, due to the strength of their convictions, in this case to Islamic fundamentalist ideologies. He is interested in the development of so-called “sacred values,” convictions so cherished people are willing to fight and die for them, and whether those values might be altered again, rendered “non-sacred”.

Results from the first two studies indicate that the distress of being excluded from a social group, long known amongst sociologists and criminologists as a powerful motivator, can solidify formerly “non-sacred values” into potentially more volatile “sacred” ones.

As with other groups, however, even the radicalised “devoted actors” tended to reduce their commitment to violence if they believed it left them out of step with their peers, perhaps suggesting community as a tool for moderating extreme beliefs.

How Narratives and Memories Can Drive, Resolve, and Avoid Conflict

While much of Hamid’s recent work has focused on people sympathetic to violent groups, many of his colleagues are working with victims of violence – sometimes of violence committed by those very same groups – including refugees in Syria, Iraq, and South Sudan. All places that have been at war for years.

Narrowly-focused research efforts risk overlooking what happens just beyond the parameters of a study. A project might investigate the desire for revenge amongst people wounded in conflict, for example, but neglect those whose trauma is psychological.

To try and fill some of the gaps between disciplines, therefore, XCEPT researchers are turning to the age-old tradition of storytelling, asking refugees, combatants, survivors, and prisoners to share their experiences in their own words.

In order to understand the ideological and psychological journey many terrorists take, researcher Rajan Basra has turned to an institution that’s been at the heart of countless political movements: prison.

From Marxism in Latin America during the 20th Century, to Loyalism and Republicanism in Ireland during The Troubles, to Islamic jihad in Iraq in the 2000s, ideologies of every sort have been shaped and spread by prisoners. Some then go on to plan, or carry out, insurgencies, revolutions, and terror attacks.

But if prisons have long served as centrepieces of propaganda, and recruiting stations for ideologues, they’ve also been a place where many extremists have had a change of heart. Basra is gathering stories from former inmates – people either accused or convicted of extremist and terror charges in Lebanon – to learn more about how they chose their paths. He hopes his work will offer everyone from peacekeepers to policymakers a more complete picture of how people come to choose violence or peace, as well as practical strategies for breaking cycles of violence.

Tracing Conflict’s and Peacebuilding’s Impact on People Over Time

The evolution of war over the past century, from primarily conflicts between nation states, to civil wars, insurgencies, terror attacks, and other non-state violence, is the primary reason that, even today, casualty rates are a fraction of what they were during the wars of the early 20th century. Those same developments, however, have meant that contemporary wars often involve more parties with more competing claims, and tend to last longer.

Between them, Iraq, South Sudan, and Syria are home to hundreds of thousands of combatants, and millions more people traumatised by fighting and displacement. This is why XCEPT’s KCL researchers have chosen the three countries for one of their most ambitious projects: the Impact of Trauma Survey.

The Impact of Trauma Survey is designed to examine relationships between violence, trauma, mental health, and social cohesion: a little-studied nexus that researchers hope will reveal clues about how the effects of war often lead to further violence. Researchers will employ surveys across the conflict zones, and then speak again with participants after they have received counselling and other mental health interventions. The aim of the project is to study how therapy, as well as changes on the ground — renewed fighting, for example, or an extended period of peace — can influence such things as a desire for revenge or reconciliation. The team at KCL hope to use this research as a base from which to propose psychosocial interventions which could help to reduce violence and promote peace.

New insights from a new approach

The KCL team has begun publishing its new research on the XCEPT website, and, along with the programme’s other partners, laying out its vision for an interdisciplinary future in conflict studies that includes new kinds of scholarship from a broader variety of fields.

In an effort to probe several under-explored topics in conflict research, XCEPT plans in the coming years to meld the KCL team’s work with a variety of analyses, as well as with new research that other programme partners are conducting now – topics that include the dynamics of cross-border conflicts and how they impact people living in borderlands.

If the ultimate goal of conflict studies is to end armed conflict, the past decade has made it clear once more that there is work to be done. The researchers at XCEPT and KCL are hoping new approaches might lead to a greater understanding of how people come to choose violence or peace.

