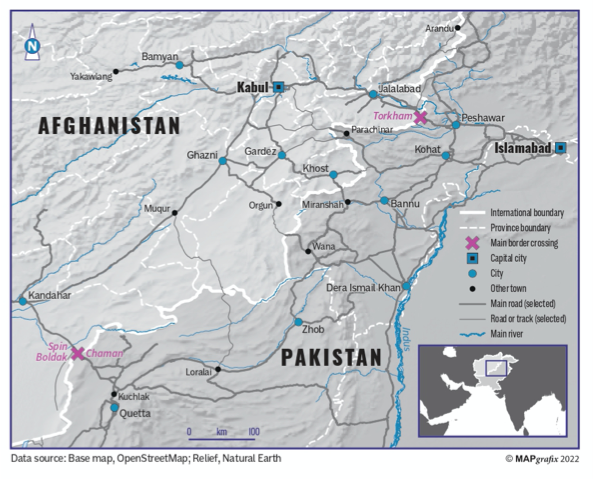

Over decades of conflict and instability, the border town of Torkham, one of the main crossing points between Afghanistan and Pakistan, has found a way to endure and to profit. Even as the Taliban swept across Afghanistan in August of last year, seizing major roads and border crossings on their way to Kabul, Torkham was closed to traffic for just hours. Despite the chaos in Afghanistan, state agencies and chambers of commerce in both countries worked together to ensure that cross-border trade through this vital gateway would continue.

Conflicts in border areas are prevalent across South and Southeast Asia, and they are some of the most challenging environments to navigate, owing to both their remoteness from the centers of national political power and the clash of local, national, and regional interests. Borders are where the competing interests of neighboring states collide, but they remain highly dependent on the cooperative flow of trade and the movement of people, creating inevitable tensions.

How these tensions can descend into violent conflict, and the durability of border towns like Torkham, are the focus of, Border Towns, Markets, and Conflict, a new report from the XCEPT programme. The report examines the unique dynamics at work in six border towns within some of the most intractable conflicts in Asia, the Middle East, and Africa. While these regional conflicts are notorious for their levels of violence and the suffering of the local populations, these border towns highlight the complexity of modern conflicts and the role that continuing cross-border trade can play in providing a modicum of stability.

Borders are about control and security, but also about flows and movement, creating a paradox for governance of conflict-affected regions. Over the past five years, Pakistan has sought to stabilize its border with Afghanistan through a series of overlapping security and governance initiatives. Responding to high levels of militancy and the cross-border flow of weapons and contraband, it has pursued an aggressive counterterrorism strategy while also garrisoning border gates, expanding customs and immigration facilities, and fencing almost all of the 2,600km Afghanistan-Pakistan border.

At the same time, Islamabad has strengthened its rule over its border regions, folding the erstwhile Federally Administered Tribal Areas into the province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, and replacing customary practices with state-run governance and judicial systems. Altogether these efforts have shown some success in improving regional governance and security, but the instability that followed the Taliban’s takeover in August has contributed to an increase in violence in the past 12 months.

These dynamics are covered in detail by Azeema Cheema, director of research and strategy at Verso Consulting in Pakistan, in the opening chapter of the new report. While writing about the changing security and trade environment at Torkham, she also highlights the uneven and often negative effects on local communities of Pakistan’s efforts to secure and formalize trade along its border.

In Pakistan and many other cases, national policies threaten local communities in volatile border areas. Expanded border infrastructure, the closing of border bazaars, and limitations on the free movement of laborers across the border damage local livelihoods, leading to clashes with the government and protests over compensation. Afghan communities that rely on cross-border mobility for job opportunities, healthcare, education, and family visits on the Pakistani side of the border have been hit particularly hard.

These effects add up to a set of enduring grievances with Islamabad, and feature in the narratives of militant groups who continue to resist the expansion of state control. The paradox, then, is that while Pakistan’s security efforts have sought to stabilize its border, in many areas they have produced the opposite outcome, and are leading in the longer term to an increased risk of instability and violence.

Similar trends are observable along the Myanmar-Thailand border in the town of Shwe Kokko, featured in the final chapter of the report, where a new commercial development consisting of a hotel and casino complex is being built in the jungle by the Karen Border Guard Force (BGF), a local militia group that is a key ally of the Myanmar army. In an area that has experienced decades of conflict, a long-running, informal pact has allowed the army to extend its control over locally contested territory while offering the BGF nearly free rein on illicit economic activity, including gambling and smuggling.

While this arrangement benefits armed elites, author Naw Betty Han highlights the marginalization and violence experienced by local populations—a situation that has deteriorated since the military takeover in February 2021 with growing allegations of human trafficking and sexual exploitation. At the same time, the BGF has been at the frontlines of the new cycle of conflict, fighting alongside the Myanmar army against prodemocracy armed groups based in the border area.

Situations like those in Torkham and Shwe Kokko, where trade, conflict, and state intervention interact, can also be found in the report’s other four chapters, which cover Makha in Yemen; Sarmada, Syria; and Maiwut and the Northern Bahr el-Ghazal region in South Sudan. Together they point to the complexity of conflict-affected border regions and the perverse effects on local populations caught in the middle.

One highlight of the report is that it champions the voices of local populations: seven of the eight authors are nationals of the countries they write about, and all six case studies involve on-the-ground research and insights. Working with local researchers is a core component of the project, and the report emphasizes the importance of this approach for building a more complete understanding of the causes and consequences of conflict. Engaging local residents, who live in and intimately understand these conflict zones, is an essential strategy for achieving equitable development in conflict-affected border areas.

This podcast and article was originally published on The Asia Foundation’s website.