Uganda, a model for refugee management?

Uganda is widely cited as a model country for the hospitality and integration of refugees having implemented an open-door policy and refugee self-reliance approaches since 1999.1 Currently, Uganda has the world’s third-largest refugee population, with over 1.7 million refugees, the majority of whom are women, mainly from South Sudan, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and other countries such as Rwanda, Burundi, Somalia, Sudan, and Eritrea as of December 2024.2 Once in Uganda, refugees are allocated land in settlements for shelter, but also farming to get food for home consumption or to earn an income. In the spirit of self-reliance, refuges access public services such as health care, education, water, and land with host communities.

Refugee Welfare Committees (RWC) as a forum for participation

In line with its often praised progressive approach and open-door policy for refugees, Uganda has established a refugee-led leadership structure known as Refugee Welfare Committees (RWCs) in all refugee settlements, including Nakivale and Oruchinga, to ensure that refugees participate in community programs and critical decisions that shape their lives. These committees, based on the Refugee Act of 2006,3 operate on three levels: RWCI (clusters), RWCII (zones/villages), and RWCIII (entire settlement). Elections are held every two years. RWCs are the formal representative body for refugees, ensuring protection and access to justice. RWCs are the first point of contact for issues and communicate with the Office of the Prime Minister (OPM), UNHCR, local authorities, aid agencies, and host communities. Each RWC level runs a committee with various secretariats for sectors such as finance, health, and education. Originally intended to foster relations between refugees and nationals, RWCs in Uganda have become crucial for enhancing service delivery, community organization, identity, and political participation among refugees.

Challenges to women’s participation in decision-making

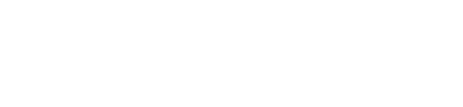

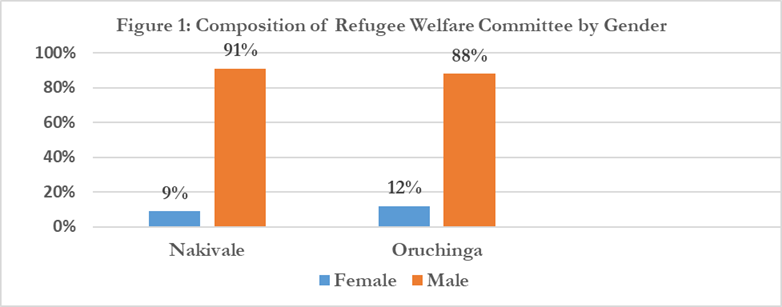

While the formation of RWCs in Uganda aims to promote inclusive leadership, it does so without addressing systemic gender challenges to participation in decision-making processes. The RWC guidelines assume that women and men are able to compete on the same footing for elective positions. This assumption is far from reality given the socio-cultural challenges faced by women. Research carried out in Nakivale and Oruchinga refugee settlements located in Southwest Uganda in April 2024 showed the limited involvement of women in RWCs (see Figure 1). Despite limited participation, women’s participation is still perceived as important (see Figure 2).

Explanations for the low representation of women in RWCs fall into institutional, cultural, and individual factors. Institutional factors are largely related to the gender-neutral legal framework of the RWC, which does not explicitly encourage women’s participation; for example, there are no gender quotas or monitoring mechanisms to ensure women’s participation. In addition, social and cultural factors – such as gender stereotypes and socially ascribed roles that make women responsible for children, the elderly, and domestic work – hinder women’s participation. As a result, women are often overburdened and do not have time to fully engage in decision-making processes. Women and girls face challenges related to harmful practices such as early and/or forced marriage, and unequal access to, or control over, services and resources. Girls are often pushed to drop out of school and help with household chores. Sexual gender-based violence and reproductive health-related factors including rape, sex slavery, and forced pregnancy, lower their self-esteem and confidence to participate in public life. Systemic institutional and cultural challenges lead to significant gender disparities in property ownership and greatly hinder women’s participation. These challenges particularly affect women’s education, especially their literacy skills, which are essential for leadership roles. Consequently, women are often at a disadvantage compared to their male counterparts. A female refugee observed, “If a girl is not in school, she is expected to get married, regardless of age.” Another noted, “Being a woman is restrictive enough, and when you add being a refugee, [it] is a double tragedy” (KII and FGDs).

Women at the frontlines of water and land conflicts

Since water and food provision are among the roles socially ascribed to women, they are often at the risk of water and land conflicts. Women engage in water collection for household use. Water collection can be arduous: travel to and from water sources, and waiting in queues, can take hours, and the distance is often covered on foot. They are exposed to conflict risks: verbal and physical fights are not unknown at water collection points.

Women also engage in subsistence farming and firewood collection – these resource generation and gathering activities can come with the same risks as water collection.

Empowering women in land and water management

Over half of all refugees are women and girls, yet their voices are visibly missing in decision-making on the affairs that affect their day-to-day lives. Lack of women’s participation in water and land decision-making negatively impacts their daily lives by perpetuating gender inequalities and stereotypes, hindering access to resources, and limiting their ability to shape water and land related policies and laws that directly affect them. This short-coming is critical considering women’s involvement adds value to resource management, results from the research suggest that the gender of the household head has the highest positive effect on household water provision, with more female-headed households paying water user fees than male-headed households. The presence of women in RWCs also increases the information flow and awareness among women in the larger settlement. Women leaders experience challenges at home and community and therefore understand the unique challenges other women experience daily (KII, Nakivale). The importance of women’s participation is further underscored by evidence that women tend to be better custodians of water and better land use managers, precisely due to their socially ascribed roles and dependence on these resources.

A way forward

Since women are most affected by land and water conflicts, and have a higher stake in water provision and household food security, their voices need to be heard in decision-making. Gender-responsive and inclusive management policies should be implemented as a step towards social cohesion, better resource use, and improved service delivery. Leveraging women’s participation in refugee leadership broadens their horizons, enabling them to support themselves and their communities. It ensures that services and policies are informed by women’s voices and experiences, aligns humanitarian efforts with gender-specific needs, and equips women with skills for future reintegration into their home countries or relocation to new ones.

Hence, there is a need to deliberately use affirmative action, including quotas, to support women’s involvement. Therefore, gender-responsive and inclusive guidelines, such as clearly defined quotas in RWCs, are crucial to facilitate women’s participation. The majority are refugees are women, who are better understood and advocated for by women leaders who share their daily experiences. Moreover, there is evidence that having more women in decision-making positions increases the level of public sector effectiveness and accountability.4 This is particularly relevant in Uganda as the country seeks to enable and encourage refugee self-governance.

- Mwangu A. R. 2022. An assessment of economic and environmental impacts of refugees in Nakivale, Uganda, Migration and Development, 11:3, 433-449, DOI: 10.1080/21632324.2020.1787105 ↩︎

- UNHCR 2025 Global Appeal. https://reporting.unhcr.org/global-appeal-2025-executive-summary ↩︎

- The Refugee Act 2006. http://www.judiciary.go.ug/files/downloads/Act%20No.%2021of%202006%20Refugees%20Act2006.pdf ↩︎

- Naiga R, Penker M, and Hogl K. (2017). “Women’s Crucial Role in Collective Operation and Maintenance of Drinking Water Infrastructure in Rural Uganda.” Society & Natural Resources 30(4). p. 506-520. ↩︎