The most recent work of the King’s College London team of XCEPT researchers can be found here:

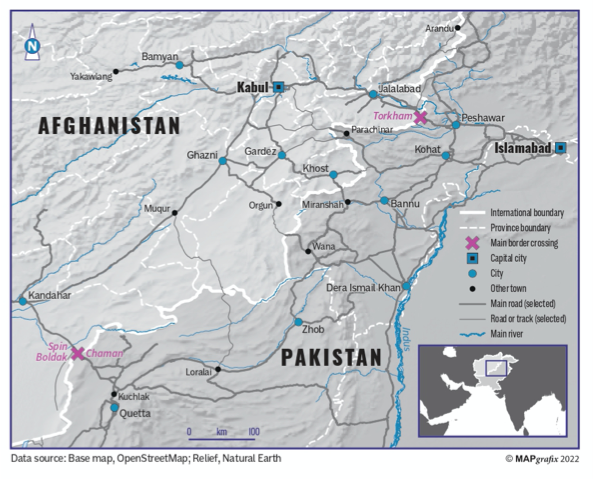

Over decades of conflict and instability, the border town of Torkham, one of the main crossing points between Afghanistan and Pakistan, has found a way to endure and to profit. Even as the Taliban swept across Afghanistan in August of last year, seizing major roads and border crossings on their way to Kabul, Torkham was closed to traffic for just hours. Despite the chaos in Afghanistan, state agencies and chambers of commerce in both countries worked together to ensure that cross-border trade through this vital gateway would continue.

Conflicts in border areas are prevalent across South and Southeast Asia, and they are some of the most challenging environments to navigate, owing to both their remoteness from the centers of national political power and the clash of local, national, and regional interests. Borders are where the competing interests of neighboring states collide, but they remain highly dependent on the cooperative flow of trade and the movement of people, creating inevitable tensions.

How these tensions can descend into violent conflict, and the durability of border towns like Torkham, are the focus of, Border Towns, Markets, and Conflict, a new report from the XCEPT programme. The report examines the unique dynamics at work in six border towns within some of the most intractable conflicts in Asia, the Middle East, and Africa. While these regional conflicts are notorious for their levels of violence and the suffering of the local populations, these border towns highlight the complexity of modern conflicts and the role that continuing cross-border trade can play in providing a modicum of stability.

Borders are about control and security, but also about flows and movement, creating a paradox for governance of conflict-affected regions. Over the past five years, Pakistan has sought to stabilize its border with Afghanistan through a series of overlapping security and governance initiatives. Responding to high levels of militancy and the cross-border flow of weapons and contraband, it has pursued an aggressive counterterrorism strategy while also garrisoning border gates, expanding customs and immigration facilities, and fencing almost all of the 2,600km Afghanistan-Pakistan border.

At the same time, Islamabad has strengthened its rule over its border regions, folding the erstwhile Federally Administered Tribal Areas into the province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, and replacing customary practices with state-run governance and judicial systems. Altogether these efforts have shown some success in improving regional governance and security, but the instability that followed the Taliban’s takeover in August has contributed to an increase in violence in the past 12 months.

These dynamics are covered in detail by Azeema Cheema, director of research and strategy at Verso Consulting in Pakistan, in the opening chapter of the new report. While writing about the changing security and trade environment at Torkham, she also highlights the uneven and often negative effects on local communities of Pakistan’s efforts to secure and formalize trade along its border.

In Pakistan and many other cases, national policies threaten local communities in volatile border areas. Expanded border infrastructure, the closing of border bazaars, and limitations on the free movement of laborers across the border damage local livelihoods, leading to clashes with the government and protests over compensation. Afghan communities that rely on cross-border mobility for job opportunities, healthcare, education, and family visits on the Pakistani side of the border have been hit particularly hard.

These effects add up to a set of enduring grievances with Islamabad, and feature in the narratives of militant groups who continue to resist the expansion of state control. The paradox, then, is that while Pakistan’s security efforts have sought to stabilize its border, in many areas they have produced the opposite outcome, and are leading in the longer term to an increased risk of instability and violence.

Similar trends are observable along the Myanmar-Thailand border in the town of Shwe Kokko, featured in the final chapter of the report, where a new commercial development consisting of a hotel and casino complex is being built in the jungle by the Karen Border Guard Force (BGF), a local militia group that is a key ally of the Myanmar army. In an area that has experienced decades of conflict, a long-running, informal pact has allowed the army to extend its control over locally contested territory while offering the BGF nearly free rein on illicit economic activity, including gambling and smuggling.

While this arrangement benefits armed elites, author Naw Betty Han highlights the marginalization and violence experienced by local populations—a situation that has deteriorated since the military takeover in February 2021 with growing allegations of human trafficking and sexual exploitation. At the same time, the BGF has been at the frontlines of the new cycle of conflict, fighting alongside the Myanmar army against prodemocracy armed groups based in the border area.

Situations like those in Torkham and Shwe Kokko, where trade, conflict, and state intervention interact, can also be found in the report’s other four chapters, which cover Makha in Yemen; Sarmada, Syria; and Maiwut and the Northern Bahr el-Ghazal region in South Sudan. Together they point to the complexity of conflict-affected border regions and the perverse effects on local populations caught in the middle.

One highlight of the report is that it champions the voices of local populations: seven of the eight authors are nationals of the countries they write about, and all six case studies involve on-the-ground research and insights. Working with local researchers is a core component of the project, and the report emphasizes the importance of this approach for building a more complete understanding of the causes and consequences of conflict. Engaging local residents, who live in and intimately understand these conflict zones, is an essential strategy for achieving equitable development in conflict-affected border areas.

This podcast and article was originally published on The Asia Foundation’s website.

Introduction

While many observers claim that Iraq’s Tishreen protest movement has been coerced into silence, I believe it maintains mobilisation momentum beyond street demonstrations. This is because the movement roots itself in storytelling; as a result, its relived memories of mass protests continue to motivate a collective consciousness.

Storytelling as a Tool

Storytelling helps to transform lived experience into meaning through the recounting of narrative via verbal and/or physical enactment and its reception by an engaged listener or audience. Therefore, storytelling is inherently a sociocultural process where people engage with the narrated story. Specific to time and place, this process also produces discourses in which people come to understand themselves. This subjectivity is central to storytelling; voice is always present. Storytellers engage in reflexive narration while provoking reflexivity in their engaged audience. Through this process, we construct our identities, find purpose and reimagine the past. Storytelling is a means to relay personal and collective experiences and collective aspirations, and to work towards them. For it to be utilitarian, instructive and a catalyst for change, storytelling must be intimately connected with and directly accessible to audiences and tap into their emotions. During protest movements, which are cauldrons of emotion at the boil, storytelling is a powerful tool to rouse solidarity and challenge the status quo.

Against the backdrop of asymmetric power relations, storytelling both generates positive relationships within communities and intensifies social cleavages, perpetuating divisive rhetoric and systemic violence. By distinguishing between destructive and constructive storytelling, we can delineate narratives that provoke and warrant acts of resistance. According to Jessica Senehi, constructive storytelling “is inclusive and fosters collaborative power and mutual recognition; creates opportunities for openness, dialogue, and insight; a means to bring issues to consciousness; and a means of resistance”. In contrast, destructive storytelling is “associated with coercive power (‘power over’ rather than ‘power with’), exclusionary practices, a lack of mutual recognition, dishonesty, and a lack of awareness. It’s a form of storytelling which sustains mistrust and denial.” Destructive storytelling arises when people break between the ideal and real in the erasure and/or whitewashing of stories. Distinguishing between destructive and constructive storytelling recognises coercive power versus shared power, dehumanization versus mutual recognition, dishonesty and unawareness versus honesty and a critical consciousness, and resistance and agency versus passivity and hopelessness. Iraq’s Tishreen movement has been a site of such dynamics, where citizens with agency use storytelling as a tool of resistance.

Tishreen: The Story

In October 2019, Iraq’s Tishreen movement (October in Arabic is ‘Tishreen’) emerged as a spring of collective consciousness. In the most expansive protests in Iraq’s recent history, Iraqis demonstrated for their rights and self-agency, which have been denied for decades. Thousands of protesters filled public squares and blocked roads in several cities. They gathered in places such as Baghdad’s Tahrir Square and Nasiriyah’s Habbouby Square where monuments tell stories of the country’s rebellious past against colonialism. Joined by academics, professional unions and guilds, the protesters shared stories of collective fury towards a corrupt, undemocratic and that institutionalises ethno-sectarian discrimination under the guise of representation. Through chants, poetry, music and art, the protesters shared their stories of alienation from a system that also alienates them from each other through sectarian policies and violence. Recognising that unfair elections recycle the same political players, they proposed demands that included the resignation of government, a redrafting of electoral law, the repeal of elitist, exclusive policies, the dissolution of parliament and early elections. Bringing together people from varied ages and socioeconomic groups, protests gave Iraqis a newfound sense of unity and solidarity. Post-secondary students provided the backbone for the movement. Women were prominently involved. The most widespread slogans in Iraq and the diaspora were نازل_آخذ_حقّي (“I’m taking back my rights”) andنريد_وطن (“We want a homeland”).

Feeling threatened, political parties and paramilitaries attempted to divide protesters by embedding armed undercover agents in protests who would kill security forces and/or protesters to incite violence. Besides live ammunition and rubber bullets, state forces fired tear gas canisters directly at protesters, killing many. Gruesome videos of dead protesters with tear gas grenades embedded in their skulls circulated on the Internet. Within months, riot police and paramilitary snipers killed over seven hundred protesters and injured over twenty-thousand, permanently handicapping dozens. Numbers have continued to rise since and, as of March 2021, some 1,035 protesters were reported killed and 26,300 injured. In the Kurdish Region of Iraq, Kurdish security forces killed at least six protesters and arrested 400 in December 2020. The government and paramilitaries weaponised enforced disappearances to weaken protesters, activists and journalists. An estimated 7,663 people have gone missing in the past three years. Besides physical violence, symbolic violence and hate speech have been common. State and non-state actors waged a psychological war involving sound-flash bombs to terrorise protesters and a social media war with character assassinations to silence them. Engaging in destructive storytelling, Iran-backed paramilitaries created Telegram channels and hashtag factories to attack activists and protesters, labelling them as “jokers” and falsely accusing them of being foreign agents. Vicious and persistent hate speech campaigns targeted Iraqi activists both online and offline, aiming to delegitimise them and the movement and to incite assassinations. Meanwhile, the government enforced Internet blackouts to silence protesters who grew more resourceful and persistent. Radios placed in public squares warned those participating in sit-ins of armed threats. Activists in the Kurdish Region unaffected by the blackout worked to fill the information gap and reported human rights violations. Despite and because of the consistent attempts to silence them, Iraqis want to be heard and seen.

The paramilitaries created a culture of fear. Coupled with the impact of the coronavirus pandemic, the protest movement was forced to a halt, with many observers claiming the Tishreen movement was crushed. However, the movement remains alive in the collective consciousness of Iraqis and through other forms of .

Memory & Continued Mobilisation

Realising the lengths to which the government and paramilitaries will go to promote fear and silence protesters’ narratives, activists see the power of their storytelling. As Iraqis in the country and in the diaspora continue to discuss online their memories from the protests’ early days, these stories help to maintain the movement’s momentum. Social media outlets emerging from the movement have kept the protest alive through commemorations of important dates, events and persons. In particular, fallen protesters are celebrated on the anniversaries of their murders and massacres at Nasiriyah’s Zeitoun Bridge, Baghdad’s Sinak Square and Najaf’s Sadrain Square are commemorated. With the revisiting of these stories, calls for accountability continue and several campaigns have emerged. With hashtags and slogans asking #من_قتلني؟ (“Who killed me?”), Iraqis demand transparent investigations and prosecutions of those responsible for assassinations. #End_Impunity is a hashtag that has developed into an organisation that launches targeted campaigns against corrupt officials and members of security forces responsible for violence against civilians. Online awareness campaigns challenge unjust draft laws, such as the Combatting Cybercrimes Bill, The Freedom of Assembly and Peaceful Demonstrations Bill and dangerous proposed amendments to the Personal Status Law. انقذوا_الأيزيديات_المختطفات# (“Save Kidnapped Yazidi Women”) connects the cause to the wider Tishreen movement and blames state institutions for failing to respond to Islamic State’s attempted genocide and the sexual slavery of Yazidi women. Activists recognise the direct connection between memory, storytelling and activism to keep the movement alive in public consciousness. This is notable in the explosion of the Iraq arts scene. Murals at Tahrir Square and elsewhere remind the public not only of mass political protests but also of the potential for further grassroots mobilisation and self-expression.

Conclusion

Storytelling in Iraq’s Tishreen movement reminds us that memory, both an outcome and part of storytelling, is an indirect expansion of power. It helps to reclaim identities, histories and resistance movements. Owning the narrative around the protests has maintained the Tishreen movement’s momentum through other forms of other grassroots mobilisation. State institutions and paramilitaries’ attempts to erase collective memory will fail, as resilient and determined youth now believe in the power of public pressure and taunt them with defiance: إنت منو؟ (“who are you?”).

This article was originally published on the International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation’s website.

The modernization policies in Saudi Arabia supervised by Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman have brought about a number of transformations in the structure of state institutions and Saudi society. One of the foremost domains in which change has been visible is religion. It is common to hear that the kingdom’s political-religious system was built on an alliance between the ruling Al Saud family and Wahhabi Salafism. However, Prince Mohammed appears to be moving away from this approach, as he seeks to mobilize the youth by reducing the religious and social constraints imposed as a result of that alliance.

These transformations raise an important question about Saudi ties with Salafism, a branch of Sunni groups that defines Islam as anything the prophet Muhammad said or did and that was upheld by his first three generations of his followers, which Saudi Arabia helped to spread over recent decades. Support for Salafism was one of the instruments of soft power that the kingdom used to expand its influence in Muslim societies. One place where this happened is Yemen. In 1982, Muqbil al-Wadi’i, a Salafi scholar who had been residing in Saudi Arabia, established Dar al-Hadith in the northern governorate of Saada. This is seen as the starting point for the Salafi movement in the country. By backing Wadi’i, the Saudis sought a counterweight to the Zaydi Shia community in Saada, leading members of which supported Iran’s revolution of 1979.

Saudi Arabia benefited from the Salafi expansion in Yemen. The Salafis’ discourse portrayed Saudi Arabia as the primary protector of Islam, and Salafi teachings were largely based on the ideas of Saudi Salafi scholars such as Abdel-Aziz bin Baz, Mohammed bin al-Uthaymeen, Mohammed bin Ibrahim Al al-Sheikh, and other figures. Subsequently, the religious divide in Yemen was driven by transnational ideas, with the Saudis influencing the Salafis and Iran influencing the Zaydis, a situation that later fueled the ongoing Yemeni civil war.

Given their ideological differences with the Iran-backed Houthis, Salafi groups have become a significant force supported by the Saudi-led Arab coalition.

While Salafism appears to be reducing in importance within the Saudi state, the kingdom has reinforced its alliance with Salafis in Yemen, even expanding cooperation in some areas as conflict rages on. Given their ideological differences with the Iran-backed Houthis, Salafi groups have become a significant force supported by the Saudi-led Arab coalition. Several military brigades dominated by Salafis were able to alter the balance of power on vital military fronts. For example, the Salafi Giants Brigades, which are supported by both Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, spearheaded the operations to control Yemen’s western coastal areas in 2017 and 2018. They again made major gains in the more recent battle for Shabwa.

The changing relationship between the Saudi state and Salafis in Saudi Arabia has been accompanied by transformations in the Salafi environment in Yemen. Traditionally, Yemeni Salafis are divided into three categories: Salafi-jihadis; political Salafis, who have Salafi roots but follow the path of political Islamist movements by involving themselves in politics, such as Al Rashad Union Party and the Peace and Development Party; and traditional Salafis, which encompasses most Yemeni Salafis. While the traditional Salafi schools have historically abstained from engaging in politics, prioritizing obedience to the ruler (wali al-amr), this principle was shaken by the Houthi takeover of the Yemeni capital, Sana’a, in 2014. The Salafis woke up to the fact that the Zaydi Houthis, whom they opposed, had become the dominant military force in Yemen.

This change in the political context prompted many followers of traditional Salafism to reconsider their quietist principles, as they found themselves at the center of a war effort, leading armed groups. Alongside Mohammed bin Salman’s transformations in Saudi Arabia, this reconsideration led to a new relationship between the two Salafi communities—one centered on Saudi support for Salafis who were engaged in a political conflict, not simply spreading their religious doctrine.

Saudi Arabi has three fundamental motives for strengthening its ties with Yemeni Salafi groups. First, there is deep enmity between Salafis and the Houthis, whom Saudi Arabia is also fighting. The clash between the Salafis and Houthis is not only one over doctrine, but also has a military dimension. In 2014, the Houthis took over the Saada-based Dammaj Center, the first Salafi school in Yemen, and forced the Salafi community to leave the area. The sense of grievance among Salafis was revived when the Houthis expanded into other areas in which Salafis were present. When the Saudi-led coalition began its military operations in March 2015, the Salafis proved to be reliable partners in the coalition’s ground operations.

A second motive is that the Salafis have no specific political agenda. Their primary aim is to combat the Houthis, based on a religious rationale, particularly after the takeover of the Dammaj Center and the expulsion of Salafis from Saada. This gave the Salafis pride of place among other Yemeni groups that were fighting alongside the coalition, including the Islah Party and southern separatists, who have political agendas that conflict with those of the Saudi-led coalition.

A third motive is to maintain Saudi religious influence in Yemen, which Salafi groups have helped to sustain in the past four decades, and to prevent Salafis from engaging in any compromises with the Houthis. To the Saudis, the agreements that some Salafi leaders signed with the Houthis in areas of northern Yemen in 2014 were alarming. These called for peaceful coexistence, an end to hostile rhetoric, and direct communications between the sides to deal with any issues. The kingdom is providing the Salafis with military and financial support, and at the same time is continuing to fund their religious centers. Although the Yemen conflict has impaired educational institutions in Yemen, Salafi schools continue to operate and are even expanding in several parts in the country, including Aden, Dhaleh, and Mahra.

For the Salafis, having regional backers, such as Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, is important. Receiving financial support is only part of the reason. The Salafis also seek some sort of legitimacy in their fight against the Houthis, especially after concerns emerged about ties between the traditional Salafis and Al-Qaeda groups. Fighting under the Saudi-led coalition has helped to water down such apprehensions, not least because Salafis have joined the Yemeni government. Indeed, the eight-member Presidential Leadership Council, the executive body of the internationally recognized government, includes the Salafi leader Abu Zara’a al-Mahrami, who is also the leader of the Giants Brigades.

Considering the political and military context in Yemen, the relationship between Saudi Arabia and Salafis there will remain strong, despite the religious changes inside the kingdom. While Saudi Arabia pursues its battle in Yemen, Salafis will remain their preferred partners and a key part of the kingdom’s network of influence in the country. The role of the Saudi-backed Salafi groups in Yemen has been shifting over the past years. While it was a soft power spread through religious teaching till last decade, Salafism today is becoming a part of Saudi hard power, transforming its students into fighters on the battlefield. This is not only the case in Yemen, but also in other areas such as Libya, where the Saudi-backed Madkhali Salafi groups witnessed similar transformation. The case of the Salafi groups underscores the complex evolution of cross-border exchange of religious ideas, with external powers able to grow influence amongst local communities.